Originally posted at Public Sector Inc.

By Steve Malanga.

In my Wall St. Journal piece this weekend I discussed how the IRS is holding up municipalities’ efforts to move workers into new, less expensive pension systems, even when employees via their union agree they’d like to make the move. I spent most of the piece on the IRS issues, but it’s worth exploring why places like San Jose and Orange County think that some workers might voluntarily agree to take less in pension promises. Let’s look at some math.

Orange County, for instance, gained approval in 2009 from its main union to begin offering new workers and current employees already in its defined benefit pension system the option to switch to a new hybrid plan that features a smaller DB plan combined with a 401(k) style savings.

County government was hoping to persuade employees to move away from its very expensive defined benefit plan, which offers county employees 2.7 percent at age 55 (that is a pension equal to 2.7 percent of final salary times the number of years worked, starting at age 55). In other words, under the county’s current plan, if you go to work at age 25 and retire at 55 from county government, you walk away with 81 percent of your final salary as a pension. Most folks in the private sector would consider that rich, indeed.

Still, though much of the burden for paying for this system is with the taxpayer, county employees must contribute toward their own retirement, too. Under the current 2.7 percent at 55 rate, that contribution amounts to 10.51 percent of pay.

The DB component of the county’s new hybrid plan, by contrast, offers workers 1.62 percent at 65. In addition, the plan includes a defined contribution savings account into which an employee can contribute additional money (tax free right now of course), and the county will match those contributions up to 2 percent of base salary.

Why would anyone accept a plan like this? Well, for one thing, it costs a lot less. The contribution rate for the employee portion of the DB plan is 6.94 percent of pay. For an employee earning $60,000 a year, the additional take-home pay amounts to $90 every two weeks, or $2,340 per year, according to the county’s data. Not chickenfeed.

Still, more take-home pay isn’t the only incentive. County officials believe that younger employees in particular would like the option of a more portable plan (here’s where the DC portion comes in) because they don’t plan on working for the county forever. They might also relish more take home pay because they don’t particularly think the idea of working to age 65 to qualify for retirement, like the rest of us, is so bad. (Actually, Social Security retirement age is rising on a sliding scale and is 67 or 68 for most of us still working.)

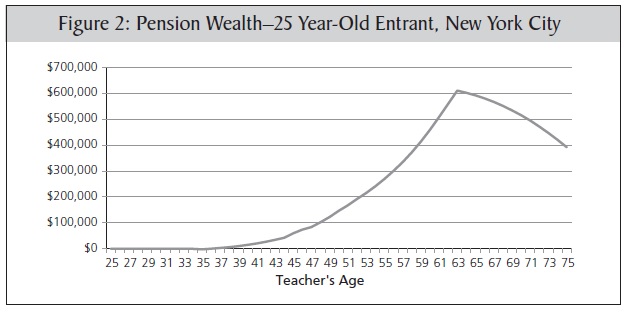

This actually makes a lot of sense. One of the infrequently discussed shortcomings of many of the government DB plans in effect now is that they save very little for workers in their first 10-to-15 years employed by government, and then these plans ramp up the savings during the final years of someone’s long government employment.

If a worker leaves even after 10 years employed at such a job, he gets sometimes much less in retirement savings to take away than if he were part of a defined contribution plan where employee and employer contributions are more evenly dispersed. Far more people, moreover, leave government employment before reaching full retirement than we think.

This Manhattan Institute study, for instance, looked at figures for teachers in 10 big school systems nationwide. Only 28 percent of teachers stayed in the systems for 20 years or more. Those who left before got a raw deal when it came to retirement benefits, thanks to the current method of funding DB plans (see chart below for the way pension wealth accrues for teachers in NYC). As the study observes:

Under the traditional defined benefit (DB) pension system that currently covers 89 percent of public-school teachers nationwide, teachers accrue very little retirement wealth through the early and middle portions of their careers. Then, toward the end of their working lives, they receive steep increases in retirement wealth as they near the system’s retirement eligibility thresholds. Teachers who change systems or leave the profession before these late-career increases are left with relatively little retirement wealth. For the minority of teachers who stay in place and thus qualify for full benefits, DB pension systems offer relatively high maximum retirement earnings. But they do this by relying on significant teacher turnover, which lets these plans leverage contributions made on behalf of the majority of teachers to subsidize the retirements of a select few.

These plans have obvious benefits for governments, too, beyond the savings. As I’ve written before, more than two dozen states have restrictions against changing worker pensions, even for work not yet done. That makes it impossible to save any money by altering pensions for current workers. But when workers choose a new system themselves because they think it will benefit them, those restrictions generally don’t apply. As Orange County Supervisor Moorlach says in the piece I link above, it’s a way of getting savings without a face-off with unions and a collision in court.

And there is some growing evidence that government employees want choices like this. A poll by the Manhattan Institute’s Empire Center found that 70 percent of New York teachers said they would have considered a defined contribution plan if one had been offered at the time of their initial employment.