By Amber Manfree.

In the historic heart of Napa Valley, a moderate climate and the alluvial soils deposited by the Napa River create perfect conditions for world-class cabernets. An acre of vines here sells for around $300,000, or 25 times the state average for irrigated cropland.

Yet a group of landowners have ripped out 20 acres of these prized vineyards to make room for river restoration, with levee setbacks, terraced banks and native plants.

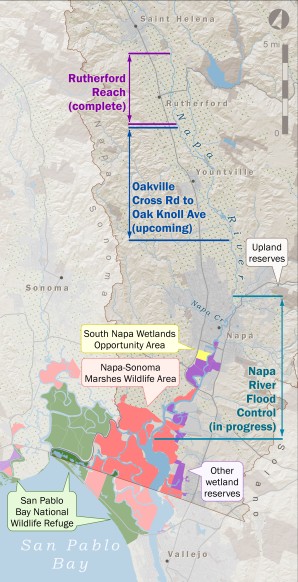

The project runs the length of Rutherford Reach, a 4.5-mile stretch of the Napa River between St. Helena and Oakville. Landowners say the changes will bring economic benefits over the long term by reducing crop losses from floods and plant disease. Most of all, they feel good about giving back to the river that has brought them so much.

Rutherford Reach is one several sites undergoing major habitat and flood control improvements on the Napa River. Some projects started more than 40 years ago. Others are just getting off the ground.

Far from postage-stamp restorations, these efforts are steadily transforming a huge swath of wetlands in a very lived-in area, re-establishing geomorphic function at the landscape scale.

Innovative funding, inclusive planning and adaptive management power these projects and offer lessons for river restoration elsewhere.

Here’s a closer look at three major flood control and river rejuvenation projects on the Napa: Rutherford Reach, downtown Napa and the lower Napa River:

Rutherford Reach: a landowner-initiated restoration

For decades, landowners along the Rutherford Reach struggled with bank instability and floods. The river was confined to create more space for vineyards while upstream dams reduced sediment delivery, leading to incision and eventually lowering the riverbed six to nine feet.

Without a healthy stream profile, desirable river processes and species were lost. Invasive plants such as giant reed and Himalayan blackberry overtook the banks, further degrading habitat and hosting problem insects.

Then, in 2002, a group of influential vintners organized as the Rutherford Dust Society approached Napa County about partnering to restore the reach, and a new path to restoration unfolded. The landowners:

- Led the initiative and were involved throughout the planning process

- Are making meaningful contributions of land and money

- While motivated in part by economic considerations, they find conservation to be its own reward

More than two dozen landowners support the $20 million restoration and its long-term maintenance, each paying an annual fee based on the linear feet of river crossing their property. Altogether, the landowners will contribute about $2 million over 20 years. The project also is supported with $12 million from a county bond measure and $7.7 million in state and federal grants.

County partnership gives landowners better control over the spread of Pierce’s disease, a grapevine-damaging bacterium spread by sharpshooter insects, said Jeremy Sarrow, a specialist with the Napa County Flood Control and Water Conservation District.

The county can accommodate landowner requests for removal of riverside plants that host the disease, an action requiring a state Department of Fish and Wildlife permit. The agency generally does not grant these river modification permits to private landowners. Also, the State Water Resources Control Board requires landowners in this reach to show how their land management controls the amount of fine sediment entering the river, and participating in restoration can earn them a waiver.

Importantly, the landowner funding supports long-term monitoring of restoration, with any excess rolled into an interest-bearing fund for unexpected maintenance costs.

County staff have spent 10 years monitoring the transition from degraded to restored riparian corridor, revising techniques as they go. If something isn’t working – invasive weeds are popping up, a log jam blocks fish passage, an herbicide kills non-target species – the corrections can be made in the field, and landscape processes continue in the intended direction instead of backsliding.

With the first 4.5 miles of riparian corridor construction wrapping up, project managers are preparing to restore 9 more miles just downstream between Oakville Cross Road and Oak Knoll (See map). Together, these projects will transform habitat along 25 percent of the river’s 55 miles.

Downtown Napa: Redesigned flood control revitalizes city core

At least 22 serious floods have inundated Napa since 1865, which means locals have been sandbagging their doorways once every seven years or so since the town was on the map. These days, a revolutionary flood control project is reshaping the city center.

In the mid-1990s, the community rebuffed an Army Corps proposal to dredge, straighten and armor the banks of the Napa River. Stakeholder disagreement and funding gaps had hindered flood control throughout the 1900s, but this time things were different.

Residents insisted on a design that improves the environment and makes the river a focal point of downtown. Agencies responded by assembling a community coalition of many residents, local nonprofits, the Army Corps and county flood control officials. The group engaged in a lengthy planning effort and developed a “living river” design. The plan was to accommodate both floods and the environment by removing armored banks and reconnecting the river to its historical floodplain.

Fifteen years later, 7 miles of the downtown reach have been transformed both visually and functionally.

The confluence of Napa Creek and the Napa River has been extensively reshaped, providing space for floodwaters and improved conveyance. Native plants such as tules, alders and willows stabilize banks.

Meticulously engineered placement of woody debris has made the streams more hospitable for salmon and steelhead trout. Napa Creek overflow channels as wide as boxcars are buried under streets.

Seven bridges and two railroad trestles have been reconstructed at higher levels and dozens of buildings have been torn out to make way for the river.

Capacity-increasing overflow basins and the enormous Oxbow bypass look and function like parks when water is at normal levels. The parks, which connect to riverside walking and biking trails, are used for community events year round.

In all, planners estimate they have tripled the river’s capacity while improving habitat and bolstering the local economy. The Army Corps views the effort as a pilot project for flood-prone communities.

The lower Napa: steady, strategic land acquisitions for conservation

At the mouth of the Napa River, a vast wetland complex has quietly become the second-largest tidal restoration project in California, after the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project near San Jose. The reserve system grew steadily over the past 40 years, eventually encompassing more than 35,000 acres of wetlands encircling San Pablo Bay.

San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge, one of the oldest of the reserves, now spans more than 10,000 acres near the mouths of the Napa River and Sonoma Creek. Building on this foundation, the Land Trust of Napa County along with county and state agencies have strung together properties along 12 miles of the Napa River to extend the reserve system north from Mare Island to Napa. Today, this network provides habitat, recreation and increased flood capacity.

In addition, tidal flows are returning and marshes are renewing themselves across 13,000 acres of former salt evaporation ponds and hayfields on the north shore of San Pablo Bay, now part of the state-managed Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area.

The South Napa Wetlands Opportunity Area, 1,200-acre component of the flood control project, ties the downtown improvements with the downstream string of estuarine wetland reserves. Breached and lowered levees give floodwaters a safe place to spread out, increasing flood capacity and conveyance downtown and reconnecting the river to its floodplain and tidal marsh.

Both habitat and geomorphic function are being restored throughout the lower Napa River. With every additional levee breach, the area is increasingly hydrologically connected to the San Pablo Bay region.

Rejuvenating a sense of place

Each of these restoration efforts was driven by communities with a strong sense of place and an appreciation of the environment, along with a practical need for flood control and a societal imperative to bring back the salmon.

With the completion of ongoing projects, tens of thousands of acres and about 60 percent of the Napa River’s length will feature improved habitat, intact geomorphic function and reconnected floodplains.

With experience gained through adaptive management, project managers are increasingly skilled in restoring landscape processes. The accrued knowledge will be an asset to future work.

Residents await the next big flood with a new attitude, less afraid and more curious to see how well the redesign will perform. The Federal Emergency Management Agency is revising flood risk zones to reflect improvements, which will lower insurance rates for many.

Years of field surveys will be needed to assess restoration project outcomes for the river’s other residents: the birds, fishes and mammals. Judging by appearances, habitat is already much more appealing to wildlife.

Pond turtles, ducks, geese, and egrets are common within a few steps of First and Main streets in downtown Napa. Beavers have recolonized surprisingly fast, felling newly planted cottonwoods and building dams at the Rutherford Reach and even on Napa Creekjust off Main Street.

The definitive test will be what happens with native salmon and steelhead, as hopes for their return have guided much of the habitat restoration.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at California Water Blog.

Amber Manfree, a native of Napa County, is a geographer and postdoctoral researcher with the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. She co-edited the 2014 book, “Suisun Marsh: Ecological History and Possible Futures.”