A leading advocate of the view that public pensions are alarmingly underfunded thinks rising costs could, in the next five to ten years, push some cities into bankruptcy and some states into insolvency.

Joshua Rauh, a Stanford University finance professor, said in a new studyissued by the Hoover Institution that 564 state and local pensions systems reported a “net pension liability” of $1.2 trillion under new government accounting rules.

But Rauh believes the debt is nearly three times larger, $3.4 trillion, because the pension systems, even under the new rules, use an overly optimistic annual earnings forecast, 7.4 percent, for investments often expected to pay two-thirds of future pensions.

Rauh used a 3 percent risk-free Treasury bond rate. That not only follows the basic principles of finance, he said, but is more realistic given low interest rates, the failure of pension funding levels to recover after a major bull market, and other factors.

“More and more money is going to have to go into these funds, and you are going to see more and more bankruptcies along the likes of Detroit, San Bernardino, Stockton, California,” Rauh told CNBC last week. “And over a five- to ten-year horizon, I would expect there to be a number — many, many more cities going bankrupt and many states that are insolvent.”

Most state and local governments in the nationwide study contribute 7.5 percent of their revenue to pensions, Rauh’s study concluded, but need to contribute 17.5 percent to keep pension liabilities from rising.

“Even contributions of this magnitude would not begin to pay down the trillions of dollars of unfunded legacy liabilities,” he said. None of the “50 worst cities” listed in the study, ranked by additional contributions needed to prevent more debt, are in California.

An oncoming wave of bankruptcies may be an extreme view, not to mention a 3 percent long-term earnings forecast. But a Citigroup study last month shares Rauh’s view that exposing “hidden” pension debt is a first step toward public pension reform.

Citigroup estimates that the total unfunded government pension liabilities for 20 industrialized countries is a “staggering $78 trillion,” nearly double the $44 trillion they have reported.

“Making these contingent liabilities more clear or complete is the first step towards further pension reform to address the increased risks from a rising dependency ratio (retirees vs. active workers) and a rising cost burden of public pension systems,” said Citigroup.

Last week, a state Senate committee rejected a bill requiring the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office to create an internet website listing major state debt, including pensions and retiree health care, that also would be shown on a page in the ballot pamphlet.

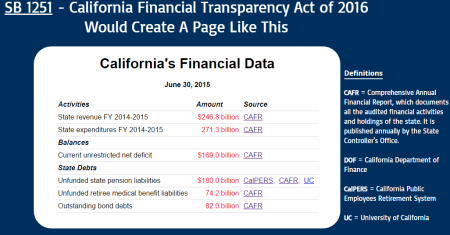

State Sen. John Moorlach, R-Costa Mesa, said his “California Financial Transparency Act” (SB 1251) would give voters “basic reliable nonpartisan financial information” as they consider bonds, spending measures, and candidates.

Moorlach, an accountant and financial planner known for predicting that risky investments would lead to the Orange County bankruptcy in 1994,created a website to show what the basic financial information might look like.

The bill, rejected on a party-line vote, was opposed by public employee unions who argued that ballot measures have a nonpartisan financial analysis and that the broad debt numbers have no direct relation to ballot measures, lack context and might confuse voters.

Pension debt can seem distant, with most bills not due for decades, and unpredictable or even unknowable as the reported unfunded liability swings up and down with the stock market and the yield from huge investment funds.

The bite taken from employer budgets by annual contributions to the pension funds is less abstract. Some call it “crowd-out” as growing pension costs reduce the money available for basic government programs, services and personnel.

Stephen Eide of the Manhattan Institute issued a “California Crowd-Out”study last year that found, among other things, government staffing in December 2014 remained 8 percent below the December 2007 level, while private-sector jobs were 2.4 percent higher.

The “crowd-out” from pension and retiree health care costs was an issue as voters in San Diego and San Jose overwhelmingly approved cost-cutting pension reforms four years ago.

The ballot pamphlet argument in San Diego said Proposition B means more money for “fixing potholes and street repairs, maintaining infrastructure, restoring library hours, and re-opening park and recreation facilities.”

In San Jose, the ballot argument for Measure B said: “Retirement costs consume more than 20% of the general fund and are projected by independent actuaries to increase for years. This is unsustainable.”

With “spiking,” pension excess becomes even less abstract and gets a face. For example, an Orinda-Moraga fire chief, who retired in 2009 at age 50 with a pension much larger than his salary, told the Wall Street Journal he was a “poster child” for spiking but didn’t make the rules.

Last September, the Contra Costa pension board voted to reduce Peter Nowicki’s initial pension, $240,923 a year, to an amount, $172,818, that is below his final base pay, $193,281.

A review by a law firm found that Nowicki, with two contract amendments, inflated the final pay used to calculate his pension, mainly by cashing out unused vacation time with smaller amounts from holiday, terminal and retroactive base pay.

Manipulating final pay to improperly boost pensions is a common spiking method, surfacing sporadically in well-publicized incidents over the past half century. The two big state pension systems, CalPERS and CalSTRS, both have anti-spiking units.

Implied pension excess surfaces in several ways. The Los Angeles Times reported this month that at least 17 legislators including Moorlach are “double-dipping,” collecting their state salaries and a public pension from another government job or office.

The “$100,000 pension club” of retirees with big pensions was posted on the internet a decade ago by a reform group led by Marcia Fritz. Another group, Transparent California, now has a searchable database of state and local government pay and pensions.

“The main thing is to engage people when you talk about pensions, because it’s boring to people,” Fritz, president of the California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility said in 2011. “When we put the list up, it was the same reaction as ours — unbelievable.”

Whether through debt, crowd-out or excess, the public seems to have received a message about pensions from somewhere.

A statewide Public Policy Institute of California poll issued in January 2014 found that 85 percent of likely voters think the amount of money spent on public pensions is somewhat of a problem and 73 percent support switching new hires to a 401(k) plan.

[divider] [/divider]