By Jay Lund.

Sustainable use of groundwater in California will require major changes in groundwater management, use, and recharge. Under the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, groundwater basins as a whole are responsible for sustainability. But millions of people and thousands of governments and private land managers must recharge more water and pump less to achieve this goal, without disrupting existing surface water rights. How can responsibility and credit for groundwater use and recharge be developed and assessed without debilitating water wars?

State-overseen accounting already civilizes common disputes involving land ownership, money, gasoline, electricity, and weights and measures generally. Local water utilities measure and estimate water quantities to improve accountability, transparency, and management for their own customers, regulators, system managers, and financiers. Some groundwater basins, such as Orange County, Santa Clara Valley, and some adjudicated groundwater basins have rudimentary accounting systems to assess fees for groundwater pumping, plan for recharge, or limit pumping. But California overall lacks a strong unified system of water accounting, particularly for groundwater.

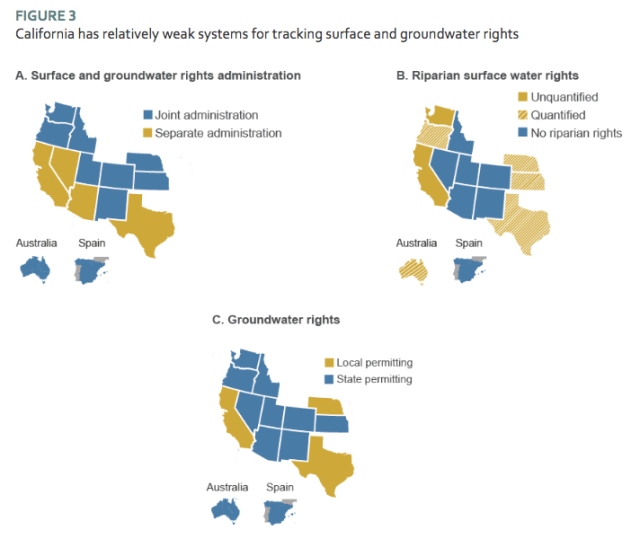

California should join other advanced economies in dry regions and institute a formal water accounting system. Australia, Spain, Colorado, Texas, and other western states already have stronger and more unified water accounting systems. A report released last week by the Public Policy Institute of California, in collaboration with university researchers, details 12 lessons for water accounting in California and reviews water accounting in Australia, Spain, and 11 other western states. The accounting systems vary in their details, but all have a single authoritative accounting of water flows based on measurements and estimates of water availability, use, and flows returning to streams and aquifers after use.

Source: Escriva-Bou et al. 2016

For groundwater, stronger water accounting would transparently inform regulators, users, and the public alike on the balance of groundwater use and recharge and the responsibility and credit for pumping, recharge, and net pumping. Such accounting is needed to assess basin sustainability, assess liability for pumping and credit for recharge, as well as the natural flows of water underground into and between basins. Without such accounting, agreements, rights, and allocations regarding water are difficult to make and enforce, begetting excessive legal expenses and delays while basin management remains unsustainable. An accounting framework also makes detection and correction of errors more transparent and efficient.

A stronger state system for water accounting also would benefit the administration of surface water rights, environmental flows, water markets, and more integrated science-based management, which currently suffer from lack of a strong common state accounting system. The many partial water accounting systems maintained by separate state and local agencies and programs sometimes compound water disputes and weaken each other more than offering common ground to civilize disputes. A common water accounting system would help civilize and enlighten a host of chronic water conflicts, and provide a scientific basis for resolving many disputes.

How can California get to a stronger and more useful water accounting system? Australia, motivated by its great 12-year drought, took 10 years to revamp and solidify its water accounting. California might begin with an independently-led task force involving the major state agencies along with independent experts and stakeholders, commissioned to make recommendations to the Governor’s office and the legislature.

California is already paying most of the cost needed for a credible water accounting system. Major water utilities already measure or estimate their water sources and uses, usually in automated “supervisory control and data acquisition” (SCADA) systems. State forethought to organize and automate collection of these data would allow transparent, accountable, timely, and inexpensive incorporation of such existing data for water accounting. (Smaller users will take more time, but are less important overall.) The hardest part is organizing state agencies around a single coherent water accounting framework, which can be supported by locally-collected data and integrated with regional computer models.

Civilizing water conflicts begins with data and an accounting framework.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at CA Water Blog.

Jay Lund is a professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis.