Originally posted at CalPensions.

By Ed Mendel.

CalPERS made two court filings last month after the San Bernardino city council approved a confidential draft of a plan to exit bankruptcy, as if stepping up opposition in reaction to something in the plan.

But a spokeswoman for the big pension fund said the filings are unrelated to the city’s plan or “term sheet.” As directed by a federal bankruptcy judge, the plan is a starting point for closed-door mediation and has not been revealed to the public.

The two CalPERS court filings continue an all-out legal battle triggered when San Bernardino did the unprecedented: skipped employer pension contributions last fiscal year, running up a tab of about $17 million, before resuming payments in July.

The giant California Public Employees Retirement System wants its more than 3,000 local government employers to know that withholding pension contributions is a no-go zone, not an option if they struggle financially.

San Bernardino, in danger of not making payroll, made an emergency bankruptcy filing in August last year, staying debt collection. The city stopped about $30 million in various payments, roughly half owed to CalPERS.

In response, CalPERS became the lone opponent of San Bernardino’s eligibility for bankruptcy, unsuccessfully attempted to sue the city in state court, and accused the city of creating a crisis and withholding key financial information.

“I don’t believe anyone in this courtroom seriously thought the city was not insolvent,” U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Meredith Jury said while ruling San Bernardino eligible for bankruptcy last August.

Two weeks after the San Bernardino city council approved the term sheet last month CalPERS asked to appeal the eligibility ruling: “Never has a bankruptcy court set such a low bar for a municipal debtor to enter the doors of a bankruptcy court.”

And a week after that, CalPERS filed a brief in support of an appeal by the state Department of Finance and state Controller of the judge’s ruling on $15 million in city tax revenue.

The judge blocked a state attempt to withhold $15 million in sales and property taxes. San Bernardino had not returned a similar amount of unspent housing funds after the state shut down local redevelopment agencies.

“I’m just amazed at their decision to fight the city on land and sea and air, at every level,” Mayor Patrick Morris told the San Bernardino Sun after CalPERS filed the brief in support of the state appeal.

Without the $15 million, he said, “We can’t pay our employees. It sinks the ship — we can’t pay CalPERS. It’s legal idiocy.”

Judge Jury expressed similar puzzlement in August about CalPERS opposition to bankruptcy eligibility, saying the apparent alternative is dissolving the city. “How does that help CalPERS if the employees aren’t paid?” she said.

As deep-pocketed CalPERS tries to drive home the point that there is a stiff price to pay for skipping pension contributions, no legal tactic left untested, voters delivered another kind of message to politicians last week.

After 26 years as San Bernardino city attorney, James Penman, was recalled by 60 percent of the vote along with Councilwoman Wendy McCammack. Another recall target, Councilman John Valdivia, survived the challenge.

Penman twice ran against Morris for mayor and lost. The clash between factions led by Morris and Penman, said by his critics to be too close to labor, is often cited when the San Bernardino political culture is called “dysfunctional” or “toxic.”

Morris, who did not run for re-election, is one of the three Democratic mayors who joined San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed’s drive for a pension reform initiative opposed by a labor coalition. Penman was replaced by Gary Saenz.

McCammack was recalled by 58 percent of the vote (1,256) in her council ward. But she was the leader among 10 candidates for mayor (24 percent or 3,043 votes) and will be in a Feb. 5 runoff with Carey Davis, endorsed by Morris and the Sun.

Two weeks before the election, Councilman Robert Jenkins was charged with harassing an ex-boyfriend and Councilman Chas Kelley was charged with perjury about campaign funds. Kelley resigned. Jenkins was defeated last week by Benito Barrios.

What impact the outcome of the election might have on the course of the bankruptcy remains to be seen. One of the recent issues debated by the council is whether costs could be cut by contracting with another government agency for fire services.

Councilman Fred Shorett, now facing a runoff against Anthony Jones, made several unsuccessful attempts, backed by Morris, to get the city council to ask the city manager to solicit bids for city fire services.

At a council meeting Oct. 7, Penman said an earlier request found that providing police services through the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s department would cost more and put fewer officers on the street.

“This was especially true because the conversion factor from our pension system, the CalPERS system, to the county system for the sheriff would result in an adjustment we were going to have to pay of several million dollars,” Penman said. “The same would be true if we were to contract with San Bernardino County Fire.”

In a sketchy plan last fall for operating in bankruptcy, San Bernardino proposed a “fresh start” that would “reamortize CalPERS liability over 30 years,” perhaps in a way that would “realize value of $1.3 million per year starting fiscal year 2014.”

Among the unanswered questions now: Did the city make a more detailed or different proposal for cutting pension debt in the confidential term sheet last month? Will the election result in a new city direction on pension debt?

As was pointed out in the Stockton bankruptcy, CalPERS is only the manager of the city pension funds, a “conduit” or “pass-through” agency. The pension debt is owed to employees and retirees, who presumably would take the hit if the debt is reduced.

The latest valuation of the San Bernardino pension funds, as of June 30, 2011, shows employer contribution rates for this fiscal year that are not unusually high: safety (police and fire) 31.5 percent of pay and miscellaneous 18.2 percent of pay.

The funding levels are near the CalPERS norm. Using market value assets, the safety plan is 74 percent funded with a debt or “unfunded liability” of $152.6 million. Using actuarial value assets, safety is 83 percent funded with a debt of $99.7 million.

In the view of some, what makes San Bernardino unusual, though CalPERS apparently disagrees, is the ability to pay.

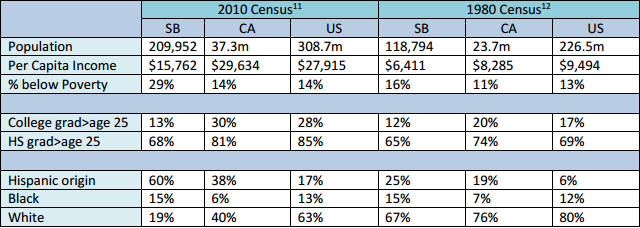

A George Mason University case study of the bankruptcy said San Bernardino is the “poorest city of it size in the state,” with nearly a third of the 210,000 residents below the national poverty line.

But the city charter automatically links pay for police and firefighters in San Bernardino, which has a median household income of $35,111, to 10 other cities that have an average median household income of $62,118.

In the last three decades, said the study, San Bernardino was bypassed by the I-15 Interstate and three major employers closed: Kaiser Steel, Santa Fe Rail Yard and Norton Air Force Base.

Three remaining large employers do not pay property taxes: CSU San Bernardino, San Bernardino Community College and San Bernardino County. State actions have shifted redevelopment funds and vehicle license fees.

“As an unfortunate consequence of politics and historical trends, the city found itself committed to salaries and pensions that were neither proportionate nor sustainable,” said the George Mason study by Frank Shafroth and Mike Lawson.