A federal judge last week set a hearing on approval of Stockton’s plan to exit bankruptcy for next March 5. But the hearing could turn into a multi-day trial if the city can’t cut a deal with the last holdout creditor, two Franklin bond funds.

The plan to cut Stockton debt would pay Franklin $95,000 for a $35 million bond issue. A Franklin attorney, calling the cut “unprecedented,” unsuccessfully argued that the city had not disclosed enough information about settlements with other creditors.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein, ruling disclosure was adequate, gave Stockton permission to circulate the debt-cutting “plan of adjustment” to all creditors for a vote on Feb. 10. An objection from one creditor can force a trial.

The apparent failure of a court-approved plan of adjustment to solve structural financial problems in Vallejo is raising questions about whether the Stockton plan also might fail to close a long-term budget gap.

As in Vallejo, the Stockton plan does not cut pension debt. A Franklin attorney said last week an objection to the Stockton plan might point to the uncut pension debt as an example of unfair treatment of creditors.

Stockton contends that the plan does indeed cut retiree debt, mainly through the elimination of retiree health care, which is a large and growing cost in the troubled Vallejo budget.

Voters approved a 1-cent sales tax increase as Vallejo emerged from a 3½-year bankruptcy in November 2011. Now two years later Vallejo has a $5.2 million general fund deficit in the current fiscal year, projected to grow to $8.9 million next year.

Last week, Vallejo was not mentioned during the Stockton hearing. But the judge said the Stockton 30-year plan should disclose the “renewal risk” of a ¾-cent sales tax, approved by city voters this month but due to expire in 10 years.

“If I thought there was going to have to be another Chapter 9 (bankruptcy) case in 10 years, I probably would not confirm the plan,” said Klein. “I’m not sure any judge would.”

Large debt owed the California Public Employees Retirement System has been an issue in three city bankruptcies triggered by revenue losses during the recession. Whether public pensions can be cut in bankruptcy has yet to be tested.

Vallejo officials considered cutting pension debt, then chose not to try after CalPERS threatened a costly legal battle. San Bernardino skipped payments to CalPERS last fiscal year, running up a tab of about $17 million before resuming payments.

Stockton does not want to cut pensions, arguing they are necessary to remain competitive in the job market, particularly for police. Two bond insurers backing major Stockton bond issues unsuccessfully opposed the city’s eligibility for bankruptcy.

Assured Guaranty (backing $164 million in bonds) and National Public Finance Guarantee ($89 million) contended, among other things, that Stockton’s initial “ask” treated them unfairly because the largest creditor, CalPERS, was untouched.

Judge Klein asked the Franklin attorney last week if he similarly had CalPERS “in the crosshairs.” Jim Johnston said Franklin had been focusing on disclosure issues, but “CalPERS very well may be implicated” in objections to the Stockton plan.

The Stockton attorney, Marc Levinson, said the city understands that if it cannot reach an agreement with Franklin, there will be litigation over confirmation of the exit plan.

“So, we would just as soon get that started right away,” Levinson said. A problem for Franklin is that the loan collateral, two golf courses and a park, have use restrictions and are not regarded as vital by the city.

Klein said he “clings to the hope” that the mediator in Stockton’s agreements with the two bond insurers, U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Elizabeth Perris, can “work her magic” in the Franklin dispute.

The Stockton plan said the city’s debt or “unfunded liability” for retiree health care in July 2010 was $544 million, far more than the CalPERS unfunded liability of $172 million. Eliminating retiree health care sharply reduced projected future costs.

(If Vallejo had ended retiree health care, the city might not have a $5.2 billion deficit this year. A general fund budget adopted in June spends $7.1 million on retiree health care and $14.2 million on payments to CalPERS.)

The Stockton plan also projects major future savings from several pension reforms. Employees agreed to pay their full share of CalPERS costs, 7 to 9 percent of pay, ending a “pickup” of the employee share by the city.

New employees will receive a lower pension formula with no retirement credit for sick leave or optional benefits. Pay cuts of up to 23 percent, including some “add-pays” for police, will reduce the salary on which pensions are based.

With state pension reforms that took effect Jan. 1, said the plan, new Stockton hires arguably have a 50 to 70 percent cut in pension and retiree health benefits with no Social Security from city employment.

Current Stockton employees lose an estimated 30 to 50 percent of their retirement benefits from the loss of retiree health care, paying the employee CalPERS share and the cuts in pay.

To forecast future CalPERS rates, Stockton used an actuarial firm, Segal, and a change in CalPERS actuarial methods approved in April. Stockton also assumed two changes discussed but not yet adopted by the CalPERS board:

Higher costs from improved mortality rates and demographics and lowering the current investment earnings-based discount rate used to offset future pension obligations, 7.5 percent a year, by an additional 0.25 percent.

“Who knows, let alone CalPERS, what’s going to happen in 10, 20, 30 years,” said Levinson, the Stockton attorney. A municipal bankruptcy plan covers 30 years, he said, unlike three-year plans in business and individual bankruptcies.

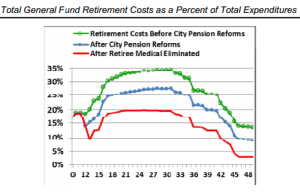

A chart in the Stockton plan shows that retirement costs are projected to be near 20 percent of the general fund for about a decade. That’s around the level that prompted San Diego and San Jose voters to approve cost-cutting pension reforms last year.

The Stockton plan projects that from fiscal 2012-13 to fiscal 30-31 retirement costs will average 18 percent of the general fund — nearly the same as before the reforms when the average was 17 percent from fiscal 2008-09 to fiscal 2011-12.

“The net result of these changes is that the general fund is not going to be overwhelmed by retirement costs,” said the Stockton plan.