Originally posted at CalPensions.

By Ed Mendel.

A pension reform initiative proposed by San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed and others got a mixed cost analysis last week from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, quickly trumpeted by opponents.

The measure would give state and local governments the option of cutting retirement benefits current workers earn in the future, while preserving benefits already earned through past service.

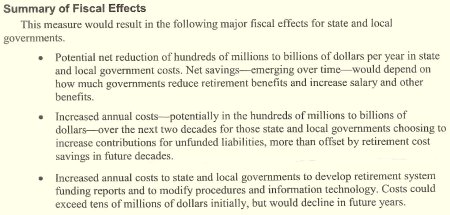

The analyst said this part of the initiative has the potential to reduce “hundreds of millions to billions of dollars per year in state and local government costs,” depending on how much retirement benefits are reduced and salary and other benefits are increased.

A lesser-known part of the initiative aims to strengthen retirement benefits by requiring governments to propose, but not enact, annual plans for fully funding pensions and retiree health care in an unusually short 15 years.

The analyst said annual costs could increase “hundreds of millions to billions” over the next two decades for governments “choosing to increase contributions for unfunded liabilities, more than offset by retirement cost savings in future decades.”

Ironically, the part of the initiative intended to strengthen not cut retirement benefits created an apparent weak spot attacked by the opposition, a coalition of public employee unions.

According to the analyst, said a coalition news release, “San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed’s proposed ballot measure to slash pension benefits for public employees could potentially cost state and local governments ‘billions of dollars.’”

Reed said in a news release that the opponents “fail to acknowledge that the LAO found that these potential increases would be more than offset by the potential savings from the initiative.”

The analysis co-signed by Gov. Brown’s Finance department was sent to state Attorney General Kamala Harris. Her office will write a brief title and summary for the initiative, which is all some voters are believed to read about a measure.

Last year, Dan Pellissier said California Pension Reform suspended an initiative drive “after determining the attorney general’s false and misleading title and summary makes it nearly impossible to pass.”

Reed has said he may poll on voter reaction to the initiative title and summary before deciding whether to proceed with a drive to gather the signatures needed to place the measure on the ballot.

A polling firm hired by the union coalition found that portraying the initiative as “eliminating” public employee pensions “fosters a visceral negative response from voters,” the Sacramento Bee reported last week.

Reed told the Bee the opponents have to “mischaracertize what we are doing.” He said the initiative does not propose “eliminating” public employee pensions. The poll-tested word was used in the coalition news release last week.

“It’s clear from this assessment that this poorly crafted measure will not only add to the retirement crisis in our state by eliminating vested retirement benefits for teachers, nurses, firefighters, school bus drivers and other public employees, but also cost our communities and state billions of dollars,” said Dave Low, chairman of Californians for Retirement Security. “This measure would be a financial disaster for taxpayers and retirees alike.”

Reed and the initiative advocates say if soaring retirement costs are eating up funds needed for basic services and programs, cutting pensions current workers earn in the future can quickly yield sizable savings.

That’s allowed in private-sector pensions and a dozen other states. But in California, courts are said to have ruled that the pension promised at hire becomes a “vested right,” which can’t be cut unless offset by a new benefit of comparable value.

Most attempts to cut retirement costs, including union bargaining and pension reform legislation last year (AB 340), increase employee pension contributions and give new hires lower pensions, yielding savings reformers say are too small and too slow.

In San Diego and San Jose, where retirement costs were taking 20 percent or more of city general funds, voters last year approved measures that, in different ways, attempt to cut pensions current workers earn in the future.

Vested rights were the key issue in a five-day trial last July for several union suits opposing the San Jose pension reform measure. A pending decision by Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Patricia Lucas is expected to be appealed by the losing side.

If the initiative proposed by Reed and others is placed on the ballot and approved by voters, the California Public Employees Retirement System is likely to launch a legal battle to preserve the current view of pension vested rights.

The initiative, a state constitutional amendment, would give new and current employees vested rights to pensions and retiree health care only for work they have already performed.

If a government employer declares a fiscal emergency, or finds that an underfunded plan is at risk of not being able to pay retirees, the initiative would allow retirement benefits earned after that point to be cut in several ways.

The analyst said a government employer could cut pensions and retiree health care, cut annual inflation adjustments, increase the retirement age, and require employees to pay a larger share of costs.

If the benefits are normally subject to labor bargaining, the employer must try to bargain changes. If negotiations, mediation and fact-finding fail to produce an agreement, the employer can use existing procedure to impose the change.

“In cases where these changes are not within the scope of collective bargaining, the government employer could implement the changes directly,” said the analyst.

The initiative requires government employers with pensions or retiree health care less than 80 percent funded to prepare a plan to reach full funding in 15 years, and then hold public hearings on status reports each year until the plan is fully funded.

Many CalPERS pensions plans are less than 80 percent funded. Much of the retiree health care promised state and local government employees is zero percent funded, pay-as-you-go each year with no money invested to cover future costs.

Moreover, most of the payments being made to reduce the debt or “unfunded liability” for promised pensions and retiree health care are based on reaching full funding in 30 years. Getting there in 15 years would require much larger payments.

So why give initiative opponents an opening to claim the measure could cost governments “billions,” if they choose to try to get to full funding in 15 years?

Reed has said 15 years is an estimate of the time the average worker will remain on the job. Some think retirement benefits should be paid while the worker is on the job, avoiding unfairly passing debt to future generations that did not receive the services.

And though it may not be a strong selling point, there also is the analyst’s view that increased annual costs in the short term would be more than offset by retirement cost savings in future decades.

“To the extent that some government employers increase employer and/or employee contributions in the near term to accelerate payment of pension and retiree health liabilities, those government employers could increase their retirement funds’ assets and investment returns and dramatically reduce the amount of employer contributions needed over the long term,” said the analyst’s report.