With a new twist, Stockton’s plan to leave a huge pension debt untouched was still an issue last week as the city council, hoping to end a two-year bankruptcy, approved settlements for 95 percent of the claims.

The settlements include Assured Guaranty and National Public Finance Guarantee, the main opponents of Stockton’s eligibility for bankruptcy. The bond insurers argued that an early plan to cut bond debt, but not pension debt, treated creditors unfairly.

Now the last major creditor that has not settled, Franklin Bonds, argues that if Stockton exits bankruptcy without cutting pension debt, the city could slide back toward insolvency like Vallejo.

A trial is scheduled May 12 if the city and Franklin do not reach an agreement. While Assured and National recover most if not all of their money under the exit plan, Franklin issued an unsecured loan and would receive $94,000 for a $37 million debt.

A Wall Street credit rating agency, Moody’s, said in February that without pension relief Vallejo, which emerged from bankruptcy in November 2011, and the two cities currently in bankruptcy, Stockton and San Bernardino, risk returning to insolvency.

Last month U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein said he hasseen news reports about Vallejo’s budget problems and wants to be sure that if Stockton exits bankruptcy without addressing pensions, the city will not face a second insolvency.

Not mentioning Vallejo, Klein made a similar remark at a hearing last November: “If I thought there was going to have to be another Chapter 9 (bankruptcy) case in 10 years, I probably would not confirm the plan. I’m not sure any judge would.”

In January a deputy city manager, Kurt Wilson, was promoted to city manager to replace the architect of the Stockton bankruptcy, Bob Deis, who retired. Deis said pensions are needed to be competitive in the job marketplace, particularly for police.

Vallejo officials said they considered trying to cut pension debt, but did not after CalPERS threatened a costly legal battle. The Stockton plan eliminates retiree health care, replacing a $546 million long-term debt with a $5 million lump-sum payment.

“You directed us to make sure that if we were going to endure this painful process of bankruptcy, we were going to do it in a way that meant we would never come back to bankruptcy,” Wilson told the council last week.

The Stockton exit plan, approved by most of the creditors, shows pension costs rising from about 10 percent of the general fund to near 20 percent by the end of the decade, where it remains for another decade before beginning a long drop.

That’s a big bite from the budget, diverting money from services and programs. A governor’s pension commission report in 2008 said retirement costs were about 4 percent of most local government general funds.

In San Diego and San Jose, where voters approved sweeping cost-cutting pension reforms two years ago, retirement costs were taking 20 percent or more of the general funds.

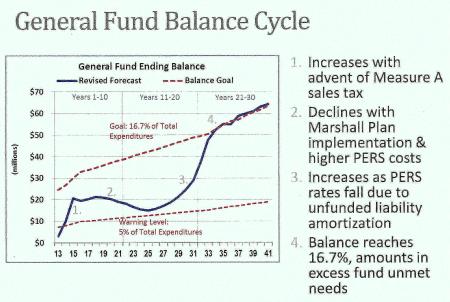

A chart in Wilson’s presentation to the council shows that pension costs are a main driver in projections that the Stockton general fund reserve will stay above a warning level of 5 percent, before climbing over three decades to the recommended goal of 17 percent.

A key part of the Stockton exit plan is Measure A, a ¾-cent sales tax increase approved by voters in November that helps pay for the anti-crime Marshall Plan and 120 additional police officers.

Vallejo drew attention with a $5.2 million budget gap. But officials said the the deficit was a “placeholder” intended to be closed by labor cuts. The gap was closed last month, mainly through retiree health care cuts imposed on police and negotiated with managers.

After deep police and firefighter cuts, Vallejo approved a 1-cent sales tax increase. Now it’s building a reserve and paying down pension and retiree health care debt. The city made an extra $6.6 million payment to the California Public Employees Retirement System.

“We are not on the brink of bankruptcy,” Deborah Lauchner, Vallejo finance officer, said last month. “We are not going there.”

Late last month Franklin filed a report from a turnaround consultant, Charles Moore, that said Vallejo’s failure to reduce pension obligations while in bankruptcy increases the likelihood of a second bankruptcy.

“This presents a troubling precedent for the City (Stockton) which, like Vallejo, proposes to squander the opportunity to restructure pension liability in its Chapter 9 case,” said Moore.

His report said Stockton pension costs, particularly for police and firefighters, are “very high, growing and unpredictable.” Safety rates are expected to reach 57 percent of pay in 2019, well above the peer average of 45 percent.

Moore said the amount of the Stockton general fund projected to be spent on pensions, reaching 18 percent in 2018 and remaining at that level for a dozen years, is “unsustainably high,” nearly double the 9.6 percent Stockton average from 1999 to 2011.

Replying to Franklin’s expert, Stockton filed a report early this month from Kim Nicholl of Segal, the actuarial firm that made projections used in the city’s plan to exit bankruptcy.

He said the Franklin report did not disclose that Segal used a more conservative annual earnings forecast than CalPERS to discount future Stockton pension debt, 7.25 percent instead of 7.5 percent.

Nicholl said Stockton cut retirement costs by reducing salaries, requiring employees to contribute 7 to 9 percent of pay toward their pensions and eliminating retiree health care.

The Franklin report does not explain why the projected Stockton retirement costs would be “unsustainably high,” said Nicholl, and does not offer any suggestions for how pension debt could be cut.

He said if Stockton ends or cuts pension contributions, CalPERS might assess a “massive termination liability” of $1.6 billion that, if not paid by the city, could severely reduce retiree pensions and leave active employees with no pension.

Among the problems for Judge Klein if he looks at whether the Stockton exit plan might lead to a second bankruptcy: Future pension costs, varying with investment earnings and other factors, are difficult to predict with much precision.

Federal bankruptcy courts can overturn labor contracts, as happened with an electrical workers union contract in the Vallejo bankruptcy. But CalPERS argues that it’s an arm of the state, and a bankruptcy court cannot interfere with state-local government relationships.

Last week, Wilson said Stockton could emerge from bankruptcy as soon as June 30 if the judge approves the exit plan. If the plan is rejected, he said, the bankruptcy could be extended another four to six months, delaying an exit until the end of the year.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Cal Pensions.