By Megan Burks.

Mayor Kevin Faulconer has said he wants to increase resources for gang policing in San Diego. Two high-profile gang cases have caught the media’s attention in recent months. And in March, state Attorney General Kamala Harris came to town to talk gangs.

For a relatively safe city, San Diego is talking about gangs quite a bit. To put it the problem into perspective, here’s a primer on San Diego’s gang landscape.

The city of San Diego has more than 4,100 gang members in 91 gangs.

The figures come from San Diego Police gang investigations Lt. Keith Lucas.

A gang is described in the California Penal Code as “any organization, association or group of three or more persons, whether formal or informal, which (1) has continuity of purpose, (2) seeks a group identity and (3) has members who individually or collectively engage in or have engaged in a pattern of criminal activity.”

An individual may be documented as a gang member in San Diego if a law enforcement officer has observed three of the following criteria: the individual has admitted to being a gang member, has been arrested for a typical gang crime, has been identified as a gang member by an informant, is seen affiliating with gang members, displays gang signs, frequents gang areas, wears gang dress or has gang tattoos.

By the way, the state of California only requires two of the above scenarios to document someone as a gang member.

Gangs are active predominantly in mid-city and southeastern San Diego.

Law enforcement agencies typically don’t release gang territory maps because a global – and worse, erroneous – look at who claims what could cause chest-puffing and violence in the streets.

When Chicago public radio station WBEZ caught flack for publishing aninteractive gang map, The Atlantic Cities tracked down a criminal justice expert who said the link between a map and gang violence is questionable. But he also brought up another point: Territories are always in flux, so any map risks mistakes.

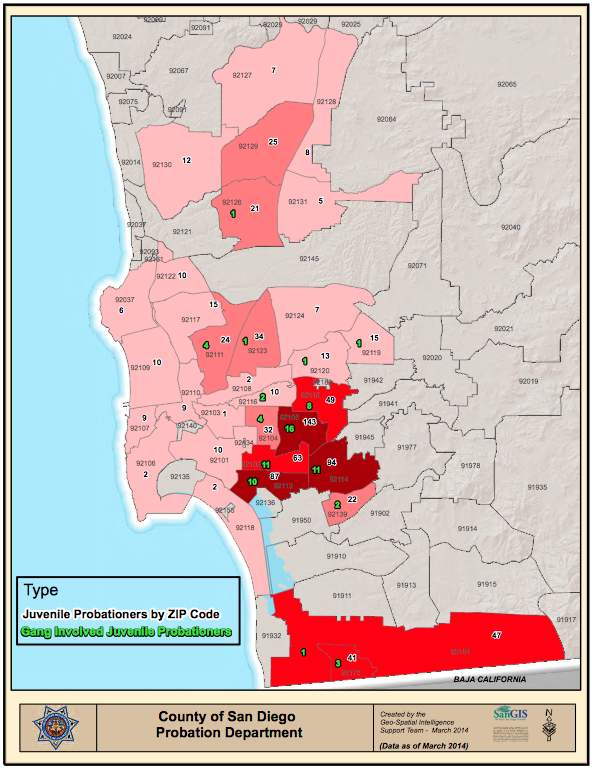

That’s why you won’t see an exhaustive map posted here. Instead, this March mapfrom the County Probation Department gives a good overview of communities impacted by gangs. A Google search will give you an idea of street-level boundaries.

Juvenile probationers and gang-affiliated juvenile probationers by ZIP code in March 2014.

The average age for joining a gang is 13.

A recent SANDAG survey on gang activity of adults and juveniles booked into county jails found the average age respondents first became associated with gangs was 13. It typically took a year for someone to become a full-fledged member. New members were often initiated through fighting, stealing or having sex with a current gang member.

Most said they joined because they sought a sense of belonging or had friends and family in gangs. Most had cousins or siblings active in the gang lifestyle, but 39 percent had at least one parent in a gang.

Gang homicides are down, but there may be more than what you see in the news.

SDPD reports how many gang-related homicides occur each year, but street outreach workers insist those numbers are significantly lower than they should be.

That’s because the police have to follow the penal code, which states a crime is only officially gang-related – and subject to stiffer sentencing – if it furthers a gang enterprise. So, an assault against a rival gang member for, say, encroaching on the gang’s drug trade is gang-related. But an assault against a fellow homeboy for snitching isn’t.

Bishop Cornelius Bowser, a former West Coast Crip who now does gang intervention work, has been keeping track of police data and “street data” on homicides since 2012. He said in his book there were five times as many gang-related murders last year than were reported. The year before that, he counted nearly twice as many.

Going on official police data, gangs claimed 7 percent of the city’s homicides in 2013; between 14 and 34 percent were gang-related during the four years prior. In Los Angeles and Chicago, where murders are routinely in the triple digits, half or more are gang-related.

Half of all gang members commit roughly a quarter of all crimes.

Countywide, law enforcement agencies reported to SANDAG that gangs are responsible for about a quarter of all crimes they see, including assaults, robberies and theft. The study suggests only half of gang members are actually committing the illegal acts.

Turf wars are the least of our problems.

Bowser said the tit-for-tat nature of gang violence started to wane with his generation. Now, it seems gangs are more focused on their financials than their territory.

“It was more like putting in work against rival gang members,” Bowser said of his past as a gang member. “It wasn’t about making the money and all of that, you know, what they do today with drugs and prostitution.”

Now violence is largely committed to protect sophisticated criminal enterprises. In fact, court documents from a recent takedown of 24 individuals for sex and drug trafficking detail two North Park gangs that are able to interact with both Bloods and Crips without repercussions and have ties to at least six street gangs.

The December 2012 indictment of those North Park gang members was an early peek into the region’s sex trade, which an Urban Institute study reveals San Diego gangs are particularly entrenched in. U.S. Attorney Laura Duffy says in the indictment that pimps recruited minor and adult women whose services they sold predominantly online. The women were taken to homes, motels and sporting events to make money; some were even transported as far as Alaska and New York, according to court documents.

One officer suggested in the Urban Institute study sex trafficking is perceived to be safer and more lucrative than other gang endeavors:

“It is not about bringing in your gang beefs and getting into a gang fight and flashing your colors. That is the unwritten rule, that you do not bring that stuff with you. When you do, obviously law enforcement will respond and then nobody is making any money. I equate it to the free trade zone or the DMZ or whatever, when you get there it is about making money. We have seen gang members who would normally be at each other’s throats or archenemies. I am not saying that they are holding hands but if they were slinging dope on a corner it is not the same dynamics that you have going on.”

But the region’s law enforcement agencies report riskier drug distribution still tops their list of concerns when it comes to gangs, according to SANDAG.

In March, state Attorney General Kamala Harris stopped in San Diego to reveal 70 percent of meth from Mexico comes through San Diego, fueling a 40 percent increase in gang membership statewide between 2009 and 2011. According to SANDAG, gang members from the Midwest are actually migrating to San Diegoand other parts of the southwest to cash in on the drug trade.

Prison and street gangs in the United States are reportedly able to buy narcotics at wholesale prices from Mexican drug-trafficking organizations. In exchange for the consistent supply, they smuggle and distribute drugs, collect drug proceeds, launder money, smuggle weapons, commit kidnappings and serve as lookouts and enforcers on behalf of the Mexican cartels, according to the FBI.

Indeed, a quarter of gang members who answered SANDAG’s survey said they’ve been asked to carry drugs across the border.

While San Diego’s gang problem pales in comparison to so-called gang capitals Los Angeles and Chicago, its ties to cross-border enterprise demands attention. It appears to have gotten Harris’. She’s proposing new statutes and task forces to address California’s complicated gang landscape, which starts in San Diego.

Harris recommends adding a narcotics special operations unit in San Diego and giving prosecutors a heavier hammer when it comes to sentencing U.S. gang members who work at high levels with Mexican drug-trade organizations.