A CalPERS report intended for policymakers, noting that a reform cuts $435 a month from the pensions of many new hires, suggests that a pay raise may be needed to “compete for quality employees.”

Gov. Brown pushed a cost-cutting pension reform through the Legislature two years ago, arguing voters needed assurance that a tax increase on the November 2012 ballot would not be eaten up by soaring retirement costs.

In the view of critics who say pensions are too generous and costly, diverting money from basic services, the reform did little to cut massive retirement debt. CalPERS estimated that in present-day dollars the reform would save $12 billion to $15 billion over 30 years.

The reform is limited to new hires because of the widely held view that a series of state court decisions, a key one in 1955, mean that pensions promised on the date of hire cannot be cut, unless offset by a new benefit of comparable value.

Last month CalPERS issued two reports, one for policymakers and one for new members, focused not on employer cost savings but on the gap between the pensions of workers hired before the reform took effect Jan. 1 last year, and those hired since then.

“To compete for quality employees, government employers may find they need to adjust salaries to make up for the reduction in retirement compensation,” said the report intended for policymakers.

The Public Employees Pension Reform Act (AB 340) cuts pensions for new hires in several ways, mainly by using a smaller percentage of final pay to multiply with years of service to set the pension amount.

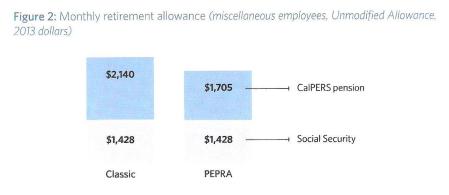

In the CalPERS policymaker report, the example is a worker with a starting salary of $46,000 who retires after 20 years at age 62. The pension for the pre-reform or “classic” worker is $2,140 a month, compared to $1,705 for the new hire — $435 less.

The policymaker report might look to some like an argument for higher salaries, particularly for new hires. The report said pensions are deferred compensation, and money contributed to CalPERS stretches dollars.

For every dollar contributed to CalPERS, said the report, government employers and employees receive an estimated $3, nearly twice the amount received from a dollar contributed to Social Security, $1.66.

CalPERS researchers using U.S. Census data found that employee compensation is a slightly smaller part of total state and local government spending in California than the national average, 30.92 percent compared to 30.98 percent.

Salaries were a lower percentage of total state and local government spending in California than the national average, 26.68 compared to 27.05, but retirement costs (pension and Social Security) were a little higher than average, 4.24 compared to 3.94 percent.

“While PEPRA is projected to decrease California state and local government retirement contributions in the long run, it also decreases employee compensation,” the report intended for policymakers concludes.

“Unless government employers adjust total compensation, this could impact their ability to attract and retain quality employees. To stay competitive and support employee retirement security, government employers may consider creative employee compensation strategies and provide employees with opportunities to enhance personal savings so they can meet their retirement goals.”

CalPERS example compares pre-reform pension with PEPRA pension

The finding that retirement costs are about 4 percent of total California government spending may surprise some local governments struggling with rising pension costs.

In San Diego and San Jose, where voters overwhelmingly approved cost-cutting pension reforms two years ago, retirement costs were 20 percent or more of the general fund that pays for most programs.

The rising cost of CalPERS pensions is a key issue in the current Stockton and San Bernardino bankruptcies and, to a lesser degree, in Vallejo which emerged from bankruptcy without cutting pension debt but still faces budget problems.

“We absolutely understand the challenges facing local governments, and frankly the state government, around a variety of different fiscal pressures,” said Ann Boynton, CalPERS deputy executive officer.

She said the report was not intended to address budget issues in specific local government budgets, but rather to show in the “macro context” how California compares with other states.

Stacie Walker, CalPERS retirement research and planning chief, said the report was not meant to take a “perspective one way or the other.” She said the report makes the point that the reform restricts “levers” negotiators can pull at the bargaining table.

In addition, said Walker, the other report intended for new members, who may tend to be on “autopilot” with the security of a pension, shows how much they need to save or how much longer they must work to regain losses under the pension reform.

“The hypothetical CalPERS PEPRA employee scenarios in this study demonstrate the need for these employees to save between $373 and $1,480 per month throughout their careers or work 2.5 to 5 years longer to retire with the same income as Classic employees,” said the report for new members.

The report intended for policymakers briefly mentions the possibility of new hires working longer to close the pension gap with pre-reform or “classic” members. But the example of a $435 monthly cut does not show the added years that would close the gap.

In the examples in both reports, the hypothetical member retires with 20 years of service, close to the average for CalPERS members. But if the hypothetical member worked 30 years, there would be no pension gap between classic members and new hires.

The widely used formula for classic members in the example, “2 at 55,” and the equivalent PEPRA formula, “2 at 62,” both replace 75 percent of the final salary after 30 years of service, not counting Social Security, according to CalPERS benefit tables.

A 30-year career is used in a national report issued last month by the Center for State and Local Government Excellence and the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, which also focuses on the impact of reform on worker pensions.

The national report looked at 24 of about 45 states that have enacted cost-cutting pension reforms in recent years. The California reform is estimated to have reduced the average benefit by 2.4 percent, well below the 7.5 percent average for states in the study.

Because PEPRA yields the same pension as the classic formula after 30 years of service, most of the 2.4 percent cut apparently results from a longer final pay period used to calculate the pension, a three-year average rather than one year.

Brown was not able to get legislative approval of one of the main parts of his pension reform, a federal-style “hybrid” plan for new hires combining a lower pension and a 401(k)-like individual investment plan.

“Hybrid plans adopted in five states produce a wide range of retirement incomes,” said the national report.

“The Rhode Island, Tennessee and Utah plans may increase retirement income, a fact that can be partially attributed to higher required contributions to their defined contribution plans. Georgia and Virginia have lower statutory contribution rates, and their hybrid plans may produce lower retirement incomes.”

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at CalPensions.