Originally posted at Next City.

By Nancy Scola.

Just this week and in the company of “hashtag” and “tweep,” the compound phrase“crowdfunding” was added to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, glossed as “the practice of soliciting financial contributions from a large number of people especially from the online community.” Fueled by the streamlining of online payments in the last several years, social networking, and the rise of trusted platforms like Kickstarter and IndieGoGo, crowdfunding has taken hold, funneling billions of dollars to all sorts of products, start-ups and dreams.

Rodrigo Davies, a former journalist who’s now a civic technologist with MIT’s Center for Civic Media, says there’s one vibrant subgenre of crowdfunding that’s being unduly overlooked, not just by the public but fellow researchers, too. What he and others call “civic crowdfunding” is the subject of his recently completed master’s thesis for MIT’s Department of Media Studies. “Civic,” admits Davies in Civic Crowdfunding: Participatory Communities, Entrepreneurs and the Political Economy of Place, is a “slippery and contested term,” but he uses it here to talk about raising funds for projects that produce a shared public good, like a community chicken farm in Brooklyn that raised more than $6,200 on the platform ioby.org and then “distributed free eggs to local residents and visitors to promote healthy eating.”

And after two years of studying the raising of sums online for the common good, what has Davies learned? “Civic crowdfunding projects tend to succeed more often,” he says by phone, but those efforts tend to be smaller in scope and more locally funded than crowdfunded projects writ large. They, too, tend to involve utterly non-controversial challenges, like backing free eggs. That raises questions he says about both why more people aren’t indulging in civic crowdfunding and whether it can scale.

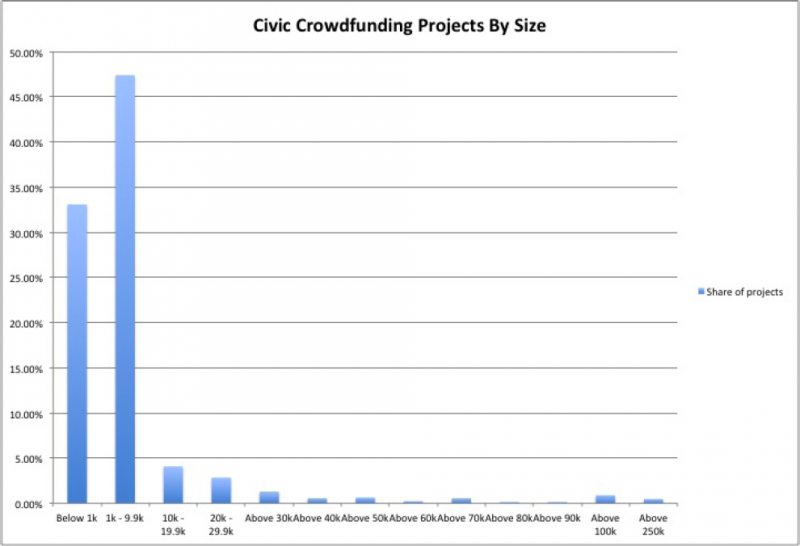

If there’s a “typical” project in the civic crowdfunding market, writes Davies, it’s indeed “a smallscale garden or park project in a large city that produces a public good for an underserved community” and raises about $2,000. Indeed, the vast majority of civic crowdfunded projects raise less than $10,000, or 1/300th of what “Scrubs” star Zach Braff raised on Kickstarter to fund his new movie:

One other finding of Davies: There aren’t tremendously many civic crowdfunding projects in existence. Looking at the platforms mentioned above as well as civic-centric ones like Citizinvestor, Neighbor.ly and the U.K.-based Spacehive, Davies identified a few more than 700 successfully funded civic campaigns launched since 2010. With a median pledge of $62, they raised some $11 million. Impressive, perhaps, but just a tiny sliver of a crowdfunding market that, by one estimate cited by Davies, comes in at about $1.2 billion a year.

Still, it’s a subgenre with a certain record of success, measured either by reaching the “trigger” point for collecting donations set by some sites or, on others, a bar of half the donations asked for by the project organizers. Indeed, points out Davies in his paper, “If Kickstarter were to have a ‘Civic’ category for projects on the site alongside the likes of music, video games and movies, it would be the platform’s most successful category in terms of proportion of projects funded.”

And after spending the last couple years surveying the field and digging into the data, Davies has an idea of why that might be. “It speaks to a demand for small-scale local interventions that have an immediate impact on people’s quality of life,” he says. “They’re appealing to people whose civic impulse, if you like, hasn’t been triggered too much in the past.” One part of the attraction, he says, is that this is a medium where chipping in even a few dollars registers, often by getting your name included in a public, linked list of project backers.

Such micro-philanthropy with some of the public recognition traditionally reserved for the big-dollar donor is a new thing, says Davies. “Sometimes you’re giving money to an organization and it feels like if you’re not giving a large amount — enough to get your name on a park bench, say — your donation doesn’t matter too much.” That sets up a dynamic that he calls “bench or nothing.”

Enter civic crowdfunding. “This,” Davies says he’s learned, “is energizing people to say, ‘Well, hang on. Your small donation can count for something and there are ways that we can acknowledge it.” That can be attractive, says Davies, especially to those new to the philanthropic space. Kicking over a few dollars to support a community center in South Wales, bike-share in Kansas City, or a public art project in São Paulo — projects detailed in his paper — can be a painless way to indulge that civic impulse.

“You’re seeing a new slice of people appealed to with these projects,” says Davies, “who say, ‘There is something I can do to have an impact in my community, even if I can only donate 20 or 50 dollars.’” (Data point: The going rate for getting your name on a new bench in L.A., to pick one city, is $3,500.)

Of course, free dairy products are one thing, and the projects in South Wales, K.C., and São Paulo demonstrate that far-reaching endeavors can be pulled off on occasion. But Davies says that there’s a growing hunger to see high-dollar projects pulled off with the same regularity that the farmers in Brooklyn are delivering eggs. “Some people have much bigger ambitions for it, whether that’s people in government or civic non-profits,” says Davies. “They’d love to see crowdfunding realize big projects, which has been done in a small number of cases so far. So we know that it’s possible, but it not really being done.”

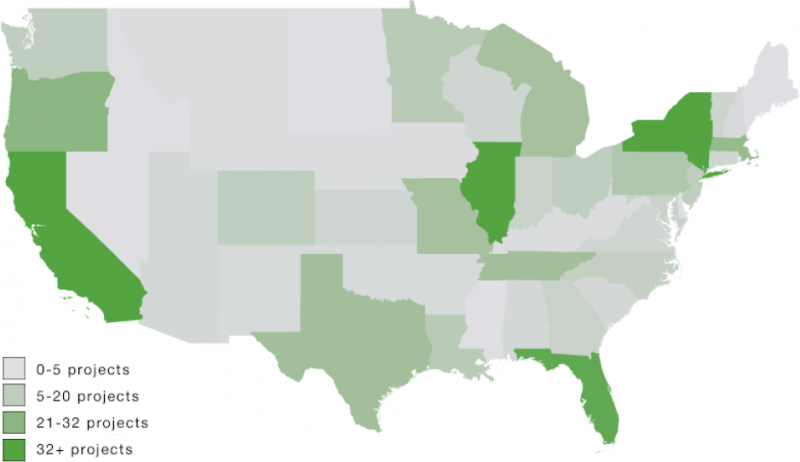

What might be holding civic crowdfunding back? Davies has a few data-driven theories. Check out the map above and note that the civic crowdfunding projects he counted in his round-up are concentrated in just a few states, New York in particular. In fact, the Empire State accounts for just less than half of all the civic crowdfunding projects of which he took stock. That’s not surprising, says Davies in his paper, “since both IOBY and Kickstarter are based in [New York City], and IOBY tends to recruit projects for its platform.” And then he adds, “This might also explain the performance of Florida, since IOBY has a secondary headquarters in Miami.” That, he says, suggests that civic crowdfunding projects are still at the stage where they’re most appealing to those who will benefit the most from them. That, too, is unsurprising, but it hints, perhaps, at a natural cap on the appeal of some place-tied civic projects.

And then there’s the fact that, even if today’s crowdfunder isn’t after a park bench, she is, in aggregate, more eager to put her money to a park than to anything else. Indeed, nearly 30 percent of civic crowdfunding projects, reports Davies in his paper, are for a garden or a park. (Funding events comes in at 14 percent, and next up is educational programs, at 11 percent.) That, too, he says, by phone, might hint at a limit on what civic crowdfunding can accomplish. “If the crowd is only willing to fund things that are uncontroversial,” he says by phone, “that tells us that crowdfunding isn’t good for providing everything. If there’s a drug rehabilitation center needed in a neighborhood, maybe crowdfunding isn’t going to provide that.”

There’s a decent chance, though, that someone will test that theory soon, which will give Davies more to study. He’s off to Stanford now to work on his PhD.

His full paper is here.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Next City.