A decade ago new accounting rules directed state and local governments to begin calculating and reporting debt owed for health care promised retirees, which for state workers turned out to be more than the debt owed for pensions.

In a new step to expose hidden debt, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board last week proposed that retiree health care debt or “unfunded liability” be reported on the face of government financial statements, not buried inside.

The board chairman, David Vaudt, said in a news release retiree health care is “a very significant liability for many state and local governments, one that is magnified because relatively few governments have set aside any assets to pay for those benefits.”

Most government retiree health care is pay-as-you go, covering part or all of annual insurance premiums. No money is set aside, as in a pension, to invest and yield earnings, lowering long-term costs and cutting debt passed to future generations.

State Controller John Chiang, who in 2007 issued the first estimate of state worker retiree health care debt, said in a new report last March the unfunded liability for pay-as-you-go state worker retiree health care is $64.6 billion.

In contrast, the unfunded liability for state worker pensions is $49.9 billion as of last June 30, a CalPERS valuation said in April. State worker pensions have a low funding level, 66.1 percent of the projected assets needed for full funding.

State worker retiree health care is unusually generous. A 12-point pension reform plan issued by Gov. Brown in 2011 mentioned “the anomaly of retirees paying less for health care premiums than current employees.”

The state pays 100 percent of the premium of the retiree (the average of several large plans) and 90 percent of dependent premiums. For active workers, the state usually pays 80 or 85 percent of the worker premium and 80 percent of dependent premiums.

The governor mentioned retiree health care at a news conference last month while proposing a revised state budget plan that includes a long-term funding solution for the troubled California State Teachers Retirement System.

“Now this doesn’t handle it all,” Brown said. “We still have retiree health. We have the judge’s retirement system. We have got lots of other stuff here, and we will handle it. But this (CalSTRS plan) is taking a big bite out of our long-term obligation.”

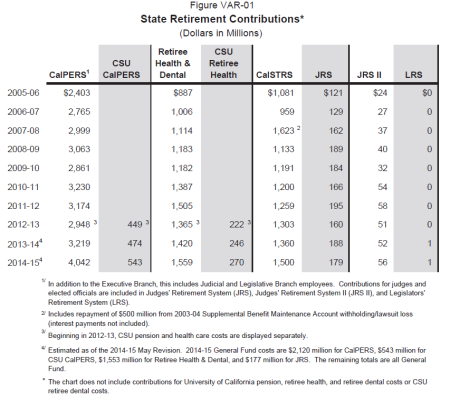

The chart shows retiree health care has been the fastest-growing state retiree cost, doubling in a decade. Nearly all of the $1.8 billion retiree health payment next fiscal year comes from a $108 billion general fund that pays for schools and other programs.

An example of the disregard for long-term retirement debt that the accounting board is trying to change: Legislation in the early 1990s created an investment fund for California state worker retiree health care, but lawmakers never put money in the fund.

The rule change in 2004 telling governments to phase in the calculation and reporting of retiree health care debt was followed by the controller’s initial report on state worker debt three years later.

After a year of hearings and study, the top recommendation of the governor’s Public Employee Post-Employment Benefits Commission in 2008 was “prefunding” retiree health care, setting aside money to invest and help pay for future obligations.

“The best way to ensure that government promises are kept is to provide prefunding for these benefits,” the chairman, Gerald Parsky, said in the opening message of the commission report.

For local governments choosing to prefund retiree health care, the California Public Employees Retirement System in 2007 established an investment fund, which had 375 employers last August with total investments worth $3.6 billion last week.

The CalPERS retiree health care fund (the California Employers Retiree Benefit Trust) lets employers choose among three conservative investment strategies with varying risk and returns.

The median 20-year return expected for the three strategies ranges from 4.61 percent a year to 3.39 percent. That’s roughly similar to recent yields on 20-year municipal bonds used in the new GASB proposal to report retiree health care debt.

An employer’s report could use the expected return on a retiree health care investment fund to pay long-term debt. But if that falls short, or there is no investment fund, the remaining debt would be reported as if paid with a 20-year municipal bond.

A “crossover” from the expected investment return to a high-quality municipal bond, the presumed cost of borrowing, may not be much of a change for employers in the CalPERS retiree health care fund because of little difference in the yields.

But a similar GASB reporting rule is taking effect for pension funds that critics say have an overly optimistic expected return on their investments, 7.5 percent a year for CalPERS and the California State Teachers Retirement System.

Closer alignment with the new accounting rule was one of the goals mentioned when CalPERS adopted a new actuarial method for pensions last year, aimed at reaching full funding in 30 years rather than decades later under the old method.

Now CalPERS expects little if any “crossover” to a lower-yielding bond rate under the new pension rule, and therefore little change in its reported unfunded liability. But without a costly funding solution, the CalSTRS investment fund is expected to be depleted in about 30 years.

The CalSTRS board was told last September that under the new rules a $71 billion unfunded liability could soar to a $166.9 billion “net pension liability,” an estimate since outdated by another year of investment returns and other factors.

Whether big new pension debt would be reported by school districts next year, possibly lowering credit ratings and increasing borrowing costs, is not clear. Legislation enacting a CalSTRS funding solution this year would avoid much of the problem.

Part of the reason that retiree health care has not been prefunded like pensions may be uncertainty about whether the health benefit, unlike pensions, can be cut or even eliminated.

Under a series of court decisions dating back to at least 1955, pensions offered on the date of hire are widely regarded as a “vested” right, protected by contract law, that can only be cut if offset by a comparable new benefit.

A benchmark ruling on retiree health care by the state Supreme Court in 2011 said a contract with vested rights “can be implied under certain circumstances from a county ordinance or resolution” if an intent to do so can be shown by evidence.

Since then there have been several retiree health court rulings, one in Los Angeles finding a contract and others in San Diego and Orange and Sacramento counties allowing cuts. Last month the state Supreme Court declined to hear a San Diego decision appeal.

A GASB fact sheet last week, using the governmental term for retiree health care (Other Post-Employment Benefits), broadly defined liability as a social, legal or moral requirement.

“The possibility that a government could change or end the OPEB it has promised in the future does not change the fact that, as of the date of the financial statements, it had a present obligation to fulfill its promise to provide OPEB,” said the fact sheet.

GASB plans to post an “exposure draft” of the new retiree health rules on its website by the middle of this month, seeking comment from stakeholders by Aug. 29. Public hearings are scheduled Sept. 10, 11 and 12 at locations not yet announced.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at CalPensions.