Originally posted at Next City.

By Denise Linn.

With Google Fiber’s gigabit fiber networks in Kansas City, Austin and Provo, and the company expressing interest in negotiating with nine other metro areas, competitors and imitators have responded. The first half of this year saw a steady stream of upgrade announcements from AT&T, Cox, C Spire and CenturyLink. However, these operators have not cast a wide enough net to meet the overwhelming demand for faster speeds. (More than 1,100 municipalities answered Google Fiber’s initial call for applicants in 2010.) What if your city isn’t being courted? Fortunately, the unselected are not doomed to wait for a Google Fiber, AT&T, or other national service provider to ride into city hall on a white horse. There are other options.

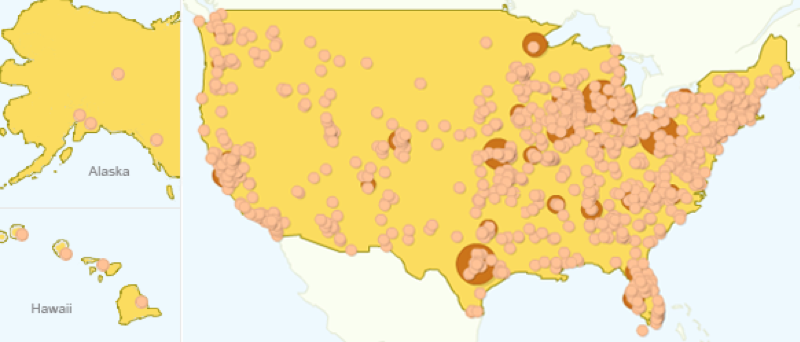

Each small dot represents a government response to Google Fiber’s RFI, and each large dot represents locations where more than 1,000 residents submitted a nomination. (Source: Google Fiber, 3/26/2010)

While negotiating with a private upgrader is relatively low risk from a city government perspective, it is not a guarantee nor is it the only pathway to gigabit connectivity. There are innovative, alternative models for building and operating gigabit networks. The cities below thought outside the Google Fiber box, adopting or encouraging feasible projects that suited local needs, and set an example for others to follow.

Consider a Public-Private Partnership Playing to Local Strengths: Urbana-Champaign, Illinois

At the end of May, UC2B — a non-profit consortium led by the university communities of Urbana and Champaign and the University of Illinois — announced a new model for gigabit connectivity. They would pursue a public-private partnership with iTV-3, an Illinois-based ISP.

Years ago, UC2B leveraged federal grant money and local matching funds to construct a high-speed fiber network and built out first in low-income and low-adoption areas. The new public-private partnership means that iTV-3 will now operate that existing UC2B network and extend its reach to serve even more residents, institutions and businesses. Though the city will not have control over the network or collect the revenue, it does not have to absorb the risk of costly infrastructure investment.

Consider a Non-Profit Model: Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland benefits from the existence of OneCommunity, a non-profit fiber network spanning 2,460 miles that was started by former Case Western Reserve University CIO Lev Gonick. OneCommunity services the key anchor institutions in Northeastern Ohio (government offices, schools, universities, hospitals, etc.) and collaborates with the local community on broadband adoption projects and digital literacy training. Currently, city officials in Shaker Heights, Ohio are considering a partnership with OneCommunity to extend fiber into its commercial districts in order to attract more economic development. OneCommunity has also formed a for-profit subsidiary, Everstream, which will provide high-speed Internet to businesses — the revenue of which will circle back and feed the organization’s non-profit programming.

Consider Adopting Practices That Assist Local ISPs: East Lansing, Michigan

Uniting a diverse group of stakeholders under its “Gigabit Ready” effort, Lansing created an attractive environment for its existing ISPs to upgrade. The Lansing Economic Area Partnership (LEAP), along with Michigan State University, non-profits, and commercial property managers aimed to lower barriers to high-speed broadband deployment. To align incentives and capitalize on their partnership with local development companies, the Gigabit Ready Coalition created a Gigabit Certified Building Program operating similarly to the well-known LEED program. Now, local ISP Spartan-Net and property manager DTN Management Co. have partnered to bring residences and apartment complexes in East Lansing gigabit speeds.

Consider Investing in Telecommunications as a Public Utility: Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is an interesting case, not because they built a fiber-to-the-premises network themselves as part of a holistic smart grid strategy, but because they were the first city in the U.S. to get to a gigabit. Chattanooga has had their network, EPB, long enough that other cities can look to them for evidence of the qualitative and quantitative benefits of gigabit speeds. Since service began, both Volkswagen and Amazon moved into Chattanooga. Also, initiatives like GigTank have developed to foster the city’s budding start-up community. In his 2012 New York Times op-ed “Obama’s Moment,” Tom Friedman pointed to Chattanooga EPB’s innovative ripple effect: “That network was fully completed thanks to $111 million in stimulus money. Imagine that we get a grand bargain in Washington that also includes a stimulus of just $20 billion to bring the 200 biggest urban areas in America up to Chattanooga’s standard. You’d see a ‘melt-up’ in the U.S. economy.”

Many other cities have also invested in a telecommunications utility model. Other successful examples can be seen in Leverett, Mass., Wilson, N.C., and Bristol, Va., just to name a few.

Consider Incrementally Investing in Telecommunications as a Public Utility: Gainesville, Florida and Westminster, Maryland

Even if a city explores a public option for gigabit service, it doesn’t have to go all in right away.Gainesville Regional Utilities (GRU) has connected businesses, community anchor institutions and large apartment complexes around the University of Florida to 1 gigabit, 100 Mbps, and 10 Mbps speeds, but not most residences yet.

In 2012, Westminster, Md., began a pilot fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) project connecting selected areas of the city to high-speed Internet. Building on that work, they plan to expand and install citywide dark fiber by 2017 — the idea being that, once the public infrastructure is built, a third-party provider can actually operate the network going forward.

Consider the Pilot Innovation Zone Approach: Blacksburg, Virginia

Blacksburg, home of the Virginia Tech Hokies, is also home to a free gigabit WiFi network that covers about 40 percent of the downtown area. Initial funding to install the fiber at two locations was modest — just about $90,000 — and was collected through acrowdsourcing campaign started by TechPad, a local co-working and hacking community. While the future of the network is unclear, the first few years of the project were meant to gauge local demand for faster speeds and nail down a sustainable funding model.

Consider a Regional Strategy to Attract Private Investment: North Carolina

North Carolina Next Generation Network is a collection of four universities (Wake Forest, UNCChapel Hill, Duke and NC State) and six municipalities (Carrboro, Cary, Winston-Salem, Chapel Hill, Durham and Raleigh) that shared knowledge and resources to release a single RFP. It articulated the region’s objectives and sought vendors to build and operate a gigabit fiber network. The RFP was released in February of 2013 and attracted eight responses. Since then, several of the NCNGN cities have caught the attention of major national providers. Just recently Winston-Salem, Raleigh andDurham finalized agreements with AT&T.

Of course, each of the successful cases above were realized with necessary funds, time, community support and leadership. Also, at the time these projects unfolded, none was prevented by state legislation limiting community broadband networks. At present, 20 states have passed such laws. Recently, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler came out as a vocal opponent of these legal barriers. The newCoalition for Local Internet Choice similarly defends the broad principle of local decision-making — specifically defending a city government’s right to go forward with municipal broadband projects.

City governments are well positioned to engage with the community and carve out a tailored, local broadband strategy. Everyday it seems that new cities like Huntsville, Ala. and Boulder, Colo. step up, articulate their demand for gigabit speeds, and take ownership over their community’s connectivity. While the Google Fiber narrative is exciting, it’s not the only gigabit story out there with a happy ending. There are other models to follow and likely more to discover in the years to come.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Next City.

Denise Linn is an Ash Center summer fellow in innovation with the Gig.U project and is a master in public policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.