By Ted Grantham and Joshua Viers

California water experts have long known the amount of surface water granted by water rights far exceeds the state’s average supplies. Historically, the over-allocation has not raised much concern; in most years, there has been enough runoff of rain and snowmelt to go around.

But circumstances are changing. California is suffering the third driest year in a century and demands for water are at an all-time high. The huge gap between allocations and natural flows — coupled with great uncertainty over water-rights holders’ actual usage — is increasingly creating conflicts between water users and confusion for water managers trying to figure out whose supplies should be curtailed during a drought.

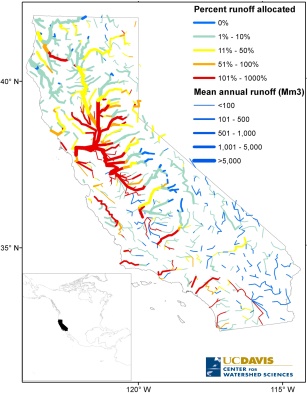

To understand where and to what degree California rivers have been claimed, we mappedall appropriative water rights recorded by the State Water Resources Control Board. We quantified the total “face value”, or maximum annual diversion volume, of water rights for all rivers and streams and compared this data with estimates of water supply.

We found that water rights exceed average supplies in more than half of the state’s large river basins, including the Salinas River, where water-rights claims amount to three times the average flow, and the San Joaquin River, where water rights exceed flows by as much as eightfold.

Not only are many rivers over-allocated but the amount of water actually used by water-rights holders is poorly understood. Comparisons of allocations with water use suggest that in most of California, only a fraction of claimed water is being used. Statewide, appropriative water-rights claims for consumptive uses are about five times greater than average surface-water withdrawals.

The Associated Press recently reportedthat the state water board is unable to track the water usage tied to many of California’s oldest and largest water rights (Dearen & Burke 2014). The state system primarily relies on self-reported water use records, which are riddled with errors, even for the some of the state’s largest water users.

In a well-functioning water-rights system where allocations are closely tracked and verified, over-allocation is not necessarily a problem. During water shortages, the state would order holders of junior appropriation rights to curtail use. When water is abundant, most water-rights holders should be able to fully exercise their claims.

Inaccurate accounting, however, threatens the security of water rights — particularly when water is scarce. Earlier in this drought year, for example, the water board sought to protect fish in some watersheds by threatening curtailments of water rights held by allusers within those drainages. More targeted cutbacks might have been sufficient if the agency had accurate water-use information.

The lax water accounting has intensified conflicts between users during the drought. Operators of the state and federal water projects recently asked the water board to investigate diversion practices by farmers in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. As the Sacramento Beerecently reported, the water agencies suspect farmers are taking water released from upstream dams that is intended for consumers elsewhere. The California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, a group often allied with Delta landowners, has countered with a formal complaint to the board alleging that the agencies are illegally diverting water from rivers that flow into the Delta. (Weiser 2014).

Innovative approaches to California’s water management challenges also are dependent on accurate water-rights accounting (Hanak et al. 2011). For example, water markets rely on transparent and accurate quantification of water transfers. Uncertainty in water rights may also discourage conjunctive management of surface and groundwater to improve water supply reliability (Draper et al. 2003).

In over-prescribed systems, water needed to meet new and evolving demands will likely require curtailment of water rights. This is not as daunting or threatening as it may seem.

Impacts to private water rights will likely be minimal because public agencies control the bulk of the state’s water supply. Tightening the water accounting would have a much greater effect on state and federal water project operators, water utilities and irrigation districts that collectively hold rights to 80 percent of the allotted water — compared with less than 1 percent held by individuals.

Major policy changes may not be necessary to improve California’s water rights system. California law already allows re-allocation of water rights to address evolving societal needs and changing environmental conditions (Littleworth and Garner 2007). For example, the public trust doctrine establishes that the government has an ongoing duty to safeguard natural resources (Frank 2012). California’s Fish and Game Code 5937 is an expression of that doctrine, requiring dam owners to provide enough flows below impoundments to maintain fish in good condition.

The state water board, however, will need legislative authority and funding to improve the recordkeeping and effectively enforce water rights. According to board staff, the agency does not have the resources to systematically verify water usage or check even the most obvious mistakes in the records. Yet the board still relies on these inaccurate data in deciding how and where to grant water-rights permits (Dearan and Burke 2014).

Improving the water-rights system, of course, will not alone solve California’s myriad water management challenges (Hanak et al. 2011). But without better quantification and regulation of water rights, prospects of reconciling competing water demands in a drought-stricken state will remain bleak.

The tools and technology to quantify water supplies and accurately track usage are at our disposal. All that is lacking is political will.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at CA Water Blog.

Ted Grantham, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey, analyzed the state water-rights database as a postdoctoral researcher at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. Joshua Viers is director of the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS) at UC Merced. Their study of the California water rights system was published Aug. 19, 2014