By Andrew Keatts.

One way to avoid big fights between developers and communities is for the city to play mediator before a project is even proposed.

Updating community plans is meant to do exactly this. A fresh blueprint calls out stuff neighborhoods need and paves the way for a reasonable amount of new development to help satisfy a growing region.

Done right, it saves everyone involved — developers, residents and the city — lots of time and money, because some of the biggest and ugliest development fights never happen.

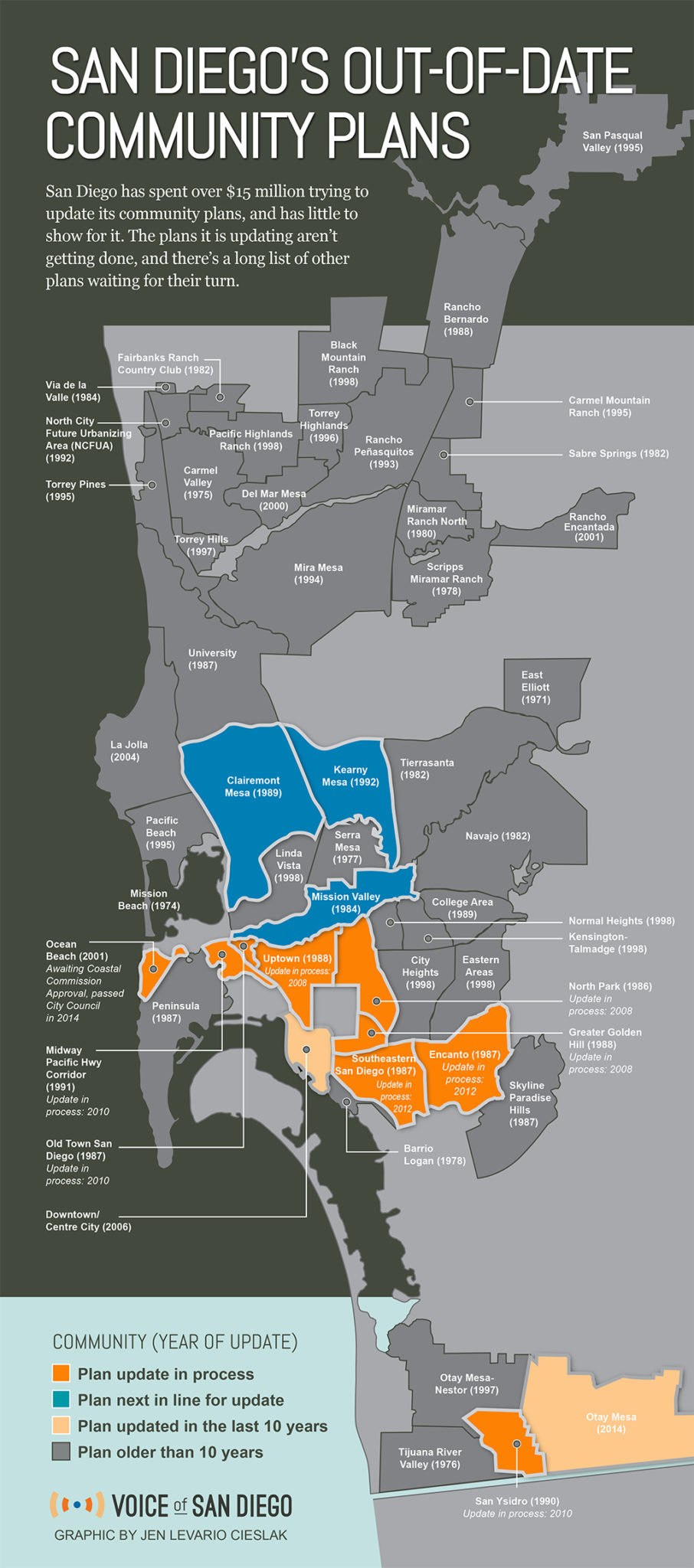

The city knows this. That’s why it’s spent more than $15 million over the last 13 years trying to update community plans in 12 neighborhoods, including Barrio Logan, North Park, Encanto, San Ysidro and Ocean Beach.

But the city has just one fully adopted plan to show for it.

This fix for delay and dysfunction within communities has itself been marked by delay and dysfunction. It’s been plagued by poor consultant management, trying to do more work than is really necessary, bad decisions and inconsistent funding.

Now, the city’s starting new updates in Mission Valley, Clairemont Mesa and Kearny Mesa. Planners say they’ve learned their lesson and this batch will be different.

How We Fell Behind

In 2008, San Diego finished putting together its citywide outline for new development, called the general plan.

It solidified “city of villages” as the mantra for growth. For the good of the environment and its own economy, the plan said, the city needed new housing located along transit corridors and near job centers.

That marked a big change in where development was supposed to go. Instead of new homes cropping up in the city’s northern and eastern edges, they were now targeted for long-established neighborhoods near the city’s core.

But when the general plan was finished, those urban neighborhoods weren’t ready to accept the new growth they were supposed to have. The development guidelines in those neighborhoods had been collecting dust.

Since 2008, efforts to rewrite those plans haven’t amounted to much.

In December 2012, well into the process, the planning department tried to explain why things were taking so long. It set new deadlines for each community. It’s since blown past all those deadlines, too.

Some of the delays came, ironically, from the planning department’s bad planning.

The department acknowledges it didn’t handle technical things like traffic and environmental studies appropriately. It wasted lots of time trying to be too detailed with both of them.

And it wasted more time locking up consultants to complete those studies. Every time the department needed to hire an outside firm, it issued a call to everyone who might be interested, ran a full selection process and negotiated a new contract. Every one took about a year to process, city officials said.

Delays often came down to money. When the economy tanked, so did the city’s budget, and funding for plan updates went away.

“You had the city go through a really difficult financial time where there weren’t resources to hire the people and complete those community plan updates,” said David Graham, the city’s COO in charge of planning. “To some extent, they were effectively suspended for a period of time.”

Of the $15.36 million the city’s spent trying to update community plans, 44 percent—or $6.8 million—has gone to contractors. The rest has paid for staff time and administrative costs directly related to working on the updates.

But nothing exemplifies the city’s missteps more than what happened when it tried to simultaneously update plans in North Park, Uptown and Golden Hill.

Planning staff refers to that bunch of updates as “the cluster” because the neighborhoods are contiguous, not because it’s been a disaster. Both definitions of “cluster” fit the description of what’s happened.

Come July, the city will have spent five years updating the cluster.

To date, planners till haven’t released final drafts for the plans — preliminary decisions on zoning maps, economic studies and policy determinations that go into environmental review and are the basis for future debate.

“It’s obvious we need to acknowledge it has taken way, way too long,” said Nancy Bragado, the city’s deputy director for long-range planning.

The communities themselves are past antsy.

“I can say, for us, this is getting stale,” said Leo Wilson, chair of Uptown’s community planning group. “You’re hearing the same comments and conversations we’ve already had. It’s time to get a draft out.”

Bragado agrees. That’s one thing the city’s learned: It’s possible to have too much community input.

Vicki Granowitz, chair of the North Park planning group, had always hoped the group could get each section of the plan as it was finished, so it could provide detailed feedback on each one. Now, it looks like it’s getting a full dump all at once, just what Granowitz feared.

“Now it’s going to be rush, rush, rush to get it done,” she said. “Honestly, I’m ready for it to be over, but I’m concerned that we get it right.”

The North Park, Uptown, Golden Hill experience has convinced the city it shouldn’t try to handle adjacent neighborhoods as a group.

“We shouldn’t call them clusters,” Bragado said. “You have different communities, different planning groups and different consultants. You should treat them individually. That’s a lesson learned.”

The city says drafts are coming by the end of the month, and it hopes to start having final public hearings on the plan next summer. That’d give it a chance of finishing before the end of 2016, eight years after it started the process.

The city’s pulled together some other improvements it hopes will lead to better results for its next batch of updates in Mission Valley, Clairemont Mesa and Kearny Mesa.

It says three years is its new benchmark to get a new plan written.

Getting Better

Some of the reasons plans haven’t been fully completed weren’t because of anything city planners did.

The City Council approved a new plan for Barrio Logan in September 2013. Then the shipbuilding industry funded a campaign to veto it, and voters overturned the plan last June.

And the Ocean Beach plan is effectively finished. The Council approved it last summer, 13 years after the update started. It’ll become official once the Coastal Commission signs off.

Beyond figuring out that community input eventually reaches diminishing returns, the city’s learned other lessons it hopes will make things go smoother.

• Managing Consultants

City staff relies on consultants for a lot of the technical work that requires specific expertise for each plan. In the cluster, for instance, the city spent $664,347 with outside firms.

“We had a previous philosophy to use a lot of consultants for creative balance, to create a diversity of ideas,” Bragado said. “It was an administrative nightmare.”

Rather than planning, planners spent their time juggling contracts and shuffling paperwork for every project.

And they needed to go through the yearlong process each time they needed some consultant work. The city’s adopted a new system it hopes will address the problem. It’s inking five-year contracts with a small list of consultants in three different areas: environmental work, traffic engineering and general land-use planning.

Since all the consultants are under contract, the city can just issue them work assignments for whatever they need. The only requirement is that they all end up with the same amount of work at the end of five years.

Bragado said it could shorten the wait-time to approve contract work from a year to a month.

• Do Less

Granowitz, the North Park chair, said the city spent too much time planning for areas that weren’t going to change, anyway.

“They were overambitious,” she said. “Instead of saying we are going to rewrite the whole plan, let’s admit what doesn’t need to be rewritten. They could have saved an enormous amount of time.”

It gets back to the city’s acknowledgment that it was going into too much detail on traffic and environmental reports.

Bragado said city planners were accustomed to doing traffic and environmental studies for specific projects, not entire communities.

For a specific project, they’d try to figure out every car-related impact it would have on the surrounding area. They tried to bring that same precision to every intersection in every community.

Now planners are shifting their focus to key, representative intersections and places they know are going to be home to lots of new development.

“It’s about getting the right balance of analysis,” Bragado said.

It’s the same story on environmental analysis.

One big benefit of new community plans is having environmental oversight for new development done upfront. That saves developers the time and money of doing it themselves, and residents know ahead of time what’s permitted and what benefits they’ll get in exchange.

But too often, Bragado said, the city tried to cover every possible project that might ever be proposed.

“Our standard now is (do enough environmental review) to cover reasonably expected development, with a bit more done in village areas to act as incentive to develop there,” she said.

Developers that want to build more than that will have to handle it on their own, but they’ll build off of the city’s review for a less intensive development.

The city’s also trying to build a data-driven rubric to decide which communities need new updates the most.

“If there are a lot of amendment requests, something’s wrong,” Bragado said.

But first, it hopes to hold its three new communities to the new three-year update standard. That’ll mean the mayor and Council funding the new updates, as they did for Mission Valley in last year’s budget, and not shifting priorities as they had when the city’s budget got tight in the past.

[divider] [/divider]