By Steven G. Martin.

The Proposition 1 Water Bond, initially enacted by the state Legislature last August, allocates $625 million toward recycled water projects through the State Water Resources Control Board. The funding is authorized, but how do you get it?

The SWRCB reports that its guidelines for obtaining Prop.1 Water Bond Water Recycling Funds are nearly ready for rollout, and that “now” is the time to submit your initial applications for recycled water project funding. (“Applications and Process” are here.)

On April 17, in the midst of the current unprecedented drought, the SWRCB’s staff members presented a workshop clarifying the process for obtaining recycled water funding to a filled board room at Eastern Municipal Water District in Perris, Calif. The following is a recap of that presentation.

PROJECTS: Water recycling funds can be used for projects treating municipal wastewater to offset their cost and augment supplies. Stormwater projects are not currently covered, as the SWRCB is considering whether those fit the “recycled” definition originally intended to offset the initial source for the recycled water. Also, private recycled system conversions for acquiring customers are likely to be excluded, since only public projects are allowed. The SWRCB is requiring that at least 50 percent of the intended project capacity be delivered upon completion and initial implementation. For some projects, the ability to produce this capacity upon completion may seem unreasonable. So, considering and addressing this requirement may be important when drafting an application for the proposed project.

GRANT FUNDING: Prop. 1 provides $625 million toward SWRCB-funded recycled water projects, which is anticipated to be distributed over the next four years, with approximately $130 million slated for appropriation in this year’s budget. The funds will be split 50-50 between loans and grants, with the loan repayments recycled back into the program to fund later applications at the same 50-50 loan-grant distribution ratio for multiple cycles, until the funds are ultimately depleted.

Under the current draft guidelines, “planning grants” will be issued providing up to a 75 percent state-funded share, and up to a $75,000 grant. Also, “construction financing” is allowed at half the State’s general obligation bond rate for a 30-year term and with allowances for design and construction that follow the current State Revolving Fund Policy. The program will also provide “construction grants” up to a 35 percent state share, and up to a $15 million grant, with up to 15 percent of the grant eligible for construction management, contingency, and other construction allowances. Construction projects located entirely within a small and disadvantaged community, which the SWRCB has yet to define, can receive an even greater state shares (40 percent) and maximum grant amounts ($20 million).

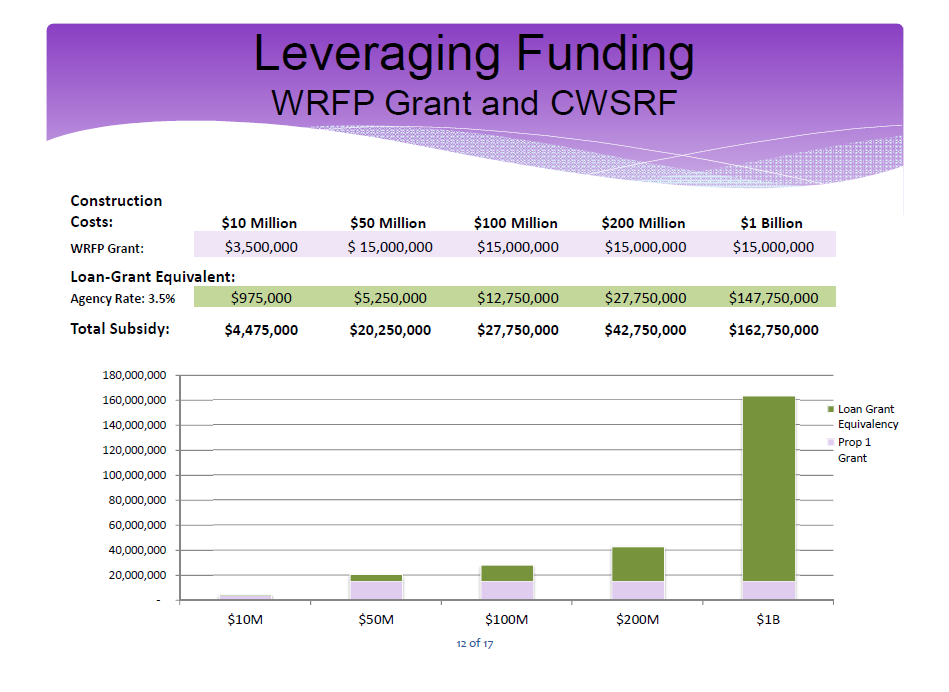

LEVERAGING: One of the interesting aspects of the program is how the grants can be leveraged by joining them with Clean Water State Revolving Fund loans up to certain amounts. (See figure, below).

(Source: SWRCB Presentation, Proposition 1 Recycled Water Funding Workshop.)

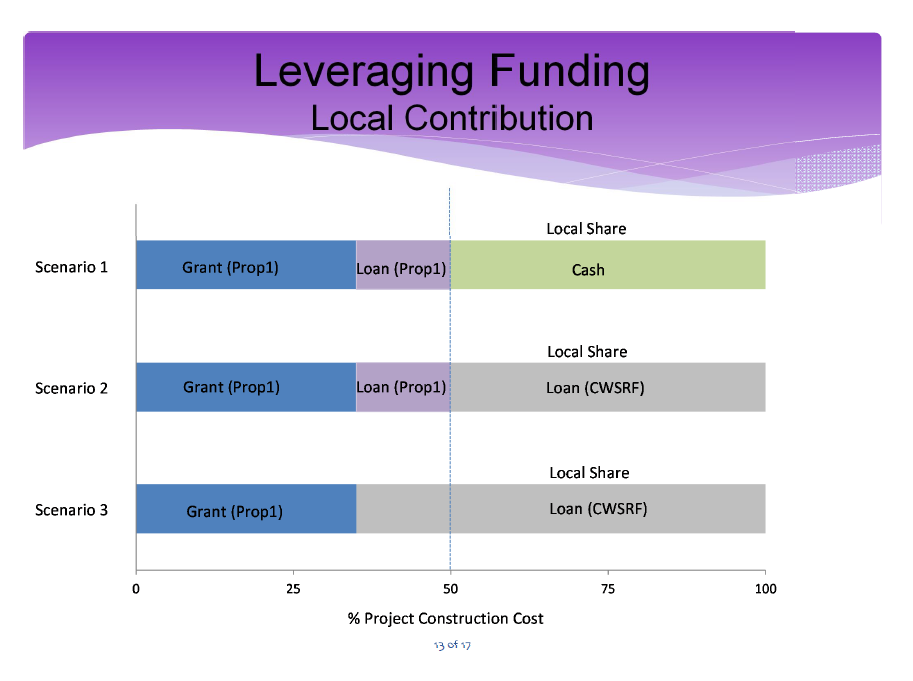

The grants can also be joined with Prop. 1 Water Recycling Fund loans. (See figure, below.)

(Source: SWRCB Presentation, Proposition 1 Recycled Water Funding Workshop.)

The SWRCB presented scenarios explaining that Prop. 1 loans and grants could potentially fund 50 percent of a project, and the State Revolving Fund or other federal funding sources could pick up the remaining local share. There may even be opportunities to co-fund with other sources, such as Department of Water Resources’ Integrated Regional Water Management program if both programs’ requirements can be met.

APPLICATIONS: Although the State Revolving Fund application is known to be rigorous, the convenient aspect is that requests from multiple Division of Financial Assistance sources through the SWRCB can be tapped with a single application and agreement. Also, the SWRCB maintains that a project manager will shepherd each application through the various segments of the process. Due to the complexity, the SWRCB stresses that applicants should get the initial “general application” (see online application here) submitted first in order to contact a project manager for finishing the later application portions and submittal steps. The SWRCB also encourages submitting individual documents as soon as they are available so that the SWRCB can work on reviewing them for each part of the application.

It is important to note that a final project agreement will be executed only after the environmental documentation is finalized, and the environmental review process can take substantial time. The SWRCB noted it has an entire unit dedicated to environmental review, which was doubled in size for administering Prop.1 funds.

The bottom line is that there is no need to have all of the documents submitted as a single package. Instead, start the process early, and get documents in as they become available.

TIMING: Comments on the guidelines are now closed, and the SWRCB’s staff anticipates that revisions to the guidelines will be approved by the SWRCB in June, with financing beginning by July. SWRCB is currently accepting applications, even though funds are not available. To qualify for the current fund allocations, the completed applications must be received by Dec. 2. An initial agreement will be executed to allow covering the soft costs for planning and engineering. Program loan interest rates are locked upon executing the final grant agreement.

[divider] [/divider]

Steven G. Martin is an attorney in Best Best & Krieger’s Special Districts and Environmental Law & Natural Resources practice groups and is based in the firm’s San Diego office. He has assisted public agency clients with a variety of local governance, transactional, and litigation-related matters. He can be reached at steven.martin@bbklaw.com.