By Andrews Keatts.

Brian Catanzaro grew up in Pacific Beach, and he’s stayed there to raise his own family. He lives in a relatively quiet part of the neighborhood near Kate Sessions Elementary, removed from what he called the “drunken stupor” dominating Garnet Avenue.

He’s noticed changes in his longtime home.

It used to be easy to get on the freeway, now it’s not. It used to be easy to catch a wave, now he shares them with dozens of surfers at a time. He used to take quiet walks in Mission Bay park, now it’s full of exercise classes and other commercial activities.

When political leaders implore support for building more homes in San Diego, he scratches his head.

“If it’s bad for me, why should I roll over and say, ‘No, no, no, I want this, even if it’s bad for me?’” he said. “It’s stupid.”

The common response, from politicians and media alike, is that San Diego is destined to grow, no matter what, and we must prepare for it.

One projection guides all of that. The San Diego Association of Governments, or SANDAG, says the region will grow by 1.3 million people by 2050, a 40 percent overall increase from the 2010 Census.

SANDAG’s own blueprint for highways, light rails, bike paths and bus lines through 2050 relies on it. So does the county water board’s 25-year outline of water supplies and demand. The plans cities draw up for their future housing and capital improvement needs, like San Diego’s general plan, do too.

If history is any guide, San Diego’s population will continue to grow. That’s something of a given.

The question is, how much? That’s what SANDAG’s projections seek to answer. They’ve done an especially bad job of it.

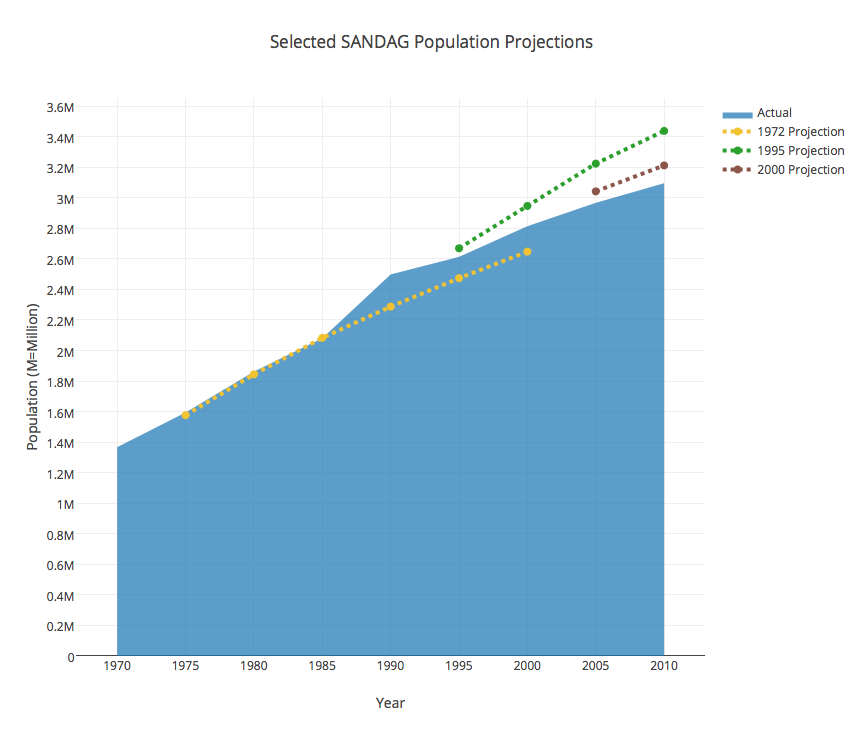

The best that can be said for SANDAG’s projections is that they’ve expected the population to grow, and grow we have.

But they’ve been wildly inaccurate at predicting how much growth would occur. Since 1990, they’ve consistently predicted far more growth than we’ve experienced.

Growth Will Happen

Environmental attorney Marco Gonzalez built a career fighting sprawl in undeveloped areas. Last year he challenged fellow anti-sprawl environmentalists to embrace dense housing as an alternative.

“The first presumption is growth,” he said. “Will growth occur? I think it will. Whether you believe SANDAG’s projections … growth will occur, especially along our coastline, and the question is, what obligation do you have … to accommodate some portion of that growth?”

Gonzalez’s basic claim — like it or not, San Diego will grow — has been unfailingly true. And while SANDAG’s projections underestimated that growth in the 1980s and overestimated it in the 1990s, they have nonetheless accurately predicted continued population increases.

Over the last 40 years, SANDAG’s projections were within 1 percent, on average, of San Diego’s actual population.

Through the 1980s, SANDAG’s projections undershot actual growth by almost 3 percent on average. The projections it has released since 1990 routinely missed the other way. SANDAG overestimated the eventual population by nearly 6 percent in the last 25 years.

At the very least, leaders making decisions informed by these estimates aren’t being led in the wrong direction, said Peter Brownell, research director for local think tank Center for Policy Initiatives.

“The lines are all going in the same direction, right?” he said. “So it’s high by 6 percent: the reality is, it’s not telling us, ‘Oh, we don’t need to add housing, or schools, because we don’t have to expect growth.’”

Where SANDAG’s forecasts strongly diverged from the actual population, it points to major political or economic events — the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, which shifted military spending out of Southern California, or the housing bust and great recession of the 2000s.

“We don’t ever claim to forecast recessions or booms or busts or one-off events,” said Clint Daniels, manager of regional projections for SANDAG. “Over the long term the trend is pretty constant.”

Growth will happen. But knowing that is the easy part.

A Big Forecasting Error

If you compare our actual population to what SANDAG said it would be, the agency looks good.

But there’s another way to measure the forecast’s accuracy. Look at how much growth it said would occur, versus what growth actually occurred. We wouldn’t expect San Diego’s population to fall to 500,000 people in the next 10 years. Nor would we expect it to climb to 10 million people in the same time. The range of reasonable guesses for SANDAG’s projections is actually pretty small. That it can land within 10 percent of the population isn’t surprising.

What policy-makers care about is how many new people they need to accommodate, said Richard Carson, professor of resource economics at UCSD.

“If you’re thinking of building new schools,” Carson said, “you don’t care about the existing population, because they’re already in schools. What you care about is the people who need new schools, about the size of change, because that’s what you need to build new infrastructure for.”

On that count, SANDAG’s projections have been abysmal.

In 2000, for instance, SANDAG projected the region would add nearly 400,000 new people by 2010. Instead, the population grew by just 280,000 people. The agency overestimated actual growth by 43 percent.

In 1990, SANDAG told local governments the region would add 480,000 people by 2000. The region added 315,000. That’s a 52 percent error.

They’ve missed the other way too, though it’s been a while.

In 1980, SANDAG told local governments to prep for an increase of 460,000 new residents by 1990. The region actually added 630,000 people, 27 percent more than SANDAG said.

“One can be completely agnostic about whether the population going up or down is good, but to the extent that our infrastructure budgets are driven by this projected change, along with all the other development policies for cities and the county, that’s a pretty big forecasting error,” Carson said.

Daniels acknowledged this is a legitimate way to measure the success of SANDAG’s projections — and that it makes them look much worse.

But, he still prefers measuring against the total population, because governments aren’t just trying to provide infrastructure for new residents.

“Say no one else moves here and no one else is born,” he said. “Do we all stop paying taxes and stop providing services? Even if the population is stagnant, there’s still demand for new services.”

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Voice of San Diego.

Damon Crockett contributed data analysis for this story.