Builders Like the Campanelli Brothers Helped Fuel Midcentury Suburban Desire, from Massachusetts to Moscow

After V-J Day—August 14, 1945—millions of World War II veterans came home and began to look for a place to live. New highways, cars, and government-sponsored mortgages encouraged them to dream big. Up until that point, Americans, especially immigrant Americans, had thought of the Land of Opportunity as the place where discipline and hard work would guarantee prosperity and upward socialmobility. After the War, they believed they could have more. The American Dream now meant home ownership and spatial mobility, too. Young families emerging from the years of wartime austerity sought dwellings outside traditional city neighborhoods. They wanted a small house in the suburbs.New speculative builders, or “merchant builders” (as they called themselves), responded to answer this desire. In the first two decades after the end of the war, tens of thousands of such builders erected more than 13 million new single-family houses in new suburban subdivisions. These dwellings looked radically different from most buildings of the past: They were low-rise ranch or split-level houses, rather than the two- or two-and-a-half-story blocky-looking structures that had previously dominated suburban landscapes (houses with formal plans, sited on relatively narrow lots).

Old-style suburban house from Authentic Small Houses of the Twenties (1929)

Until recently historians have not known much about these builders. The Levitts, who created three very large developments in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, are well-known—but they weren’t typical. The Levitts built new communities with thousands of dwellings at top speed. The average merchant builder worked more slowly, in much smaller subdivisions, and in varied locations. Merchant builders often shared the backgrounds and attitudes of their buyers.

The Campanelli Brothers in 1948

The Campanelli Brothers of Braintree, Massachusetts, were one of these typical merchant builders. When Michael, Joseph, Nicholas, and Alfred Campanelli created a construction company in the late 1940s, they were young and inexperienced. Their parents, Francesco Campanelli and Lisa Marie Colondono Campanelli, arrived in the U.S. in 1915 from a tiny and ancient mountain village in the Italian Apennines; they settled in an immigrant neighborhood in the small city of Brockton. The boys were used to hard work, quitting school after their father died to help support the family by working at the Quincy shipyards near Weymouth. Joseph also worked on some house construction sites before World War II. The three younger brothers served short stints in the Navy during the war.

After they came home, the brothers used an army surplus truck to move gravel to big construction sites, including Logan Airport. Soon they began pouring concrete footings for new buildings. As their assets increased, they built two new houses in Brockton, one for their mother and one for their sister Ann, whose husband, Salvatore De Marco, now joined the brothers’ team. They branched out to small developments near Braintree, Massachusetts, and Warwick, Rhode Island. Success there led them to develop more ambitious subdivisions in Natick, Framingham, Peabody, and other areas near Boston. In the process, they assembled a sizable group of foremen and loyal subcontractors, many drawn from their old neighborhood and earlier shipbuilding work. Their firm rapidly grew into the leading home building enterprise in the Boston area, and later built extensively in Florida and Illinois as well.

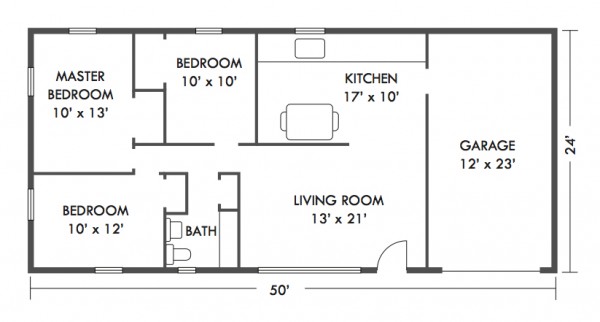

The typical Campanelli house was attractive because, as one buyer explained it, it was “a new kind of house” for “a new time.” It discarded the old-fashioned, larger, more monumental look. It had a low-pitched roof, like contemporary ranch houses in California, but still kept shutters or an occasional bow window for a faintly “colonial” flavor. Campanelli houses usually had two or three bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen large enough to eat in, and a garage. The three-bedroom version was about 1,000 square feet of living space. In the mid-’50s, the firm extended the kitchens to form a “living kitchen” or a kind of a “family room.”

Plan for a typical Campanelli Brothers house

These plans were compact and “open,” with far less division between rooms than had usually been the case in American houses for all classes before World War II. The focus was on informal family activities—reading, watching TV, eating—and on an easy connection between indoors and out. In the rear stood a patio with the family barbecue and a large open yard, inviting for children’s play.

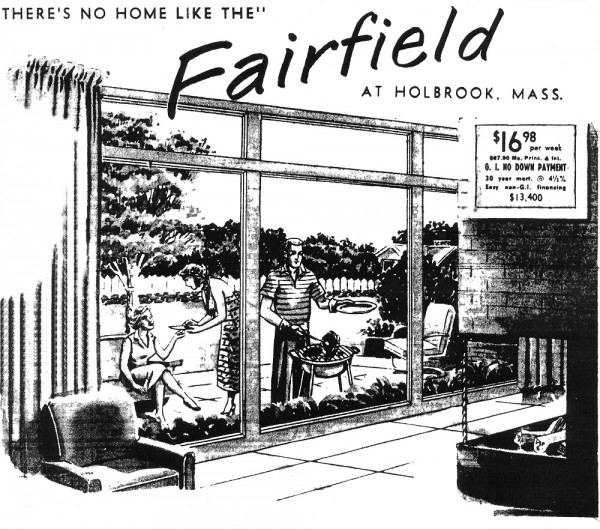

Ad for a Campanelli Brothers house, 1956

In the front, a large “picture window” offered passersby and visitors a preview of the interior. The fenceless and hedge-less front yard ensured visual continuity with neighbors’ houses and the street. Wide roads, with sidewalks, were laid out in curvilinear patterns by the firm’s engineer. The houses were equipped with sophisticated appliances—like the GE wall-mounted refrigerator that the Campanellis often used. Each house had a fireplace.

Ad for a wall-mounted refrigerator, 1956

How did builders arrive at these designs? The Campanellis always insisted that the designs were theirs. Yet they often said, in conversation and newspaper ads, that “the best architects a builder has are today’s home buyers and prospective buyers.” The Campanellis watched sales closely: The firm would begin a subdivision with a few model houses in various styles, and then continue building the model that sold best. What sold, and sold “like hotcakes,” were the new ranch houses.

The typical buyer was in a hurry: Near Boston and in most other American metropolitan areas, new homebuilding had stalled as the country struggled with the Depression and World War II. This meant an acute housing shortage. The typical buyer was eager to get started on a new life with the new family, new job, and access to a Federal Housing Administration—or Veterans Administration—financed mortgage. He and his wife wanted a house that broadcast the idea of “modernity.” They saw the Campanelli ranches as embodying the new lifestyle that they sought.

This ranch house was the type that was shipped to Moscow in 1959 to demonstrate what was available to the “average American.” (It was in the kitchen of a model ranch house that Vice President Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had their famous “kitchen debate” over the relative merits of Soviet communism and American capitalism.) Houses like this embodied the postwar aspiration of home ownership by the nuclear family, access to new places via the automobile, and a new, freer and more informal lifestyle.

In the first 15 to 20 years after the war, the buyers of new houses often came from white working-class backgrounds of varying ethnicities. Because of discriminatory FHA restrictions on mortgages, people of color initially had little access to the new suburbs. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964, however, African-Americans, Asian- Americans and Hispanic-Americans began to transform the population of the early suburbs. Meanwhile, however, rising land prices and rising interest rates began to close the frontiers of new suburbs to working-class populations. New kinds of builders, often large-scale corporations, built on the interstices between the postwar subdivisions—larger and larger houses, with more rooms for more specific purposes, aimed at ever-more-affluent buyers. The family home came to be seen as an investment that would be “traded up.” The postwar suburbs have merged into overall sprawl.

One result of these changes has been the widely disliked, oversized “McMansions” of today; another is the growing tendency of young couples to seek alternative housing: either in smaller and more mobile dwellings within “the tiny house movement” or in non-traditional center-city spaces such as lofts. The McMansions usually imitate monumental house styles of the 19th century, though they retain two features of the houses of the postwar era: the multifunctional living room (now called “the great room”) and the large “living kitchen” invented by the Campanellis and other merchant builders. And they are uncomfortably crowded onto small lots that are descended from the postwar era.

The long-term picture of American suburban housing since 1945 is one of sprawl, stylistic disunity, and diverging social composition. But for a while, merchant builders and postwar buyers created a new and attractive kind of American modernism for American domestic architecture.