At a time when some are calling soaring state and local government pension debt a crisis, there is a notable outlier. The Fresno city pension system has been fully funded for at least a decade and last year projected a $289 million surplus.

The main reason Fresno pensions have remained fully funded: The city’s public employee unions have accepted comparatively low retirement benefits, a particularly important concession by the police and firefighters who are a big part of the budget.

When another Central Valley city, Stockton, declared bankruptcy four years ago city officials said they would not cut the largest debt, a $211 million pension “unfunded liability,” because attractive retirement benefits are needed to remain competitive in the job market.

Stockton’s decision to cut only bond debt, despite a federal judge’s landmark ruling that CalPERS pension debt also can be cut in bankruptcy, was contested by two national bond insurers and a major bondholder, Franklin.

Not having a large pension debt to pay off helped Fresno cope with budget deficits during the recession. Speaking to the Bond Buyer last August, Mayor Ashley Swearengin recalled Time magazine mentioning Fresno as a possible bankruptcy.

Moody’s did not give Fresno bonds a hard-earned upgrade from a junk rating until last summer. Nearly a dozen rounds of painful quarterly budget cuts, begun early in the recession, left Fresno with a depleted workforce as the city struggled to close budge gaps.

“We had 4,100 employees and now we have 3,300,” Swearengin told the Bond Buyer. “Of those jobs, only 200 to 300 were layoffs. The rest were people who left, retired, or positions that had been held vacant, but were funded.”

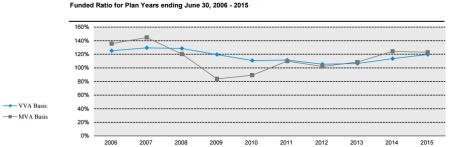

The Fresno pension systems, never falling below 100 percent funded on an actuarial basis, continued receiving required employer-employee contributions during the recession, a timely addition to pension fund investments as the stock market began a major bull run after the bottom in 2009.

“In some people’s minds the city might have landed in bankruptcy if the city management and the unions hadn’t agreed on the incredibly hard step of instituting layoffs and freezes to keep the city functioning,” Robert Theller, Fresno Retirement Systems administrator, said last week.

Theller attributed the fully funded pensions to low payouts, unions that disagree with management on some points but are generally cooperative, good timing on a $152 million pension obligation bond in 2002, and conservative pension boards that invest carefully.

“It’s a well-run ship, and it has been for many decades,” said Theller, one of the reasons he was excited about taking the post last January.

Fresno city pensions can seem at odds with conventional pension wisdom. The investment earnings forecast is 7.5 percent, which critics usually contend is overly optimistic and conceals massive debt.

Recruitment and retention of Fresno city employees is not said to be a serious problem, even though retirement benefits are well below those offered by the Fresno County pension system, deep in debt with a $1 billion unfunded liability.

Like the large coastal cities, Fresno, the largest Central Valley city (estimated 2015 population 520,052, Sacramento 490,712), has independent city and county retirement systems that are not part of CalPERS, the giant California Public Employees Retirement System.

The rare Fresno city pension surplus was reported last March by Robert Fellner of Transparent California, a searchable public data base that lists the pay and pensions of individual state and local government employees and retirees.

Fellner said the average Fresno city pension for a police or firefighter with 30 years of service was $70,627 and the average pension for other (non-safety) 30-year city employees was $39.644.

In comparison, he said, the average Fresno County pension for a non-safety employee with 30 years of service was $61,513, more than 50 percent higher than the pension of a similar city employee.

“Fresno County will spend a staggering 52 percent of pay on retirement benefits, which is over triple the 16 percent rate that Fresno City pays, and over 17 times more than the 3 percent that the median private employer spends on employees’ retirement accounts,” Fellner reported.

The city and county both provided average full-career pensions that exceeded the average pay, $36,975, of private-sector workers in Fresno County, Fellner said, according to 2014 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics.

On the same day last month, Oct. 25, Fellner’s Fresno report wasfeatured on Fox television news, while an academic newsletter distributed a study that found the Fresno County pension system led the nation in eating up county budgets.

The study by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College used its own methodology to compare the percentage of “own-source revenue” (excluding transfers from state or local government) taken by pensions, retiree health care, and debt service.

Fresno County ranked No. 1 (see chart below), in a nationwide sample of 178 counties, with pensions taking 57.1 percent of own-source revenue, retiree health care (OPEB) 0 percent, and debt service 4.5 percent.

In an email response to a request for comment on the study, the Fresno County Employees Retirement Association said it “does not control, create, or negotiate benefit formulas” and “continues to have the ability to provide guaranteed retirement benefits.”

Fresno ranked No. 33 in the study, among a nationwide sample of 173 cities, with pensions taking 8.9 percent of own-source revenue, retiree health 2.2 percent, and debt service 7.1 percent.

The president of the Fresno Police Officers Association, Jacky Parks, said last week the low city pensions have had an impact on recruiting and retention. For example, he said, a “lateral transfer” from an employer in CalPERS can be difficult for several reasons such as differences in “pensionable pay.”

CalPERS sponsored legislation, SB 400 in 1999, that gave the Highway Patrol a “3 at 50” pension formula providing 3 percent of final pay for each year served at age 50, capping the pension at 90 percent of pay.

Critics say the costly “3 at 50” formula, widely adopted by large local governments, is “unsustainable” and a major cause of pension debt. Fresno offers a “2 at 50” formula increasing to 2.7 percent at age 55, capped at 75 percent of pay.

Parks said Fresno also has a DROP plan that allows officers to earn a retirement benefit comparable to the “3 at 50” formula. He said most officers enter the DROP plan at age 50, limiting them to no more than 10 additional years on the job.

(The Deferred Retirement Option Program freezes the pension earned at that point. The pension amount, plus COLAs and interest at a rate approved by the pension board, goes into a special account until the employee leaves the job.)

Parks said Fresno officers are “proud we have a solvent system” and are aware that “everyone is a little worried” about the financial condition of the Fresno County retirement system.

“The philosophy of our (pension) trust is that you need to be financially responsible so this is going to be forever, so the next guy that gets here doesn’t need to worry,” Parks said.