New annual CalPERS reports no longer prominently display the pension debt of local governments as a percentage of pay, making it more difficult for the public to easily see the full employer pension cost.

An example of how the debt can get lost in the shuffle of the new policy happened last month when the California Public Employees Retirement System dropped its long-term earnings forecast from 7.5 percent to 7 percent.

To help fill the funding gap created by lower investment earnings, the annual rates paid to CalPERS by state and local government employers will gradually increase over the next eight years.

A California State Association of Counties report to its members about the new rate increase only included the CalPERS sample of higher employer rates for the “normal cost,” the amount paid for the pension earned during a year.

Not mentioned in the county report was the additional rate increase for the rapidly growing pension debt or “unfunded liability” from previous years, mostly caused by investment earnings (expected to pay two-thirds of future pensions) that were less than the forecast.

For many employers, the current CalPERS rate for the unfunded liability is higher than the rate for the normal cost. The need to pay down the unfunded liability, which grew to $139 billion this year, is the reason for the new round of CalPERS rate increases.

What tends to obscure or mask the debt in the new CalPERS reports is a change in the way rates are set and reported. The “normal cost” rate is still a percentage of pay. But now the unfunded liability rate is a dollar amount.

Instead of a total rate shown as a percentage of pay, a presentation to the CalPERS board last month and a CalPERS news release both showed the average rate increase for employers in two separate parts, each reported in a different way.

The average normal cost rate increase was reported in the traditional way as 1 percent to 3 percent of pay for most miscellaneous employees, 2 percent to 5 percent of pay for safety employees that include police and firefighters.

In addition, the CalPERS news release said, many employers “will see a 30 to 40 percent increase in their current unfunded accrued liability payments.” That’s the new way of reporting the pension debt using a dollar amount, not the percentage of pay.

Getting a total average rate increase by combining the two rates reported in different ways would be difficult. And with no comparison to pay, it’s not easy to see whether an unfunded liability rate shown as a dollar amount is relatively large or small.

The new CalPERS local government reports say the change was made to “address potential funding issues that could arise from a declining payroll or reduction in the number of active members,” leading to the underfunding of some of its more than 2,000 pension plans.

But a skeptic might also wonder if one of the side benefits for CalPERS, as rates paid by employers continue a decade-long rise, is less clarity about the size of the bite that pensions take from government budgets, reducing funding available for basic services.

“It’s all there,” said Wayne Davis, CalPERS public affairs chief. “We’re not trying to hide it.”

Costa Mesa is known for high CalPERS rates, a blocked attempt to outsource services, a fatal jump from the city hall roof by one of the workers facing layo [divider] ffs, and a lawsuit against the police association for conspiring against two pension-reformer councilmen. [/divider]

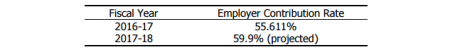

Before the change, the first page of the annual CalPERS valuation report for the Costa Mesa police plan on June 30, 2014, shows the employer contribution set for this fiscal year is 55.6 percent of pay and a projected 59.9 percent of pay next fiscal year.

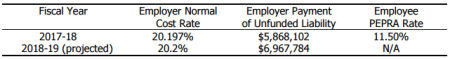

The first page of the new CalPERS report for the Costa Mesa police plan as of June 30, 2015, shows an employer normal cost rate for next fiscal year of 20.2 percent of pay, an unfunded liability payment of $5.9 million, and an employee PEPRA rate of 11.5 percent.

If readers of the report didn’t know that CalPERS values transparency (see Pension and Investment Beliefs No. 8), they might suspect that the new report is intended, when given only a glance, to understate the total pension cost, while suggesting that employees pay half of it.

The PEPRA rate is paid by new employees hired after Jan. 1, 2013, when the Public Employees Pension Reform Act took effect. The rate paid by employees hired before PEPRA is 2 percent to 8 percent for miscellaneous, 7 percent to 9 percent for police and firefighters.

The decision to display only a smaller and less-alarming part of the rate in the new Costa Mesa valuation was not because the total wasn’t calculated. It’s in the report, shown as a percentage of pay. But it’s buried in the second of two small-print footnotes at the bottom of page 4.

Reporting pension costs as a percentage of pay is traditional for a reason: It makes costs easy to understand and compare. For example, the average employer contribution to the 401(k) retirement plans now common in the private sector is 3 percent of pay.

The average local government employer contribution to CalPERS for police and firefighter pension plans last year was 40 percent of pay and for the miscellaneous plans covering most employees 21 percent of pay.

Switching the rate for the unfunded liability to a dollar amount was a response to PEPRA changes that, among other things, allowed the debt payments for pooled and non-pooled plans to be “consistent” and expressed in the same way.

“This change has been discussed with employers numerous times, including the last two Educational Forums, and appears to be widely accepted by employers,” a staff report to the CalPERS board said last April.

There appears to be no reason that CalPERS, while continuing to set unfunded liability rates in dollar amounts, could not resume reporting total rates as a percentage of pay in news releases and the face pages of valuation reports, unfogging the window of transparency.

[divider] [/divider]