Staff members then prepared a presentation describing the errors they had discovered, and the dramatic implications they carried for the regional planning agency.

After receiving the presentation, SANDAG’s executive director and other high-ranking officials did nothing. They didn’t pass the information to the agency’s board of directors, composed of elected officials from around the county. They didn’t alert the oversight committee created specifically to make sure a tax-and-spending program approved by voters in 2004 was making good on its promises.

Instead, the agency continued to rely on the forecast it had been told was faulty, misleading voters in the process and keeping important information from potential watchdogs.

Four months after receiving the staff presentation, SANDAG approved putting a tax measure on the ballot that promised to raise $18 billion for transportation projects. That total relied on the forecast that officials had already been told had major problems.

Likewise, officials did not use the new information to adjust their plans for TransNet, the tax voters approved in 2004 to fund regional transportation projects. Nowhere in TransNet’s plan of finance or in documents given to that measure’s oversight committee did SANDAG acknowledge that its own modeling team and chief economist had discovered the spending total approved by voters – and therefore the list of projects promised to voters – was no longer realistic.

Voters rejected Measure A. If it had passed, SANDAG would have been able to use the new money to plug TransNet’s shortfall. Now, the agency has disclosed it has a funding shortfall of billions of dollars and no clear way to address it. The agency is already discussing another potential tax hike.

In an interview, the agency’s director and chief deputy director acknowledged that they did not act on the information presented to them in any way, or alert the board of directors or watchdog group to the new information. They said they instead planned to make the necessary changes when they were scheduled to next adopt a new forecast.

In the meantime, though, they asked voters to approve a tax measure that they knew was based on bad, and potentially outright false, information. The overstated revenue total, whether or not it was intentional, allowed the agency to build a larger project list, which would appeal to more voters by offering projects that might entice them directly.

Voice of San Diego revealed the problems with SANDAG’s forecast in October, weeks before voters weighed in on the measure. The agency insisted at the time that it was still on track to build everything it had promised voters in 2004 with TransNet and that the new tax hike, Measure A, would raise as much as they were telling voters.

They’ve since acknowledged the measure wouldn’t have generated $18 billion. But it turns out they not only knew that in November – they knew it nearly a full year earlier, and months before they finalized the measure that went before voters.

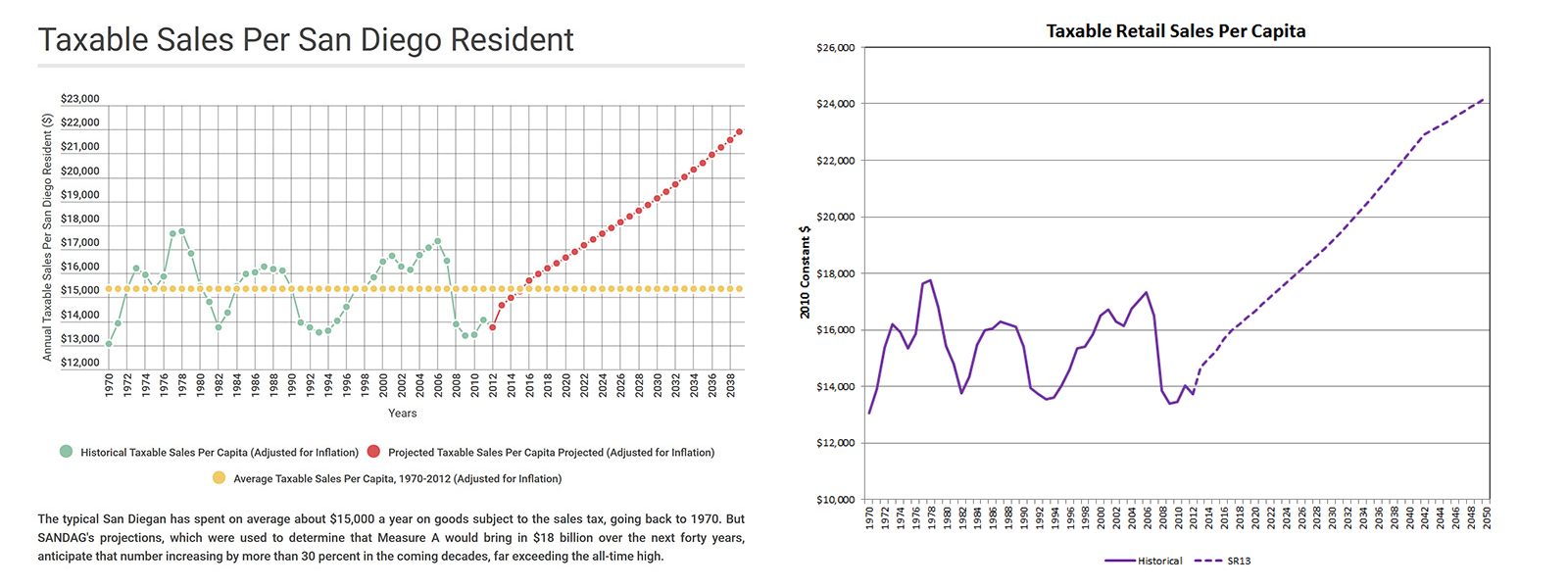

In November 2015, Dmitry Messen, a modeling staffer at SANDAG, sent Major a chart demonstrating how much the typical San Diego resident had spent on taxable items in the county going back to 1970, and how SANDAG’s long-term forecast expected that to change in the future.

In a series of emails, Major eventually recognized there was a big problem. He asked Messen to confirm that he understood the situation accurately: Is it really true, he asked, that taxable sales had historically increased by just .69 percent each year on average, and yet the agency’s forecast was expecting them to grow by 1.3 percent annually in the future?

Yes, Messen said. That’s correct.

That’s when Major responded: “Omg.”

“I can think of another popular 3 letter acronym,” Messen said in an email.

“Wtf,” Major concluded.

The next month, Major and other modelers put together two presentations for SANDAG officials, emails show. One was about why the agency’s projections for income and taxable sales were so high. The other was simply titled “Presentation for Executive Team.”

Together, the presentations paint a clear picture: SANDAG’s forecasts have indefensible expectations for how rich San Diegans will become in the coming years, thus creating unsustainable expectations for how much money everyone will spend. That has translated into unreasonable revenue expectations for the agency’s spending programs.

In April, four months after SANDAG executives learned of the problems with the revenue forecast, the agency’s board of directors approved putting the $18 billion spending plan before voters.

One slide in the presentation specifically shows that a more reasonable set of expectations would mean TransNet would collect much less money. The agency also creates a spending plan based on just the next few years, instead of the full 40-year period of the tax, and the presentation showed that too was expecting too much money.

Yet SANDAG never explicitly disclosed these findings anywhere. In fact, in a report to TransNet’s oversight board this summer, SANDAG provided a lengthy explanation for why it was not concerning that the agency had collected much less money than anticipated. That explanation was written nine months after SANDAG staff discovered that its forecast wasn’t reliable, but contained no mention of that discovery.

Emails show that explanation was written by the agency’s former chief economist, Marney Cox.

“Marney did the calculations and wrote the paragraph below. It was his model,” Major wrote to another staffer, of the explanation that was eventually provided to the oversight board.

The agency’s director and chief deputy director, Gary Gallegos and Kim Kawada, said they did not act on any of the information presented to them about their forecast because Cox argued that though the projections were aggressive, they were not impossible.

Gallegos and Kawada also said the connection between forecasting taxable retail sales and the revenue they could generate from a tax measure was not immediately clear – even though the faulty forecast’s impacts on TransNet revenue was specifically spelled out in the report provided to them.

That’s why the $18 billion projection for the tax measure that became Measure A was never amended and the agency presented the number to voters despite concerns from SANDAG’s own internal experts.

“I hear what you’re saying, in terms of how the optics look, but I don’t think it’s that,” Kawada told me. “The mistake was we relied on our longtime economist to give us our revenue projections for Measure A. It wasn’t until we sat down with Ray Major, as the new chief economist coming in with fresh eyes, going ‘Hey this doesn’t make sense.’”

“Marney probably thought until the end that we were going to get those dollars,” Gallegos said.

Kawada and Gallegos said SANDAG officials were going to make changes the next time they updated the forecast but were jolted into action earlier than planned when Voice of San Diego published its investigation into the revenue problems facing both TransNet and Measure A.

“Once we realized what (Voice of San Diego) highlighted … we started bringing people together and forcing that conversation,” Gallegos said. “It was a pretty intensive month and a half look at people trying to figure out what’s causing this.”

Why did it take a reporter presenting the information to spur action when their own staff members had alerted them to the problem a year earlier?

“It really was, to be honest with you, I know you said, ‘I’m not an economist, I’m a layperson’ but it took [the Voice of San Diego investigation] for us to go, ‘OK guys, if you’ve told us this, then we need to take a time out, stop everything,’” Kawada said.

This ignores, however, that the second slide in the presentation included a chart that is virtually identical to one published by Voice of San Diego before November’s election, which uncovered that the ballot measure would be hard-pressed to raise the $18 billion it was promising voters.

The chart shows how much people would have to buy in San Diego over coming decades to to make good on the projection that the tax on purchases would raise $18 billion.

“Very hard to explain this one,” read a note appended to the slide in the presentation.

SANDAG leaders saw this chart twice. It was only when it was reported publicly did the agency react to it in any way.

The revenue total on the ballot is important because it is used to derive the list of projects promised to voters. That list is politically crucial, because the measure needs to win the support of special interest groups and elected officials with disparate concerns, each jockeying to ensure the measure achieves their priorities. It’s crucial on the ballot, too, since polling data shows voters tend to look at the list to ensure there are projects that will ease their commute or that correspond to their priorities.

After Voice of San Diego’s October investigation, SANDAG had its modeling, demographics and economics staffers working almost entirely on identifying and fixing the problem. It took a month and a half, and the agency then disclosed in vague terms that they indeed had a revenue problem.

It has since adopted a new forecast – derived by averaging three national forecasts from third-party agencies – which significantly curtailed revenue expectations. The new forecast means TransNet could raise $4 billion less than voters were told in 2004.