CalPERS needs the high yields from private equity to help hit its long-term earnings target. But some firms have rejected or limited CalPERS investments, saying the big pension system has become unpredictable and difficult to work with.

A quarter century ago CalPERS was one of the first pension funds to invest in private equity as an alternative to stocks, bonds, and cash. Most big profits come from sometimes controversial “leveraged buyouts,” borrowing to buy, restructure, and then sell companies.

Other private equity strategies promote long-term company growth and provide venture capital to startups. A “fund of funds” provides diversity and spreads risk by investing in a number of private equity funds.

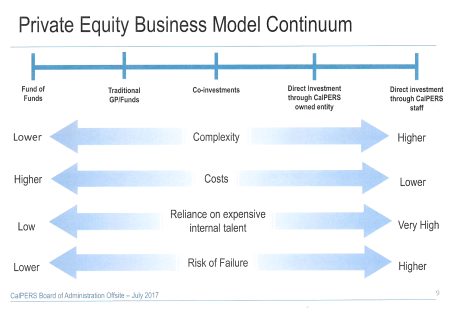

Now CalPERS is considering adding to its traditional private equity funds, which charge high fees and reap large profits, by reducing fees through co-investments with private equity firms and making direct investments through its own private equity company and staff.

At a meeting in Monterey last week, the CalPERS board was told that during a nine-month “listening tour” staff members sought the advice of 50 accomplished experts from private equity, Wall Street, business, and academia.

John Cole, CalPERS investment director, told the board an analysis of CalPERS strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats commissioned four months ago from Hamilton Lane, a private equity firm, found some strengths but also serious weaknesses.

“Our brand is a weakness,” he said, “because we are often judged to be difficult to work with, often unpredictable in our commitments, inconsistent in messaging partners, questioned about our ability to make timely decisions — all of which have contributed to CalPERS being excluded or curtailed from investment opportunities with a number of very successful potential partners.”

When Cole returned to the point later in his presentation, he mentioned “general partners,” the private equity firm, for example, that buys, manages, and sells the company in a leveraged buyout. An investor like CalPERS could be one of many “limited partners” with only a passive role.

“A number of successful GPs have told us that we have become too unpredictable to do business with,” Cole said, “and many larger GPs are cutting back the amount they are willing to allocate to us within their new funds.”

No firm names or estimates of potential earnings were mentioned. On the listening tour, Cole said the CalSTRS staff heard that high fees and the large gap between high performing and low performing private equity firms are expected to continue.

Many institutional investors are seeking co-investments with general partners as a way to reduce overall fee averages. The competition and overcrowding may raise the potential for choosing investments that turn out to have lower returns and higher risks.

In private equity generally, Cole said: “It is clearly a seller’s market, with the best GPs having an abundance of capital available to them, thereby shifting the negotiating leverage strongly in their favor.”

The number of publicly traded U.S. companies listed on stock markets fell from 7,300 to 3,700 over the last two decades, Cole said. Some choose to go private, avoiding regulations and activist shareholders, and more young companies are choosing to remain private.

When CalPERS investments earned 11.2 percent in the fiscal year ending June 30, exceeding the 7 percent target and boosting the funding level from 65 to 68 percent, publicly traded stocks were more profitable than private equity.

But private equity has on average been more profitable over recent decades, and the trend is expected to continue. In new 10-year CalPERS capital market asumptions, only private equity, with a return of 8.3 percent, is projected to exceed the 7 percent target.

Cole said CalPERS staff believes a combination of all of the private equity models, from fund of funds to direct investing, are required for the “robust and scalable presence” needed to achieve the earnings target.

“Today, our private equity exposure includes $26 billion invested and $14 billion in unfunded commitments across 347 managers, with 92 being direct relationships with managers, and the rest are managers within fund of funds,” Cole said.

Private equity is about 8 percent of the total California Public Employees Retirement System investment fund, valued at $328.4 billion last week.

Fees paid private equity firms have been notoriously high, traditionally “2 and 20” with a 2 percent management fee and a 20 percent share of the profit after earnings reach a basic amount. It’s been a lingering issue for CalPERS.

Two years ago CalPERS launched what it said was an industry-leading data system for reporting private equity fees, four years in development. But much of the national media spotlight two years ago was on the inability of CalPERS to track private equity fees.

Board member J.J. Jelincic got into a well-publicized dispute with the CalPERS private equity staff leader, Real Desrochers, who made one erroneous reply corrected later. Desrochers left CalPERS last April to take a position with a large overseas bank.

Last month, Ted Eliopoulos, CalPERS chief investment officer, told the investment committee that constant criticism of the private equity program, arguably the most transparent among large investors, is harming the CalPERS brand and staff.

“Over the course of the past two years, and frequently in these monthly investment meetings, CalPERS staff is attacked and denigrated for our decision to invest in these funds and for the manner and transparency of our reporting of the fees, carried interest, and expenses attached to those funds,” said Eliopoulos.

Despite support from the CalPERS board and a hard-working staff, said Eliopoulos, “the particular public nature and fishbowl of CalPERS may have reached a tipping point for us in private equity.”

He said if a better solution is not found at the July meeting, CalPERS should consider a reduction in private equity as the investment portfolio is reallocated next year. The investment committee applauded his remarks.

In Monterey last week, the CalPERS board heard from a panel of private equity executives and seemed interested in new private equity models. Like the iconic investor Warren Buffett, CalPERS could become a long-term owner of companies.

A separate company created by CalPERS, with its own board free of civil service restrictions, could pay high salaries for the top talent and skill needed to identify and manage promising direct investments.

Eliopoulos was given approval to return in six months with a proposal for a long-term private equity strategy, which CalPERS has lacked. The current private equity models apparently would remain the cornerstone as CalPERS begins with small steps on new models that could take years to mature.

Meanwhile, some may wonder if the private equity firms that shun an “unpredictable” CalPERS are referring to lower fees re-negotiated by CalPERS after a pay-to-play private equity scandal erupted in 2009.

A former CalPERS board member, Alfred Villalobos, who collected about $50 million in “placement” fees from firms seeking CalPERS investments, apparently committed suicide in January 2015 shortly before his trial was to begin.

His inside man, Fred Buenrostro, a former CalPERS board member who became the CalPERS chief executive, was sentenced in May last year to 4 1/2 years in federal prison after pleading guilty to bribery-related charges.

[divider] [/divider]