Though facing a huge funding shortfall, the CalPERS board yesterday adopted a new plan for its $346 billion investment portfolio that will not bring in more money from another employer rate increase or a shift to riskier but higher-yielding investments.

CalPERS did not recover from an investment loss of about $100 billion a decade ago. It still has only 68 percent of the projected assets needed to pay future pensions, little changed from a low of 61 percent in 2009 despite a lengthy bull market.

Getting more money from another rate increase would be painful. Cities and other local governments warn that four employer rate increases in the last five years are already causing service cuts, staff reductions, pay cuts, and proposed tax increases.

Last December CalPERS lowered its investment earnings forecast used to discount future pension costs from 7.5 to 7 percent. To replace the lower expected earnings, local government rate increases begin next year and slowly increase until 2024.

Seeking higher returns would reverse a CalPERS shift in September last year to lower-yielding investments, reducing the risk of major losses in a downturn. Experts warn that if funding drops below 50 percent, recovery will be difficult if not impossible.

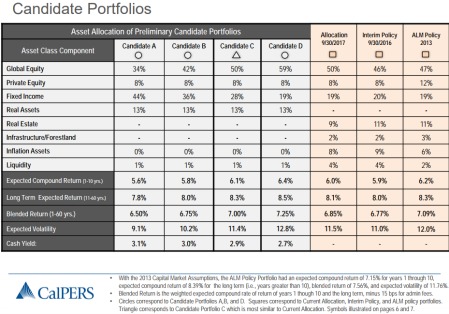

After a lengthy review done very four years, the investment plan chosen by the board (portfolio C in chart below) was not a surprise. The earnings forecast remains at 7 percent, with no need for an increase in rates or investment risk.

Board member J.J. Jelincic received no second for a motion to adopt portfolio D with a 7.25 percent return, potentially giving employers some rate relief. He said the shift to a lower-yielding portfolio last year has cost CalPERS about $2 billion so far.

“Our biggest advantage is that we can be a long-term investor,” Jelincic said. “We are not going to miss payments over the next four, five, six years — so we can accept the ups and downs.”

Board member Richard Costigan, who did not vote “no” on portfolio C like Jelincic, also said he was concerned that CalPERS will be “leaving money on the table” if the market continues to grow for several years as some predict.

“We are 68 percent funded,” said board member Bill Slaton. “If we were 80 percent funded, 85 percent funded then I think our ability to take that volatility into account by having a higher (discount) rate would potentially be acceptable.”

Board member Dana Hollinger, agreeing with Slaton, said with a funding level of 68 percent CalPERS “cannot afford to be wrong” and should adopt an investment plan to protect against the “downside.”

Board member Theresa Taylor said she has changed her view since opposing the shift to lower-yielding investments last year because of the increased cost to employers and post-reform employees.

“I was definitely not on board,” Taylor said, “but I do see that it’s cyclical.”

Henry Jones, the chairman of the investment committee that adopted the plan, said he agrees with the comments that the “sustainability” of the CalPERS fund is a priority.

“I think under different situations when we were more fully funded I would also be willing to take that risk,” said Jones. “But I agree with my colleagues that the risk level would be too great compared to our current rate.”

None of the board members mentioned the two candidate portfolios, A and B, that would have dropped the investment earnings forecast to 6.75 or 6.5 percent, presumably triggering a fifth employer rate increase.

As if to show the difficulty of increasing the funding level, a new CalPERS annual financial report issued this month shows that investment earnings during the fiscal year that ended last June 30 earned 11.2 percent or $24 billion.

That’s well above the expected 7 percent average return. But the funding level June 30 was an estimated 68 percent, down slightly from 68.3 percent at the end of June last year.

The new report said the well-above target investment earnings last year were offset by the CalPERS decision last December to lower the earnings forecast from 7.5 to 7 percent.

Another difficulty is that CalPERS is a maturing pension system in which retirees will soon outnumber active workers.

While strong investment earnings yielded $24 billion last fiscal year, the new report said CalPERS paid $21.4 billion to nearly 670,000 retirees and beneficiaries, up from $20.3 billion to 650,000 the previous fiscal year.

Employers contributed $12.4 billion to CalPERS last fiscal year, up 13.2 percent from $10.9 billion the previous year, the report said. Employees contributed $4.2 billion, up 1.4 to 1.9 percent from $4 billion.

Only the employers, whose rates are set by CalPERS, pay off the debt or “unfunded liability” from below-target investment earnings and actuaral changes. Employee rates, except for new hires after a 2012 reform, are bargained and set by statute.

The CalPERS unfunded liability in the new report is $138.6 billion for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2016, up from $111.3 billion the previous year. ( see chart below) Some estimate that the unfunded liability grew to roughly $153 billion last fiscal year.

Another funding difficulty for maturing systems: The investment fund becomes much larger than the employer payroll, requiring a bigger percentage of pay to replace a loss than when the payroll and the investment were roughly the same size.

The failure of the CalPERS funding level to recover after the huge loss a decade ago is sometimes attributed to a number of factors. CalPERS-sponsored legislation, SB 400 in 1999, led to a generous police and firefighter pension formula critics say is “unsustainable.”

Employer contributions were dropped to near zero around 2000 when CalPERS had a surplus. Some point to divestment from tobacco and other controversial business sectors and investment screens for “environmental, social and governnance” goals.

Bad investment decisions were made by CalPERS, notably in real estate. In 2011, for example, Wilshire consultants ranked CalPERS investment earnings dead last among large public pension funds for the previous five years.

An unusual CalPERS actuarial policy delays debt payment, allowing interest costs to grow. While slowly paying off debt over 30 years, reduction of the original debt does not begin until year 18, more than halfway through the payment period.

And pension funds in general have at least one structural problem. “The solvency of many life insurance companies and pension funds is threatened by a prolonged period of low interest rates,” the International Monetary Fund said in a report last year.

A Milliman report issued this month said the aggregate funded status of the largest 100 U.S. public pensions was 71.6 percent as of Sept. 30, not much better than the estimated CalPERS funding level of 68 percent on June 30.

[divider] [/divider]