Most large private-sector companies and some government employers do not provide retiree health care. But state workers not only get state-paid health care in retirement, they often pay less for it than they did while working.

On the job, the state usually pays 80 percent of the average worker health care premium. The state pays 100 percent of the average retiree premium and 90 percent for dependents, if the worker had 20 years or more of service.

Since most state workers can retire at age 50, the current state retiree premium payment of $21,456 a year for a family of three or more is a particularly good deal for those who choose early retirement.

Now as Gov. Brown leaves office, ending what he called the “anomaly” of retirees paying less for health care than current workers is part of one of his accomplishments — state worker retiree health care reform that had been delayed for decades.

Retiree health care, part of Brown’s 12-point pension reform, was not included in his pension reform bill that, for new hires, extends retirement ages and makes employees pay more for their pensions.

As a legislative analysis of the pension bill said, unions had “shown a willingness” to bargain the issue. Like the pension reforms, three of the retiree health care reforms bargained by the Brown administration only apply to new hires, reducing the amount of the savings.

The retiree health care premium payment is the same as the active worker payment. The state no longer pays for Medicare Part B. And five more years of service are needed to receive state payment of retiree health care premiums, beginning with 50 percent after 15 years and increasing 5 percent a year to 100 percent after 25 years.

After difficult bargaining eased by offsetting pay raises, the major part of Brown’s retiree health care reform applies to workers hired before the reform, not just new hires. All workers are beginning to contribute to a pension-like investment fund to help pay future retiree health care costs.

Lawmakers have known for decades that generous retiree health care should be “prefunded” to cut costs and reduce debt pushed to future generations, who didn’t receive the services of the retirees.

The California Public Employees Retirement System expects investments to pay about two-thirds of future pension costs. The No. 1 recommendation of former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s public retirement commission in 2008 was prefund retiree health care.

In 1991 legislation by former Assemblyman Dave Elder, D-Long Beach, (AB 1104) created a fund in the state treasurer’s office to begin prefunding state worker retire health care. But lawmakers never put money in the fund.

Meanwhile, state worker retiree health care debt soared to $91.5 billion as of June 30, 2017, state Controller Betty Yee reported last January. By comparison, in the latest CalPERS report state worker pension debt was $59.5 billion as of June 30, 2016.

Part of the difference is that Yee’s report, following new government accounting standards, uses a lower investment earnings forecast to discount debt, ranging from 3.56 to 4.22 percent. The CalPERS discount rate is about 7 percent.

The state retiree health care payment this fiscal year is $2.2 billion, up five-fold from $458 million in 2001. The current payment is about 1.7 percent of the state general fund, up from less than a half of one percent 15 years ago.

Prefunding of retiree health care was not in Brown’s 12-point pension reform plan released in October 2011. He unveiled his prefunding plan as he presented the annual state budget in January 2015.

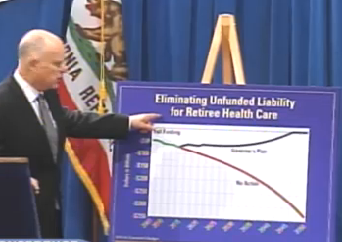

The governor pointed to a chart showing retiree health care debt at a crossroads. If no action is taken, the debt by 2047-48 grows to $300 billion. Under his plan, the debt by 2044-45 drops to zero.

Now all 21 state worker bargaining units, matched dollar-for-dollar by the state, have agreed to contribute to a pension-like retiree health care investment trust fund expected to have $1.6 billion by the end of this fiscal year.

The plan calls for workers to contribute half of the “normal” cost of their retiree health care, an amount large enough to pay for the retiree health care earned during a year, excluding the debt owed from previous years.

A chart (see below) in a Finance department summary of the state budget enacted last June shows the trust fund is expected to have enough money to pay off the retiree health care debt by roughly 2045.

Then the trust fund, rather than the state general fund, begins to pay the annual cost of providing retiree health care for state workers, as shown on the chart by the sharp plunge in cost.

Until roughly 2045, the state continues pay-as-you go funding of retiree health care. And as the chart shows, state costs are higher than pay-as-you-go for about three decades because of the matching payment for state worker contributions.

Some prefunding of retiree health care began in 2010, a year before Brown took office. One of the leaders was the Highway Patrol union, which also bargained an often-criticized large pension increase (SB 400 in 1999) widely adopted by local police and firefighters.

When fully phased in by July 1, 2020, the 21 state worker bargaining units will be paying a wide range of contributions to the retiree health care trust fund, according to a list provided by the Human Resources department.

The nine SEIU bargaining units will be contributing 3.5 percent of pay. The craft and maintenance unit will be making the highest contribution, 4.6 percent of pay; the physicians, dentists and podiatrists unit the lowest, 1.4 percent of pay, and the Highway Patrol 3.9 percent.

The Highway Patrol also is the only bargaining unit that has not agreed to add five more years of service to become eligible for 50 percent state payment of premiums (up from 10 to 15 years) and in 5 percent annual steps reach the maximum payment (up from 20 to 25 years).

Worker contributions to the retiree health care trust fund are not refundable. So new state workers who leave before serving at least 15 years get nothing for their contributions, unless it becomes an incentive to stay on the job.

The “anomaly” of retirees receiving a larger state health care premium payment than active workers is said by some to have a resulted from a cost-cutting move by the administration of former Gov. Pete Wilson in the early 1990s.

Active workers were required to begin paying some of the cost of their health care. No change was made for retiree health care.

Teachers are among the government workers that lack the generous retiree health care received by state workers.

A California State Teachers Retirement System survey in 2011-12 found 11 percent of teachers had no employer retiree health care, 49 percent had some retiree premium support until age 65 and Medicare eligibility, and 29 percent had lifetime employer health care support.

“Postretirement premium support varies by hire date and is decreasing,” said the CalSTRS study.

A Kaiser foundation survey two years ago found a sharp decrease in retiree health care provided by large private-sector companies. Among those with health care benefits for active workers, 66 percent provided retiree health benefits in 1988 and only 25 percent in 2017.

[divider] [/divider]