By Ed Mendel.

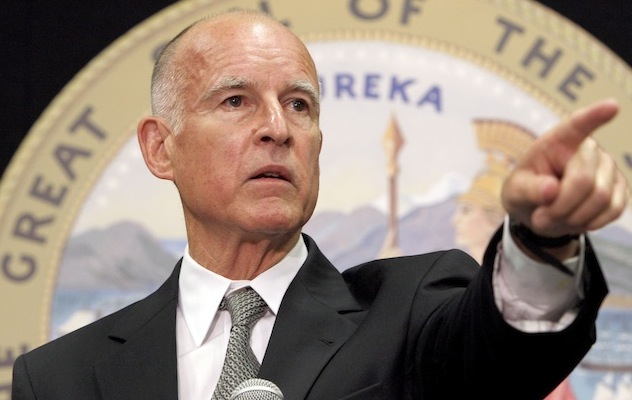

Gov. Brown leaves office next week with a smaller cost-cutting pension reform than he wanted. But after he’s gone, union challenges to minor parts of his reform pending in the state Supreme Court may open the door to big changes.

The main parts of Brown’s reform add several years to retirement ages and make some employees pay more for their pensions. The changes are limited to employees hired after the legislation took effect on Jan. 1, 2013, and the cost savings are modest.

A key part of the Brown 12-point reform, opposed by unions, did not get legislative support. New hires would have been switched to a “hybrid” combining a small pension with a 401(k)-style individual investment plan, similar to a reform for federal employees in 1986.

Union lawsuits, however, led to what a bipartisan watchdog, the Little Hoover Commision, and reformers such as former San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed advocate but have not been able to attain.

The Supreme Court may now review the “California Rule,” a series of state court decisions saying the pension offered at hire becomes a vested right, protected by contract law, that can’t be cut unless offset by a comparable new benefit, thus erasing any cost savings.

What’s needed, say the reformers, is a change in the rigid California Rule that would allow major cost control, such as protecting pension amounts already earned on the job while cutting all pensions earned in the future, not just those of new hires who have no vested rights.

The California Rule presumably is the reason the main parts of Brown’s reform are limited to new hires, reducing the savings. Courts cited the rule when overturning part or all of voter-approved pension cost cuts in San Jose, San Francisco, and Pacific Grove.

Now as pension funding has not recovered from huge investment losses a decade ago — despite a record bull market and a doubling of rates paid by employers — more losses in a looming downturn could add to pension debt and lead to even higher employer rates.

Reformers argue soaring pension costs will continue to eat up budgets, reduce services, raise taxes, and lead to insolvencies and crippled pension systems. Unions say Brown’s reform and contract bargaining allow enough flexibility to ride out long-term economic cycles.

For whatever reason, Brown’s reform included pre-reform employees in two curbs on pension boosts — buying additional years of service, called “airtime” because no work is performed, and using various add-ons to “spike” the final pay on which pensions are based.

If the Supreme Court overturns the two curbs on pension boosts, the reform loses a relatively small amount of cost savings. But the unions, suing to hold on to fringe benefits, took a much bigger risk by contending the California Rule had been violated.

In a groundbreaking ruling, a three-justice appellate panel unanimously ruled in a Marin County spiking case in August 2016 that employees only have a vested right to a “reasonable” pension, not the one offered at hire as prescribed by the California Rule.

Another appellate panel, in an airtime case in December 2016, uanimously agreed with the Marin ruling that employees only have a vested right to a “reasonable” pension, which can be cut without providing a comparable new benefit.

Brown had his attorneys replace the attorney general to defend his reform when the airtime case, filed by Cal Fire Local 2881, became the first of five similar cases to be considered by the Supreme Court.

After extensive briefs in the high-profile airtime case filed by both parties and a number of others, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments early this month. The court has at least two options as it prepares to issue a ruling.

1) Find that airtime was not a vested right and move on to the other challenges to the reform. 2) Make a broad ruling that includes the California Rule and that also applies to the remaining reform cases.

Brown told reporters last January he has a “hunch” the courts will modify the “California rule,” so “when the next recession comes around the governors will have the option of considering pension cutbacks for the first time.”

Part of his reasoning: “There’s already been several lower court opinions through the court of appeals where judges, both liberal and conservative, have taken a position that employees are entitled to a reasonable pension but not entitled to any remuneration they can imagine.”

Brown told the Sacramento Bee this month that without the ability to modify pension benefits, some adopted without fully accounting for cost, employee wages could be suppressed and government services jeopardized.

“If we do it right, people who have a pension and what they’ve earned will never be changed. But you can’t say that five minutes after you sign your employment application, for the next 30 or 35 years that not one benefit can be changed. That’s a one-way ratchet to fiscal oblivion,” he said.

Brown’s Public Employees Pension Reform Act (PEPRA) applies to CalPERS, CalSTRS, and the 20 county systems operating under a 1937 act, but not to UC and the six largest cities that have their own retirement systems.

The California Public Employees Retirement System, covering half of non-federal goverment employees in California, expects the reform to save $29 billion to $38 billion over 30 years, a small reduction in a $139 billion debt or “unfunded liability” as of June 30, 2017.

The lower pension formulas cut costs by requiring employees hired after the reform took effect on Jan 1, 2013, to work several years longer to receive a pension similar to those hired before the reform.

A pension formula bargained by the Highway Patrol often criticized as being too costly, and later widely adopted by local police and firefighters, can provide a pension of 90 percent of final pay at age 50 after 30 years of service.

Its PEPRA replacement provides a pension of 60 percent of final pay at age 50 after 30 years of pay. But the new formula is uncapped and will provide a pension of 108 percent of final pay at age 57 or above after working 40 years, extremely long for physical safety work.

The reform requires new employees to pay half of the “normal” cost of the pension, the amount earned during a year excluding the debt or “unfunded liability” for previous years. But only the employer pays the debt, which ballooned after the financial crisis a decade ago.

A typical police or firefighter pays a rate of 10 to 15 percent of pay. A CalPERS risks report last month said the average safety rate paid by employers will be 50 percent of pay next fiscal year, and 24 local governments will pay 70 percent or more.

The reform caps total pensions for new hires, eventually ending pensions that soared above $500,000 a year in at least two well-publicized cases. Transparent California reported the highest CalPERS pension last year was $378,118 for a Solano County exectuvive.

The final pay used to calculate new hire pensions is linked to the maximum wage subject to a Social Security deduction. In 2018 for PEPRA members it’s $121,388 for employees in Social Security and $145,666 for employees not in Social Security, CalPERS said.

The reform has many provisions, in addition to the airtime ban and a list of anti-spiking pay add-ons, such as a prohibtion on retroactive pension increases, limits on the double-dipping collection of pensions and pay, and using a three-year average rather than one year for final pay.

Getting any pension reform through the Legislature is not easy. Brown was aided by the argument that passage of a tax increase on the November 2012 ballot would be helped if reform gave voters some assurance the new money would not be eaten up by pensions.

Former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger had a record 100-day budget deadlock in 2010 to get Democratic legislators to agree to his modest pension reform. Then on the last night Republicans he said were allies of the prison guard union balked.

They had to go to the home of former Secretary of State Debra Bowen at 3 a.m. to get her signature for a special session allowing the pension bill to pass on a majority rather than a two-thirds vote.

When Brown was running for governor in 2010, he recalled that his last budget during the final year of his previous two terms as governor, 1982, called for lower pensions for new state workers, known as a “second tier” in pension jargon.

His budget said it was possible for state workers to retire at age 62 and receive more than 100 percent of their final salary from CalPERS and Social Security. He argued that 70 percent of pay is believed to be adequate to maintain the same standard of living in retirement.

“As governor in 1982, I signed into law SB 1326 that called for a Two-Tiered Retirement System to reduce overall pension costs,” Brown said on his 2010 campaign website. “Pension spiking was not permitted.”

Brown expected a lower pension to be negotiated with unions and developed by CalPERS and what is now Human Resources, said an aide, but it never happened.

[divider] [/divider]

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.