Originally posted at Next City.

By Rachel Dovey.

Innovation drives Santa Clara County’s economy, but like even the most Luddite areas of the U.S., residents of the California tech hub still rely on decades-old infrastructure to get around.

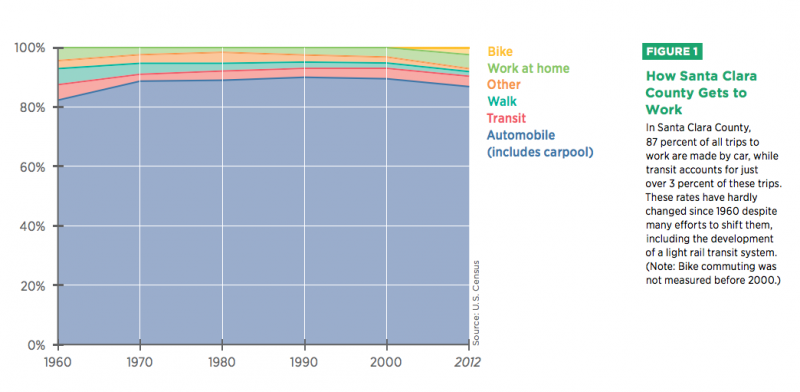

The region’s “cycle of auto-orientation” is the subject of a recent report by Bay Area non-profit SPUR. With available housing and Silicon Valley jobs, the South Bay’s population is expected to grow nearly 40 percent in the next 25 years. But the county, which houses San Jose, Cupertino and Mountain View, is overwhelmingly car-dependent, with around 87 percent of commuters driving to work every day — even though alternatives like bus and light rail exist. Built around orchards and subdivisions, the region’s car dependence comes from history and geography; planners serious about alternative transit need to move beyond “build it and they will come” and get creative.

The infrastructure around the region’s light rail is an example of mixed goals, catering to the car while also trying to substitute it.

“When the light rail system was designed, cities agreed that growth would be focused around transit stations,” the report states. “A total of $13 billion of private investment has occurred within one-half miles of the light rail system since it opened.”

But because so many people still drove in from flung-out neighborhoods, those developments were mostly car-centric office parks with suburban designs. As with other regions where rail is a first step toward urbanization, sidewalks and other pedestrian infrastructure weren’t prioritized. Meanwhile, several freeway projects were approved at the same time, helping to undermine the train.

(Source: SPUR)

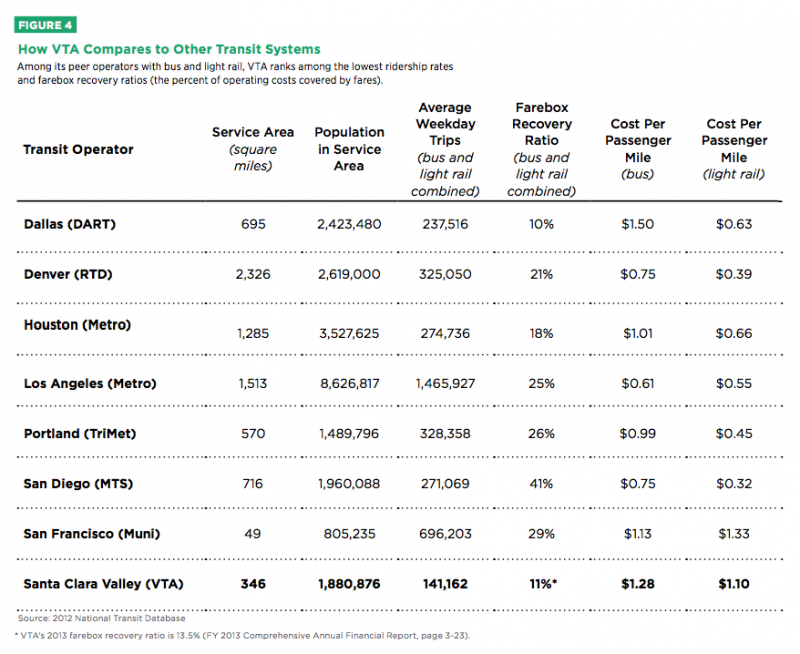

Bus service also suffers from the South Bay’s sprawled-out terrain and, counterintuitively, funding too many routes may actually be hurting ridership.

“There’s often this tension between coverage and efficiency because the area is so sprawled,” says Leah Toeniskoetter, the director of SPUR’s San Jose office. With limited funds, trying to send buses everywhere is probably not the best strategy to increase ridership overall. Rather, she suggests pooling resources on the lines where ridership is already strong and making them better.

(Source: SPUR)

“There need to be enough people that it actually makes sense on the fiscal side to run the service,” she says.

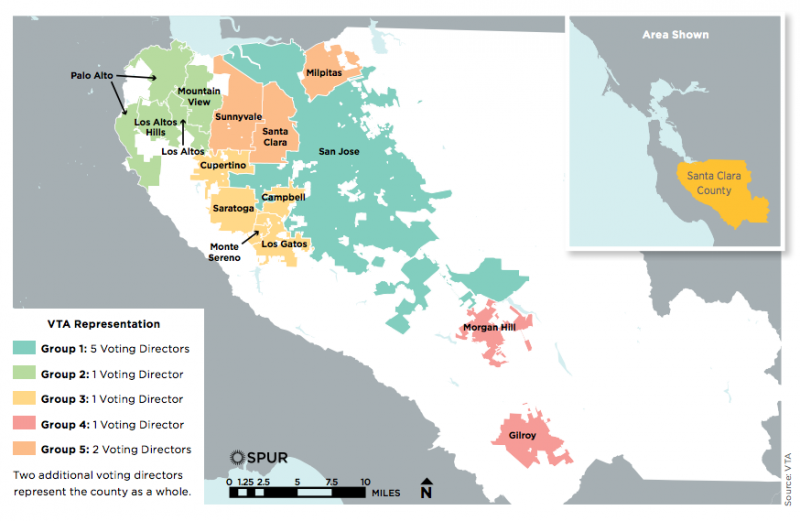

Meanwhile, because the county’s Valley Transportation Authority manages both roads and public transportation, dueling interests that reflect national politics often conflict — within one organization. And its elected board comes from across the county’s municipal spectrum, from San Jose to Sunnyvale, a structure that “leads to mixed goals and a lack of direct accountability for transit” according to SPUR.

(Source: SPUR)

“Although leaders and voters have supported transit, our research indicates that many of them view transit as a transportation mode for a narrow segment of the population,” the report states. “Transit lacks powerful political champions, and in the South Bay it has been typically presented as a social service rather than a mainstream transportation mode.”

Still, because it oversees multiple modes of transportation, VTA is uniquely positioned to guide future growth. And the agency is trying to look beyond simple building projects for decentralized ways to encourage alternative transit.

VTA is studying ride-shares and other on-demand services to supplement buses and shuttles, writes the agency’s deputy director of transportation planning Chris Augenstein in an email. It’s also preparing countywide bicycle plans and partnering with health organizations to highlight public transit as a means of getting fit. Shuttle service to the new Levi’s Stadium and discounted “eco-passes” for employers and universities are other incentives.

Still, the all-powerful market has driven housing and job location more than planning goals in past years.

“It’s often the case that VTA has urban design guidelines for orienting the front door of a building to a transit line, but they’re just guidelines,” says Toeniskoetter. “And this is a very suburban culture.”

Even the famous Apple campus in Cupertino is low-density and decentralized. It “faces inward,” Toeniskoetter says, and the campus’ introspection will become even more literal when it’s rebuilt as agiant circle.

And because the region seeks to attract jobs and grow economically, any urban design guidelines that could possibly scare businesses away are, she says, sometimes “viewed as against economic development.”

But as the county grows, high-quality, walkable public transportation can begin to reshape the sprawl into denser pockets and corridors.

“Transportation is only a means to an end, not an end itself,” the report states. “As part of the larger picture, transportation should help shape great places and support a high-quality of life — not contribute to degrading these things.”

But in a place that relies so heavily on cars despite its next-century economy, the suburban myth that business will suffer from urbanized transportation is, Toeniskoetter says, “one of the hardest stories to overcome.”

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at NextCity.