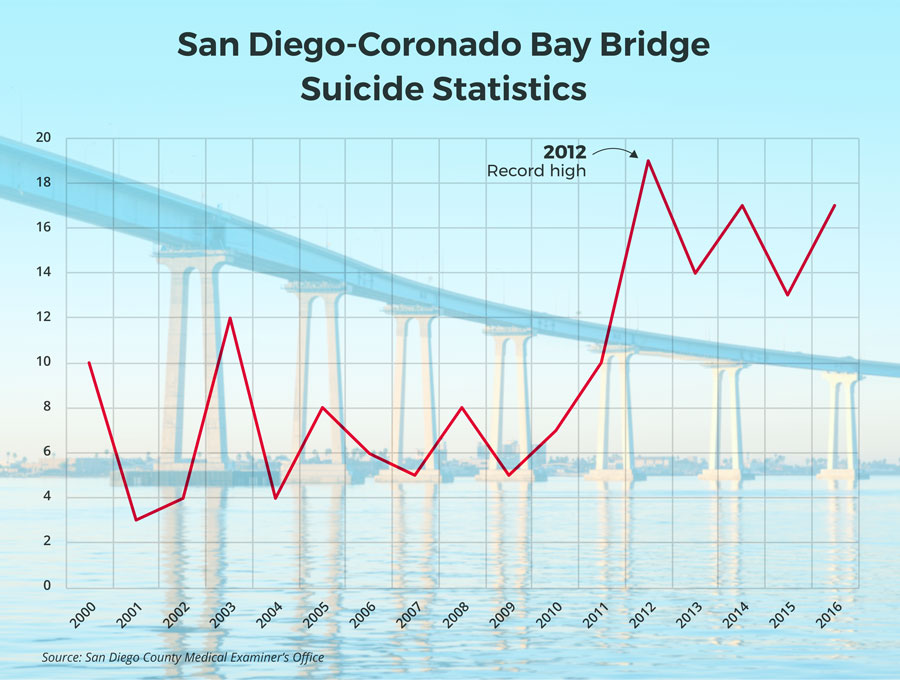

This week’s community meetings about a barrier to prevent suicides at the Coronado-San Diego Bay Bridge couldn’t be more timely: The last six years have seen an extraordinary and unexplained increase in jumps from the bridge.

The average annual number of suicides has more than doubled, and 2012’s death toll of 19 lives was the highest in the bridge’s nearly 50-year history. This year is on pace to reach or pass that number.

The bridge – with a death toll nearing 400 since 1969 – is poised to reach a morbid milestone. “If nothing is done soon,” Coronado Mayor Richard Bailey recently wrote, “the Coronado Bridge will experience more suicides and more closures from attempted suicides than any other bridge in our nation.”

He’s right. San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, now the deadliest bridge in the United States, is installing steel nets designed to prevent suicides there. Many other bridges worldwide with major suicide problems have installed barriers to prevent deaths, and research suggests they work. But until now, local and state officials have barely discussed the idea of a Coronado Bridge barrier.

Picture-Perfect Bridge Soon Drew the Hopeless

The $50 million Coronado Bridge opened in 1969 and quickly became a postcard-perfect icon of sun and sea in San Diego. “The “span of blue steel … arches across the bay and clasps Coronado in the grip of modernity,” raved The New York Times.

It took just three years before someone toppled over the bridge’s 34-inch railing to her death. The victim didn’t want to kill herself, however. Her husband forced her over the edge and was convicted of voluntary manslaughter.

Then people began to jump to their deaths on purpose. The total is likely more than 350, according to statistics provided by the Port of San Diego and the county medical examiner’s office. An exact number isn’t certain because of discrepancies between the numbers provided by the agencies.

The Port’s police officers recover the bodies of victims from San Diego Bay. Suicides typically require the services of two boat crew officers for three to four hours, according to the Port.

Only a few people have managed to survive the 200-foot fall to the water below, avoiding the usual causes of death for the jumpers – torn organs, internal bleeding, drowning.

“There’s nothing at all glamorous about jumping off a bridge,” Dr. Jim Dunford, medical director of the city of San Diego, told VOSD in 2008. “It’s not a swan song, diving into heaven. You really get a disfiguring, traumatic and dramatic death.”

In 2012, a Sudden Uptick in Bridge’s Death Toll

From 1973 onward, the annual suicide toll most years was in the single digits.

But something happened in 2011, as if a switch was suddenly turned on. Dramatically more people began driving to the bridge and killing themselves. (The bridge does not allow pedestrians, so those who kill themselves typically abandon their cars and leap from the edge.)

The number of bridge suicides in 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 were 10, 19, 14, 17, 13 and 17, respectively.

This year, as of Aug. 7, 11 people have jumped from the bridge to their deaths, according to the county medical examiner’s office. Officials provided information about nine of the victims — they were five women and four men, ranging in age from 20 to 60. Four were 47 or older.

If suicides continue at the same pace, 2017’s death toll is likely to reach or top 19 deaths, the previous record.

No Easy Explanation for Rise in Deaths

It’s difficult to determine how unusual the rise in bridge suicides is because the numbers are so small compared with the hundreds of annual suicides in San Diego County and the 40,000 or more in the U.S. each year. Still, the sudden growth in bridge suicides stands alone.

From 2011 to 2016, the bridge averaged 15 suicides a year. That’s more than double the average in the period from 2005 to 2010, including the height of the Great Recession, when the bridge’s average annual suicide toll was 6.5 lives. The nation and county have seen rising suicide rates in recent years but the increases have been small.

People who jump to their deaths from the bridge aren’t different, on the whole, than suicide victims in the county, said Joshua R. Smith, a senior epidemiologist with the county’s Health & Human Services Agency. Their genders, races and marital statuses are about the same.

In recent years, however, those who killed themselves at the bridge have been younger, on average, than in the county: Their average age is 38, compared with 50 countywide, Smith said.

Smith also noted a disturbing statistic that suggests proximity to the bridge plays a role: Coronado residents are seven times more likely to jump off the bridge to their deaths than those in the rest of the county.

Evidence Backs Barriers as Prevention Tools

Studies suggest that barriers prevent suicides at bridges and deter many people from jumping to their deaths.

In a 2013 analysis, researchers examined eight studies from around the world that explored what happened after officials installed nets or metal barriers at suicide magnet bridges. A ninth study in the analysis looked at what happened when a bridge was temporarily closed.

The researchers found that suicides at the bridges fell by between 79 percent and 91 percent. Suicides by jumping increased at nearby sites, however, but overall the number of these kinds of deaths went down.

In recent years, barriers have been installed on bridges in numerous cities across the world from Santa Barbara, Seattle and Toronto to Switzerland and Australia.

In San Diego, officials in the 1950s dramatically reduced the suicide death toll from Balboa Park’s Cabrillo Bridge by installing fencing that’s still present today.

And suicides from UC San Diego’s 11-story Tioga Hall dormitory building ended after a barrier was installed at the insistence of a victim’s mother.

Most recently, officials have begun constructing suicide barriers at Pasadena’s historic Colorado Street bridge over the Arroyo Seco and the Golden Gate Bridge, where suicides began 80 years ago this week, just weeks after its opening. Over eight decades, the bridge’s death toll has topped 1,600.

Construction on the $211 million Golden Gate Bridge barrier — a steel mesh net that will catch jumpers — is expected to be finished by 2021. The money will come from CalTrans, local transportation funds, a state mental health fund and other sources, including donations.

The 20-foot fall from the bridge to the net is expected to injure jumpers so badly that they won’t be able to climb out of it, said Lisa Locati, the bridge captain, in an interview. Officials are still figuring out how they’ll rescue people from the net, she said.

For CalTrans, Plenty of Reluctance on Barrier

The CalTrans officials who manage the Coronado Bridge have long resisted the idea of building a barrier.

“I don’t think there really is going to be … pressure until a public figure or a person related to the county Board of Supervisors goes off the bridge,” Drew Leavens, the chief of suicide prevention for the county at the time, told The Evening Tribune in 1985 when CalTrans failed to act after hearing from a coalition of activists and government officials sought a barrier.

Now, amid extensive fundraising and planning for a bridge lighting project expected to cost as much as $10 million, the first major effort to build a barrier in more than 30 years is afoot. CalTrans is studying the issue, and is holding community meetings in Barrio Logan and Coronado Wednesday and Thursday, respectively.

Meanwhile, San Diego state Sen. Ben Hueso has written a bill making its way through the legislative process that orders state transportation officials to study bridge safety, make recommendations and report back by next year.

Hueso did not seek the legislation in response to the bridge’s suicide toll. He acted after a suspected drunk driver flew off the bridge in 2016 and landed on a gathering of people in Chicano Park, killing four.

The bill initially allocated 1 percent of state transportation funding for bridge safety and gave priority to bridges that travel over parks like the Coronado Bridge. Those provisions have been removed from the bill.

There’s no sign yet of how much the Coronado bridge barrier will cost or where the money will come from. It seems clear, however, that the number of deaths will move ever closer to 400 as the Coronado Bridge nears its 50th birthday.

[divider] [/divider]