More stories are at http://calpensions.com

A 17-page CalPERS sales brochure told legislators a decade ago that a major increase in state worker pension benefits would not increase state costs, but annual state payments to the pension fund have soared from $159 million to $3.9 billion since then.

The professionally designed pamphlet apparently helped build a persuasive case in 1999 for SB 400, which sailed through the Senate on a 39-to-0 vote and passed the Assembly 70-to-7.

But now Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger wants to roll back pensions for new state hires to pre-SB 400 levels. The governor with only a half year left in office has said he won’t sign a new state budget without pension reform.

“The single biggest threat to the fiscal health and to California’s future obviously is our public pension system and the crisis that we have,” Schwarzenegger said in April as he endorsed a Republican-backed reform bill rejected by the Democratic majority.

The e-mail version of a news release for the governor’s round table pension discussion last week has an Internet link to the CalPERS brochure. The governor’s pension advisor, David Crane, quoted from the brochure at a legislative hearing in May.

The brochure contains several unequivocal statements that replacing a pension cut enacted in 1991 with major pension increases (some up to 50 percent), while also boosting payments to current retirees, would not increase state costs.

“NO INCREASE OVER CURRENT EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS IS NEEDED FOR THESE BENEFIT IMPROVEMENTS,” says a line written in capital letters describing the impact on taxpayers.

“This is a special opportunity to restore equity among CalPERS members without it costing a dime of additional taxpayer money,” says a quote attributed to “Dr. William D. Crist, President, CalPERS board, June 16, 1999.”

Crane told the hearing the brochure failed to say the state would have to pay for investment shortfalls, the stock market would have to boom, CalPERS employees would get bigger pensions, and CalPERS board members get campaign money from beneficiaries.

“It’s nothing short of astonishing that the CalPERS proposal, which promoted the largest non-voter approved debt issuance in the state’s history, was not accompanied by disclosures of risks or conflicts of interest,” Crane said.

The brochure reflects the confidence of strong investment earnings, from 15.3 percent to 20.9 percent in the four previous years. The half dozen separate funds covered by the bill were bulging, with funding levels from 100 percent to 139.7 percent.

“CalPERS has enjoyed excess earnings in its fund, as a result of the booming stock market and investment strategies of the CalPERS board,” said the brochure.

Now that the funds were flush the brochure, titled “Addressing Benefit Equity: the CalPERS proposal,” said pensions can be boosted to solve a number of problems.

-Some retirees had lost up to 25 percent of the original purchasing power of their pensions. Retirees in the California Public Employees Retirement System get a 2 percent annual cost-of-living adjustment, which can fail to keep pace with inflation.

-The average CalPERS retiree was receiving $1,175 a month, when the 1999 poverty level for a family of two was $922 a month. Non-teaching school retirees were receiving an average of $922 a month.

-A pension cut enacted for employees hired after July 1, 1991, had some working side-by-side in the same job with workers hired earlier who would receive a much higher pension.

-Two-thirds of local government agencies in CalPERS (the brochure lists nearly 400) gave non-safety employees a higher pension than received by similar state workers. State pensions for safety workers, such as the Highway Patrol, also lagged.

“To attract and retain high caliber state safety employees, it is necessary to raise the level of benefits to remain competitive,” said the brochure.

What the brochure did not say was that the political timing for a pension increase was right. The Republican governor who pushed through the pension cut, Pete Wilson, had been replaced in 1999 by the first Democratic governor in 16 years, Gray Davis.

Another inequity mentioned in the brochure: The annual worker contribution, 5 percent of pay for miscellaneous workers, was fixed by statute and did not change as the annual state pension payment, then 12.7 percent of pay, dropped sharply.

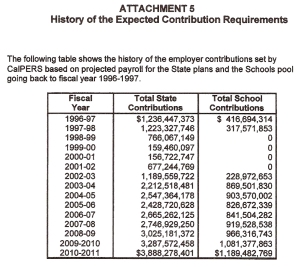

The CalPERS board used the surplus to cut the annual state payment, $1.2 billion in fiscal 1997-98, to about $766 million in fiscal 1998-99. The brochure said the payment would drop to $160 million in fiscal 1999-00 if the legislation was enacted.

The brochure also made a specific prediction: “CalPERS fully expects the state’s contribution to remain below the 1998-99 fiscal year for at least the next decade.” In other words, below $766 million.

The first year cost of the benefit increase, about $600 million, would begin in fiscal 2001-02, said the brochure. That increase, coming on top of $160 million in the previous year, would be a total of about $760 million.

Chart from CalPERS board May agenda

So, why didn’t the state payment stay below $766 million for the next decade? The CalPERS explanation is not that investment earnings fell short, but that the state payroll grew much faster than expected.

A website, Calpersresponds.com, attributes 51 percent of the increase to payroll growth during the last decade, 27 percent to the SB 400 benefit increase, 8 percent to other benefit changes, and miscellaneous factors 14 percent.

The CalPERS brochure said the SB 400 benefit increases would be funded with “excess assets” and two maneuvers: inflating the value of assets from 90 to 95 percent of market value and “amortizing” excess assets over 20 years instead of 30 years.

At the round table discussion last week, Schwarzenegger apparently figured that all of the state payments to CalPERS during the last decade are attributable to SB 400, except for continuing the $160 million annual tab when the legislation was enacted.

“I also want to just mention that if we would have not done SB 400 10 years ago we would now have $20 billion set aside, because it cost the taxpayers in California $20 billion in the last 10 years,” he said.

The governor said if the $20 billion spent on CalPERS had been placed in a rainy day fund, the state could have spread the money over the last four deficit-ridden years, avoiding cuts in important programs.

If state worker pensions trailed local government pensions before SB 400, the measure made the state a leader with what became a trendsetting increase for the Highway Patrol.

The patrol went from 2 percent of final pay for each year served at age 50 to 3 percent at 50. CalPERS also passed a resolution in 2001 offering to inflate the assets of local governments to help them pay for pension increases authorized by AB 616.

Now the Schwarzenegger administration has negotiated a tentative agreement that would lower benefits for new patrol hires to 3 percent at age 55, part of cost-cutting agreements pending with half dozen unions that could save $138 million this year.

“If similar agreements are reached with the state’s six other employee unions, state savings in FY 2010-11 would total $2.2 billion, with $1.2 billion of that from the general fund,” a governor’s news release said last month.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at http://calpensions.com