A new study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office provides additional insight into the challenges facing not only California’s pension system, but also public pensions across the country.

It comes as no surprise that the relative health and funding ratios have suffered greatly as a result of the Great Recession. However, the GAO’s report also compares a variety of funding and benefit solutions that are being tried, implemented, and tested across the nation. From adjusting benefits and increasing employee contributions to two-tiered approaches and hybrid systems; 40 states and numerous local entities have made substantive alterations to their pension programs.

As the study discusses, they all were designed to serve a purpose but some may be more detrimental than helpful.

The March report offers in its introduction the following summary of actions taken in recent years:

“Since 2008, the combination of fiscal pressures and increasing contribution requirements has spurred many states and localities to take action to strengthen the financial condition of their plans for the long term, often packaging multiple changes together…

“At the same time, some states and localities have also adjusted their funding practices to help manage pension contribution requirements in the short term by changing actuarial methods, deferring contributions, or issuing bonds, actions that may increase future pension costs.”

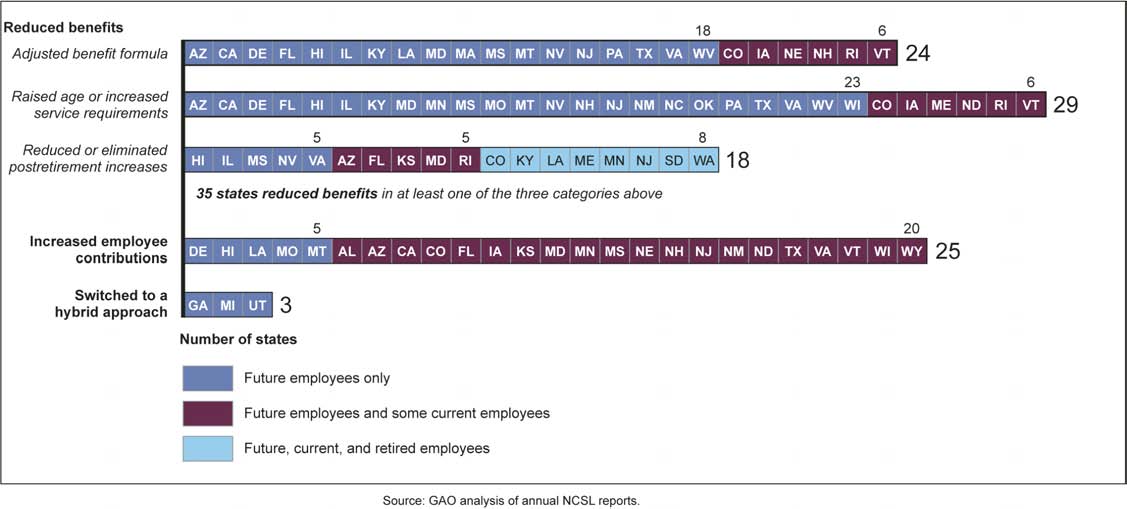

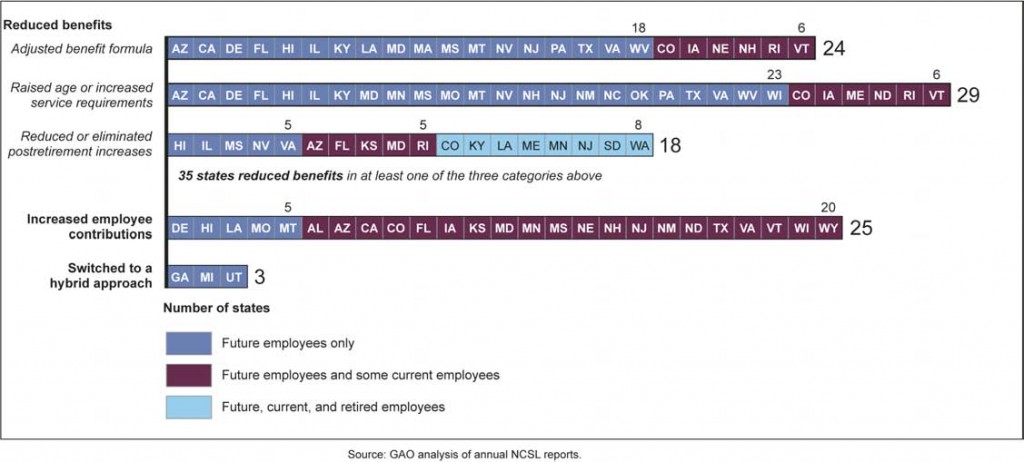

In total, 35 states reduced pension benefits for future employees and one cancelled Cost of Living Adjustments for current retirees. Half of all states increased employee contributions. Three states switched to hybrid pension systems.

Nationally, 27 million people are covered by state and local pension plans, 78 percent of who participate in a defined benefit plan. About one-fourth of participants are not eligible for Social Security.

Nationally, 27 million people are covered by state and local pension plans, 78 percent of who participate in a defined benefit plan. About one-fourth of participants are not eligible for Social Security.

“Most plans have experienced a growing gap…” reads the report, “meaning that higher contributions from government sponsors are needed to maintain funds on an actuarially based path toward sustainability.”

However, immediate insolvency is not a risk for most plans, which have sufficient assets to cover benefit commitments for a decade or more.

However, adjusting for long-term stability can be challenging when it often requires increased contributions by employers and employees. Understandably, employees are often reluctant to increase contributions at the detriment of their take-home wages, and employers are facing increasing demands on decreasing resources.

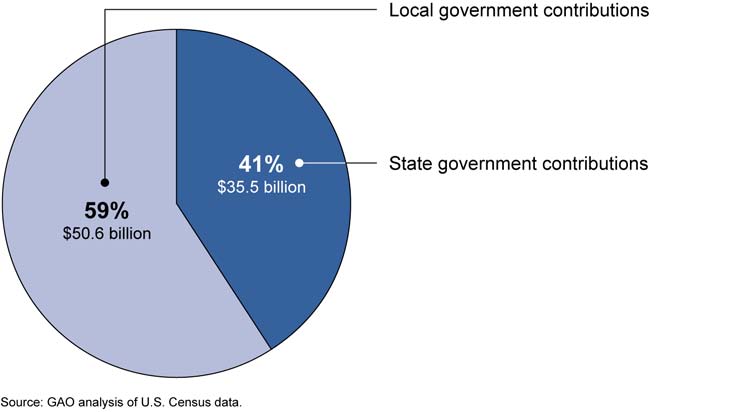

According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, states had to close a combined budget gap of $230 billion between 2009 and 2011. The National League of Cities estimates that local government budget solutions ranged between $56 and $83 billion from 2010 and 2012. Local governments contribute more to pensions than their state counter parts.

In Denver, Colorado, the city reduced pension benefits for future employees by reversing previous benefit enhancements, extending the number of salary years used to calculate benefits, and raising the retirement age. These reforms are expected to reduce the city’s pension contributions by 1.65 percent of payroll over the next 30 years.

More drastic approaches to reforming the defined benefit structure occured elsewhere. Michigan, Utah, and Georgia have adopted hybrid systems for large segments of their public employees. Those efforts, the GAO found, have had mixed results.

“Switching to a defined contribution plan can involve additional short-term costs for plan sponsors, since contributions from new employees go toward their own private accounts rather than paying off existing unfunded liabilities of the defined benefit plan once it is closed to new employees,” wrote the study’s authors.

Additionally, the Georgia plan demonstrates some of the challenges and benefits of hybrid plans. On one hand, the state contributes only 6.54 percent of payroll for employees in the hybrid system, down from 10.41 percent under the old system. However, 80 percent of employees were contributing the bare minimum 1 percent towards their 401(k) plan. That would likely leave them unprepared to finance retirement.

The state has had little success thus far in encouraging employees to boost

participation.

Others have taken action to address pension funding that could have a detrimental impact in the long run.

Pennsylvania faced a 19 percent increase in its employer contribution. Instead, the state enacted annual caps in how much its employer contribution could increase each year: 23 percent in 2012, 3.5 percent in 2013, and 4.5 percent there after.

“Although adjusting plan funding produced some short-term savings for state and local budgets, it also increased the unfunded liabilities of the pension system and will necessitate larger contributions in the future.”

The GAO estimates that the caps will save $2.5 billion over the next four ears, but will add $7 billion to the funding gap over the next 32 years. That’s why the state has called for benefit reductions equal to $8.5 billion, for a net savings of $1.5 billion.

Local governments also took similar approaches. Philadelphia deferred $240 million in contributions over two years. However, under state law, those deferrals must be paid back, with interest, by fiscal year 2014. The city adopted a 1 percent increase in sales taxes to cover the costs.

Another approach used nationally as well as in California is the issuance of Pension Obligation Bonds. In Illinois, the state issued $7 billion in POBs between 2010 and 2011. Those bonds have a nine-year debt service of $1 billion annually.

Lastly, many pension systems have adjusted how their actuaries calculate funding. “Smoothing” is designed to temper losses on investments by spreading the loss over a number of years. It is a practice that many have criticized CalPERS for in recent years, and a practice that could be forbidden under proposed changes by the General Accounting Standards Board.

In Illinois, the state went from reporting market value – which did not include any smoothing – to a five-year smoothing method. As a result, the state’s contribution dropped by $100 million.

“Plan actuaries noted that this strategy only defers contributions when plan assets experience a loss, as they did in fiscal year 2009. Future contributions will be higher than they would have been previously once the fiscal year 2009 market losses are fully recognized.”

It is important to note that these trends were not only predictable, but they were inevitable. Although it was common for income to outpace expenses before 1990, that trend reversed in the early 1990s. That’s when the gap and ratio between active members and retirees began shrinking.

“As such, payments to retirees increased relative to plan contributions and, as a result, in more recent years, sector-wide expenditures have outpaced contributions.”