Data-analysis techniques first developed by retailers to predict their customers’ behavior are being adopted by police forces across the country, and they’re seeing encouraging results. [Editor’s note: Santa Cruz, CA is highlighted as a case study below].

Originally posted at GOVERNING.

By John M. Kamensky.

The use of data to investigate and solve crime certainly isn’t new: Crime mapping has been used by detectives since it was developed by an Italian geographer and a French mathematician in 1829. Today, however, new data, statistical tools and other advanced technologies are helping police departments across the country turn traditional police officers into “data detectives” who not only solve crime but predict it.

“Predictive policing” is an adaptation of business techniques initially developed by retailers such as Netflix and Walmart to predict the behavior of consumers. In a new research report for the IBM Center for the Business of Government, Dr. Jennifer Bachner of Johns Hopkins University tells compelling stories of the experiences that several cities are having in using these cutting-edge crime-busting methodologies.

The Santa Cruz, Calif., police department was one of the first in the United States to embed predictive policing into its regular day-to-day operations. During the pilot phase, which began in mid-2011, burglaries dropped by 27 percent when compared to the previous year. Since then, the department has increased arrests by 56 percent and recovered 22 percent more stolen cars.

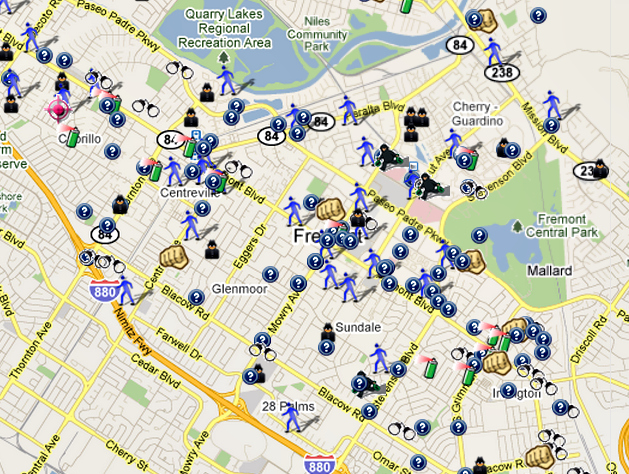

What did the Santa Cruz police do? The core of the program, writes Bachner, is “the continuous identification of areas that are expected to experience increased levels of crime in a specified time-frame.” The system divides a map of the city into 150-by-150-meter cells. Drawing upon a database of past criminal incidents, a computer algorithm assigns probabilities of crime occurring to each cell, giving greater weight to more recent crimes.

Prior to their shifts, officers are briefed on the locations of the 15 cells with the highest probabilities and encouraged to devote extra time to monitoring these areas. “It’s almost like Neighborhood Watch in the next century,” Deputy Police Chief Steve Clark wrote in a local newspaper.

Bachner lists three categories of analytic techniques that Santa Cruz and other police departments are using to predict and prevent various kinds of crime:

Analysis of space. There are about a half-dozen “hot spot” detection methods. “Point location,” for example, involves mapping specific addresses where crimes have been reported and looking for patterns, since crime is more likely to happen near locations that have experienced it in the past. In “hierarchical cluster” analysis, crime incidents are grouped to prioritize patterns. And in “density mapping,” the resulting map looks similar to a topographical map.

Analysis of both space and time. A second, and related, set of techniques goes a step further. For example, a software program called CrimeStat III, developed by the National Institute of Justice, permits examination of the path a criminal has taken. WithSeries Finder, being developed at MIT, “an analyst can perform a correlated walk analysis … which examines the temporal and spatial relationships between incidents in a given sequence to predict the next incident,” writes Bachner. But while this approach works in theory, she says, it “requires refinement before it can be regularly used by police departments.”

Analysis of social networks. This approach, aimed at determining persons of interest rather than locationsof interest, is new but growing in importance in the new age of social media. Like all human institutions, organized crime and gangs depend on interpersonal relationships. There are a number of different statistical and visualization tools that have been developed to analyze social networks, and Bachner reports that the Richmond, Va., police department, working with Virginia Commonwealth University, has developed a successful pilot program to integrate social network analysis into crime-fighting.

Bachner doesn’t suggest that predictive analytics — in policing or in other policy areas — is some kind of silver bullet. It is an additional tool that supplements existing methods. Community policing, for example, remains an important strategy for deterring crime. “Nevertheless,” she notes, “policing, like many other fields, is undoubtedly moving in a data-driven direction.”

Of course, having the technology doesn’t mean it will get used. Analytic techniques such as hierarchical and partitioned clusters can be intimidating to non-analysts. Bachner found that getting buy-in from the on-the-street police officer was crucial and that “it cannot be imposed on unwilling officers as a replacement for experience and intuition.” But once officers begin using the tools of predictive policing to supplement their traditional approaches, she writes, they like the results.