Private equity firms have produced big profits for CalPERS, not to mention a pay-to-play scandal, while keeping a big share for themselves as an incentive — traditionally 20 percent of profits plus annual management fees of up to 2 percent.

With its size as the nation’s largest public pension fund providing leverage in negotiations, and a new emphasis in recent years on cutting management fees, CalPERS seems likely to have negotiated favorable deals with private equity firms.

But after the board was told last April that CalPERS could not track the incentive payments, known as “carried interest,” a wave of media criticism grew with stories in the New York Times late last month and Fortune magazine last week.

A pension fraud investigator, Edward Seidle of Benchmark Financial Services, launched an Internet fund-raising campaign on Kickstarterto raise $750,000 for a “forensic investigation” of the California Public Employees Retirement System.

Last week, CalPERS announced that a new reporting system under development since 2012 will enable the reporting of “the total carried interest” paid to its private equity firms during fiscal 2014-15, probably this fall.

The report may be incomplete. CalPERS sent a new e-mail request last week to the 6 percent of its private equity firms that have declined so far to provide the information on carried interest.

The CalPERS board member who raised the tracking issue, J.J. Jelincic, estimated last April that the carried interest could be $600 million to $900 million a year, adding to the $1.6 million in total external management fees reported last fiscal year.

Jelincic said last week that, contrary to his earlier skepticism, staff has convinced him they indeed do not know the carried interest amounts. At a past conference, he said, a staff member estimated that the average carried interest is roughly 10 percent of profit.

Private equity firms with a strong record of returns desired by investors apparently can charge 20 percent or more, Jelincic said. In a kind of market pricing, other less proven private equity firms may agree to a much lower carried interest rate.

Part of the media criticism is that in 2011 CalPERS dropped a consultant, LP Capital Advisors, that had been monitoring its private equity portfolio, which has about 350 managers with 700 funds and a net value last year of $31 billion.

Brad Pacheco, a CalPERS spokesman, said the consultant’s reports were incomplete, inconsistent and covered the total private equity fund, not the CalPERS share of carried interest.

The report this fall from the new CalPERS system, called the Private Equity Accounting and Reporting Solution or PEARS, will use the industry standards issued in 2012 by the International Limited Partners Association.

A chart in an “investment office cost effectiveness” report to the board last April shows the private equity base management fees, excluding the profit share, dropping from about 2 percent of assets in 2010 to 1.5 percent in 2014.

Several large private equity firms agreed to lower their CalPERS management fees after a pay-to-plan scandal surfaced in 2009, prompting a number of reforms by CalPERS and the Legislature.

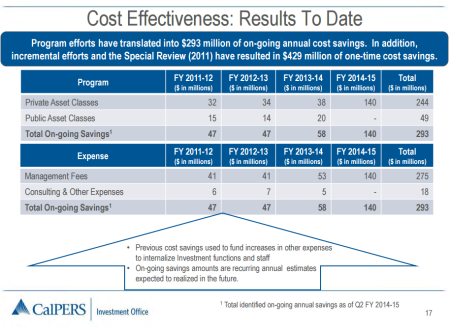

The April report showed an investment management cost for all CalPERS funds of 0.41 percent, below the 0.48 percent benchmark for similar pension funds. In the last four years one-time savings were $429 million and ongoing savings grew to $293 million a year.

“The kinds of savings that are indicated here — you need to be applauded for the work in that area,” Henry Jones, the investment committee chairman told the staff after hearing the report. “I think we need to let the public and world know about these savings as we go forward.”

Private equity investments, mainly available only to pension funds and other large institutional investors, are expected to yield higher returns than stocks traded on the public market.

One example of their importance: After huge investment losses in the 2008 stock market crash and economic recession, both CalPERS and the California State Teachers Retirement System increased their private equity allocations.

The CalPERS target for private equity jumped from 10 to 14 percent of the investment portfolio, CalSTRS from 9 to 12 percent. The CalPERS target has since returned to 10 percent of a portfolio valued last week at $308.7 billion.

By far the most lucrative and controversial type of private equity is the “leveraged buyout,” now about 60 percent of CalPERS private equity assets. Often a company is purchased with loans that use the targeted company’s own assets as collateral.

Advocates say the companies purchased in leveraged buyouts typically are modernized by outside experts, made more cost-efficient and competitive in various ways and returned to the market after several years in a kind of “creative destruction” that is good for the overall economy.

Critics say too often companies are “ripped, stripped and flipped,” jobs outsourced, borrowing increased simply to pay the purchaser dividends, bankruptcies declared, and a new class of billionaires created as public pensions help gut the economy.

In what some call private equity’s “golden years” before the market crash in 2008, a former CalPERS board member, Alfred Villalobos, collected more than $50 million in “placement agent” fees from firms seeking CalPERS investments.

A former board member who became the CalPERS chief executive, Fred Buenrostro, pleaded guilty to bribery-related charges for aiding Villalobos and awaits sentencing. Villalobos died last January while awaiting trial, an apparent suicide.

Last week Jelincic said tracking private equity profit shares should help CalPERS monitor how investments are used. He also suggested that CalPERS consider doing its own private equity investments, even if the needed “skill sets” require higher pay.

“We ought to take a serious look at whether we need to bring it in-house,” said Jelincic. “But if you don’t know what you are paying, you don’t know which way to go.”

A long-time CalPERS investment office employee, Jelincic has been on leave since his election to the board in 2010. During his campaign, the former president of the largest state worker union advocated more internal investment management.

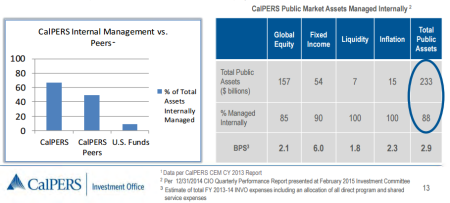

The cost report last April said managing a larger percentage of its investments internally, particularly compared to other U.S. public pension funds, is one of the reasons CalPERS costs are lower than the international benchmark for its peers. (See chart below)

As if to show how both CalPERS and the times have changed, pressing firms to reveal their profit share and suggesting a switch to internal management is a stark reversal of the old attitude toward private equity.

In 2006 Los Angeles Times reporters made a Public Records Act request to CalPERS for letters, e-mails and memos from Villalobos and former state Sen. Richard Polanco about investment opportunities.

Rejecting the request, a letter from a CalPERS attorney to the Times said “the release of the (sic) some of the requested information may harm CalPERS’ ability to continue to invest with top-tier equity funds.”

Some private equity firms warned that “CalPERS’ current status as an ‘investor of choice’ will be damaged,” said the letter, and others “recently expressly refused to allow CalPERS to invest with them” due to concerns about disclosure.

[divider] [/divider]