When Sonoma County employees negotiated a retroactive first-class pension formula in 2002, they agreed to pay for the increased cost by contributing an additional 3 percent of their pay to the pension fund over 20 years.

Then a number of employees, more than anticipated by the county, retired and collected the larger pension without paying for it, a Sonoma County Civil Grand Jury report said earlier this year.

A retroactive pension increase at no additional cost to employees is common among California public pension systems. The best-known example is the retroactive increase for active and retired state workers sponsored by CalPERS, SB 400 in 1999.

But the size of the Sonoma County pension increase, along with the failure to anticipate more workers taking advantage of it, is one of things that led to unusual pension activism in the county and a distrust of county officials.

“The key driver of the pension problem was the retroactive increases which lead higher pensions and accelerated retirements at younger ages,” says the website of New Sonoma, a reform group led by Ken Churchill.

Sonoma County’s pension cost increased from $21 million in 2000 to $105 million early last year. The pension debt or “unfunded liability” soared from $10.8 million to $449 million during the same period.

When a business-labor-environmental coalition urged voters to approve a ¼-cent sales tax increase last June to improve deteriorating county roads, opponents warned the money could go to pensions. Measure A was rejected by 63 percent of the voters.

“This shows that there was a real concern about the county’s unsustainable pension costs, and it sends the message that the board of supervisors needs to continue its forward march toward pension control,” Dan Drummond, Sonoma County Taxpayers Association executive director, told the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat after the vote.

Another grass-roots group, Save Our Sonoma Roads led by Craig Harrison, urged the Stockton bankruptcy judge last year to require the city to cut its pension debt, setting a precedent for reducing the pension costs of other local governments.

Harrison told the court that Sonoma County roads, winding 1,384 miles through famous wine country and a scenic coastal area, are in disrepair because surging pension costs are eating up maintenance funds. The judge rejected the Sonoma group’s filing.

Last week, a seven-member independent advisory citizen committee on pensions met for the first time. It was appointed by the Sonoma County board of supervisors and given a $150,000 budget.

The committee of outside experts has no stake in the pension system. In six to nine months, it’s expected to give the supervisors an evaluation of recent cost-cutting reforms and suggestions for more changes.

“If there is something that we can do today to save the system dollars and the taxpayers dollars, we definitely should implement that going forward,” Supervisor David Rabbitt said as the board approved formation of the committee last April 21.

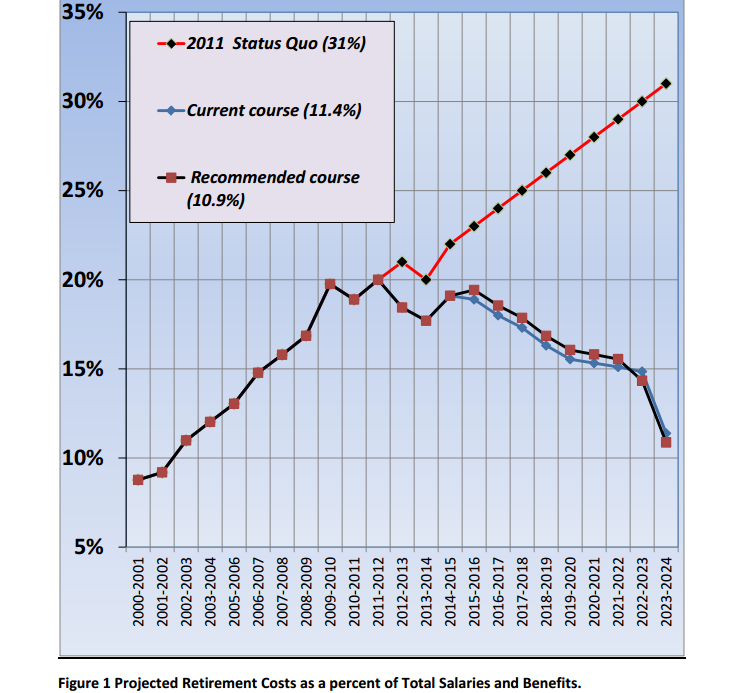

A series of county and state cost-cutting reforms is expected to drop county pension costs to about 11.4 percent of pay in eight years, a sharp cut from 31 percent of pay expected before the reform, said an updategiven to the board on Jan. 27.

A board “ad hoc” committee on pension reform in 2011 led by Supervisors Rabbit and Shirlee Zane set a target of reducing pension costs to 10 percent of pay during the next decade, while also proposing an independent citizens advisory committee.

In addition to containing costs, the other broad goals recommended by the ad hoc committee are “maintain market competitiveness and workforce stability” and “increase accountability and transparency.”

The January update estimated that $178 million had been saved through fiscal 2023-24 — lower pensions for new hires $92 million, curbing “spiking” $41.3 million, and $44.7 million from ending employer payment of the worker’s pension contribution.

In other steps, the board made an additional $3.5 million payment to reduce the pension debt, phased in a maximum $500 a month payment for retiree health care, and began a matching payment for contributions to individual retirement accounts.

The grand jury report said new hires receiving a lower pension formula (2 percent of final pay for each year served at age 62 and 2.5 percent at 67) agreed to contribute 3 percent of pay to help cover the cost of the retroactive increase in 2002.

The “legacy” employees hired before Gov. Brown’s pension reform imposed the lower formula for new hires on or after Jan. 1, 2013 (3 percent of final pay per year served at age 60) also are contributing 3 percent of pay for the retroactive increase.

One of the two grand jury recommendations, in addition to annual pension reform updates, is including the annual payment toward pension obligation bonds “in measurements of the county’s ability to meet its future pension obligations.”

The county recently paid off a $97 million pension bond issued in 1993. But the county issued a $231 million pension bond in 2003 and a $289 million pension bond in 2010.

“The combined outstanding balance of the county’s two remaining pension obligation bonds is $459.2 million,” said the grand jury report. “The county’s financial staff strongly asserts there is no intention to issue any additional pension bonds.”

The report also said pensions were 82 percent funded as of Dec. 31, 2013, retirees outnumber active employees (4,394 to 3,383), and low reserves have prevented pension cost-of-living adjustments since 2008 while inflation increased 13 percent.

At the April 21 board meeting, Ken Churchill of New Sonoma remained skeptical of the county staff projection that employer costs would be reduced to 10 percent of pay by fiscal 2023-24.

“It is based on the idea that we are not going to have a single dime’s worth of additional changes in actuarial assumptions and our investments are going to earn 7½ percent,” Churchill said. “Over the last 13 years they have been off by $62 million a year of their prediction of what pensions were going to cost us — $62 million a year.”

“So, it’s hard to believe that it’s going to be zero for the next 13 years,” he said. “I think if we hit a 5½ percent return, which is likely, we could see pensions costing an additional $65 million a year on overage for the next 13 years.”

Churchill was not among the seven selected to serve on the citizens committee by Rabbit and Susan Gorin, the board chairwoman. The members are Jack Atkin, Lawrence Heiges, Martin Jones, Rebecca Jones, Deborah Lauchner, Bob Likins, and Richard Tracy.

At the meeting last week, a retired actuary, Likins, was chosen to be temporary committee chairman. There were preliminary discussions of state open-meeting law and the committee’s scope of action. The next meeting was set for Oct. 23.

[divider] [/divider]