Social Security recipients get no raise this year because inflation last year was near zero. But more than half of CalPERS pensions will get a raise in May of 1.5 to 4 percent.

How does this happen, when both Social Security and the California Public Employees Retirement System have annual cost-of-living adjustments based on the rate of inflation?

“The law does not permit an increase in benefits when there is no increase in the cost of living,” Social Security recipients were told of the federal program‘s rules. “So your benefit will stay the same in 2016.”

That seems simple and straight forward. In contrast, the CalPERS method for a cost-of-living adjustment, even though its inflation index shows little or no inflation this year, seems almost comically convoluted.

A CalPERS report last week said its cost-of-living index (CPI-U for all urban consumers) increased only 0.12 percent last year, far below the one percent threshold needed to trigger a cost-of-living adjustment for the year.

CalPERS plans also have a cap on the amount of the annual cost-of-living adjustment, 2 percent for about 95 percent of retirees. When inflation is below the threshold or above the cap, the inflation not used for an adjustment can be “banked” and applied in future years.

The report gave an example of what happens when inflation is below the threshold: “In the future, when the inflation rate exceeds one percent, the 0.12 percent increase retirees did not receive in 2016 will be factored in to that year’s adjustment.”

When asked to clarify the cost-of-living adjustment policy at a board meeting last week, Anthony Suine of the CalPERS staff gave an example of what happens when inflation is above the cap.

“In the early 2000s when inflation was much higher than the 2 percent, for instance, that banked up,” Suine said. “So when it has been lower, the retirees who have been retired for longer were still seeing the benefits of that banked up cost-of-living adjustment.”

Now after several years of low inflation, he said, anyone that retired after 2005 does not have enough in the bank to reach the 1 percent threshold needed for a cost-of-living adjustment.

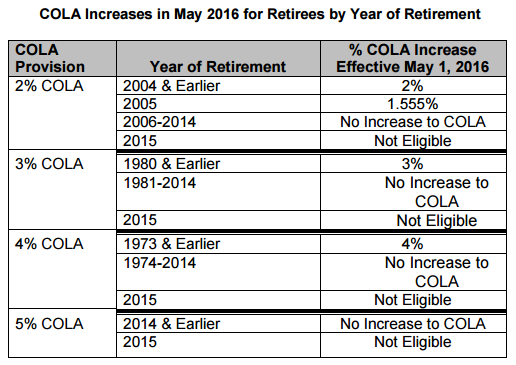

As a result, about 45 percent of CalPERS retirees will not receive a cost-of-living adjustment this year. But 55 percent of the retirees will begin to receive a cost-of-living adjustment in their monthly payment in May, most getting a 2 percent increase. (see chart)

State and school workers are among the 95 percent of retirees in plans with a 2 percent cap on the annual cost-of-living adjustment. The rest are local governments: 67 plans with a 3 percent cap, 12 plans with a 4 percent cap, and 38 with a 5 percent cap.

To get a cost-of-living adjustment in one year that is as high as the plan’s cap, inflation in the previous year would have to be as high as the cap.

“The cost-of-living adjustment is limited to the lesser of two compounded numbers — the rate of inflation or the cost-of-living adjustment contracted by the employer,” said the report.

Using a different method, the cost-of-living adjustments received this year by members of most large independent county retirement systems, which operate under a 1937 act, will include recent retirees.

The Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association approved a 2 percent cost-of-living adjustment beginning April 1, citing a 2.03 percent increase last year in the federal urban consumer index for the Los Angeles-Orange-Riverside County area.

The San Diego County Employees Retirement Association approved a 1.5 percent cost-of-living adjustment beginning March 31, citing a 1.62 percent increase in the consumer price index for the San Diego area.

The San Mateo County Employees Retirement Association approved a 2 percent or 2.5 percent cost-of-living adjustment (depending on the plan) beginning April 1, citing a 2.61 percent increase in the index for the San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose area.

The San Mateo system website has a reminder for members considering retirement this year: “If you want to take advantage of this year’s COLA rate, you must retire on or before April 1.”

The Sacramento County Employees Retirement System, in what some might consider a stretch, bases its cost-of-living adjust on the Sacramento-Oakland-San Jose consumer price index.

The Sacramento County system, citing the 2.61 percent increase in the Bay Area, approved cost-of-living adjustments (depending on the plan) of zero, 2 percent, 2.5 percent or 4 percent beginning April 1.

At the CalPERS Pension and Health Benefits Committee meeting last week, board member Henry Jones and the staff member, Suine, had a brief exchange about the inflation index.

“Some questions have been raised about why we don’t use some inflation factor from California as opposed to the U.S.,” Jones said. “Can you comment on that?”

Suine said the national CPI-U used by CalPERS is required by state law. He said the federal government uses a “clerical wage earner” index that produced a similar near zero result last year.

“We could consider other ones through legislation,” Suine said. “Not that I’m advocating,” Jones said. “I just wanted to get an explanation.”

If over time CalPERS pensions lag far behind inflation, a Purchasing Power Protection Allowance keeps them from falling below 75 percent of original purchasing power for state and school retirees and 80 percent for local government retirees.

The California State Teachers Retirement System has similar purchasing power protection for its pensions that get an annual cost-of-living adjustment of 2 percent, a fixed amount based on the original pension.

But the CalSTRS purchasing protection program, called the Supplemental Benefit Maintenance Account, keeps pensions from falling below 85 percent of original purchasing power and has an unusual and very costly funding source.

The state annually contributes 2.5 percent of the teacher payroll to the CalSTRS supplemental program, $607 million this fiscal year. Last year, the program had a giant reserve, $11.5 billion, and paid only $193 million to 52,474 retirees.

CalSTRS apparently has done no analysis to determine whether funding purchasing protection through the regular employer-employee contribution rate, like CalPERS, would be more cost-efficient than creating a giant reserve that has grown from $5.3 billion in 2008.

Meanwhile, finding a fair and rational method for cost-of-living adjustments is not a problem for most of the pensions remaining in the private sector, which has been switching to 401(k) individual investment plans.

A federal Bureau of Labor Statistics survey in 2000 found that only 9 percent of blue collar and service industry employees who are in traditional pension plans received an automatic cost-of-living adjustment.

[divider] [/divider]