For more than a year, SANDAG did not disclose an $8.4 billion cost increase facing the projects included in TransNet, its tax-funded transportation infrastructure program. Together with a forecasting error the agency also failed to disclose, the problems mean TransNet is $17.5 billion short.

By Andrew Keatts.For more than a year, SANDAG did not disclose an $8.4 billion cost increase facing the projects included in TransNet, its tax-funded transportation infrastructure program approved by voters in 2004.

In an official plan last year outlining the long-term status of TransNet, the agency relied on out-of-date cost estimates that made the program appear to be on sound financial footing.

It’s the latest in a series of moves SANDAG made that hid uncomfortable truths regarding TransNet and another proposed tax hike, Measure A. SANDAG also misled voters in November about how much money Measure A would generate, and recently admitted that an error in its forecasting model had dramatically overstated the revenue expectations for TransNet.

SANDAG finally disclosed the true costs facing TransNet in December 2016. That was 14 months after those cost estimates had been fully updated – by SANDAG itself – and just a month after voters rejected Measure A.

For a year, then, SANDAG’s failure to use the most up-to-date project costs let it obscure the shortfall facing TransNet.

“To follow good policy tenants of fiscal transparency, they should have incorporated the latest cost estimates into their evaluation of TransNet – for sure,” said Lucy Dadayan, a senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, a public policy research institute at the State University of New York. “Unfortunately, it sounds like this was more of a political gimmick in hopes of passing Measure A.”

The agency officially acknowledged the new price tag at the same time it conceded that there was a crucial mistake in its economic forecasts that was leading the agency to dramatically overestimate its future sales tax revenue.

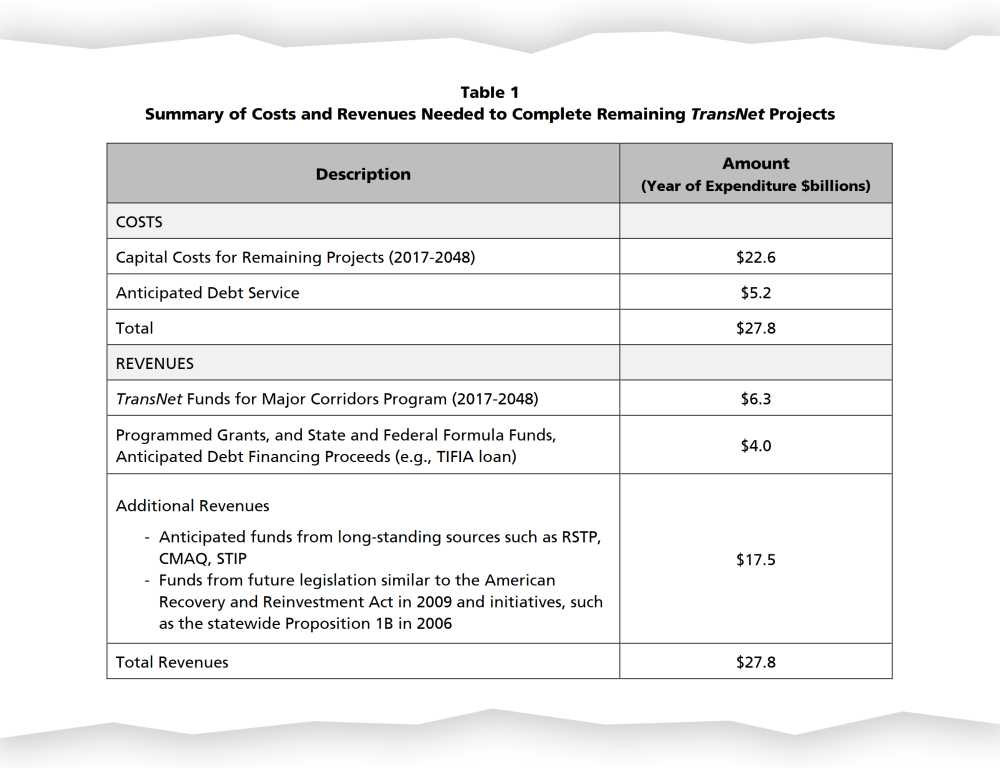

Together, the two errors have opened up a $17.5 billion shortfall in TransNet. SANDAG will now need to collect that money from state and federal sources, pass a new tax to cover the difference or scale back the promises made to voters who approved TransNet 12 years ago.

Agency leaders claimed throughout 2016 that Measure A, combined with state and federal funds, would have built another wave of regional transportation projects throughout the county, in addition to those still to be built in TransNet

Nothing, however, would have prevented the new Measure A funds from paying back the old TransNet obligations. Failing to disclose the increased costs in TransNet, and overestimating the anticipated revenues from both taxes, obscured the extent to which that was a distinct possibility.

SANDAG officials pointed to a rolling TransNet financing outline that indicated the program was on track to make good on all of its promises.

But it was that outline, in January 2016, that relied on project cost estimates that SANDAG itself had already changed.

That is incorrect. The plan did not rely on the most recent project cost assumptions for those projects.

Months earlier, in October 2015, SANDAG updated the cost estimates for every project it’s planning to build – including those in TransNet, and many for which it hasn’t locked up a funding source.

That’s when SANDAG approved a new, long-term plan for the region’s transportation needs, called San Diego Forward. Part of that process includes updating all of the cost estimates of projects included in the plan.

But SANDAG did not use those newly updated costs three months later, when it updated the financing plan that tracks whether TransNet was is still poised to meet its obligations.

Instead, it waited until December 2016 to finally incorporate the new project costs. Doing so increased the overall cost of the program by $8.4 billion.

In SANDAG’s own words, it knew in October 2015 when it adopted a new regional plan that the cost of TransNet had increased significantly. It nonetheless continued to rely on out-of-date estimates that made the program appear cheaper for more than a year.

“The more current cost estimates are derived from figures included in San Diego Forward: The Regional Plan, adopted by the Board in 2015,” read a staff report for that meeting. “Previous cost estimates were derived from estimates developed as part of the TransNet Extension approved by voters in 2004.”

Projects get more expensive in two ways. Their price tag can increase due to changes in inflation or the cost of construction.

They can also get more expensive, however, as staff does more work on the project and recognizes new issues that need to be addressed – things like engineering problems, local opposition to a rail alignment or discovering a sensitive species in a habitat the project will pass through.

In a statement, SANDAG said its TransNet Plan of Finance was simply taking old project costs and adjusting them for changes in construction costs. The agency’s regional plan took everything into account, which is why its numbers were much higher.

“Staff had historically used a different methodology for calculating the estimated costs of TransNet projects,” spokesman David Hicks wrote in a statement. “Essentially, the original project cost estimates developed in 2002 in preparation for the TransNet Extension were escalated each year based on inflation. It’s important to note that projects envisioned in the Regional Transportation Plan can evolve and expand as the plan is updated every four years, but the original TransNet project obligations remain the same.”

After Measure A failed, board members asked the agency to provide another status update on TransNet, Hicks said.

“The report included updated estimates of future revenue and updated project costs,” he wrote. “The estimated project costs in the Regional Transportation Plan had diverged over time from the escalated costs of the original estimates (as more detailed design and engineering was done, technology evolved, additional scope was added to projects in the regional plan, etc.).”

That’s when the cost of completing TransNet jumped by $8.4 billion. Specific projects, like a high-frequency bus line in the South Bay, increased in cost from $110 million to $206 million in one shot.

Stewart Halpern, chair of the committee created specifically to oversee TransNet, could not be reached for comment.

Peter Kiernan, an attorney with Schiff Harden who specializes in public finance and infrastructure and who worked as special counsel on those issues for the city and state of New York, said the methodology SANDAG had previously relied on seemed to suggest they had been lowballing project costs all along.

“They did not use best practices,” Kiernan said “You could give them the benefit of doubt and say they made a mistake, or you could be less generous and say they deliberately misled or invited skepticism. In any event, there’s a lacking there and it’s appropriate to point it out.”

He said the mistake is especially egregious because it happened in the run-up to a public vote on a related matter.

“It sounds like they didn’t meet their basic duty to present the best possible information to voters,” Kiernan said. “There’s two groups of people who should be outraged – the board, and the voters.”

José Nuncio, TransNet’s program director, offered another explanation for why the agency didn’t include the most up-to-date costs in the program’s spending plan.

Underestimating the costs, Nuncio said, allowed the agency to show it was on track with all of the projects it hoped to build. By showing that those projects were still on track, the agency could keep doing prep work on them – things like preliminary engineering, environmental surveys and public outreach.

By doing that work, the agency could get the projects to eventually be considered “shovel-ready.” State and federal grant-makers look for shovel-ready projects when they have funds to offer.

In other words, underestimating the costs, Nuncio said, put the agency in a position to be more competitive for outside funding sources than it would have been if it had used the real project costs.

When SANDAG finally acknowledged the real costs for the remaining Transnet projects, it did so at the same time it acknowledged the forecasting error that produced unreliable revenue expectations.

Since that revenue problem had already been in the news, that’s what got the attention – including from Voice of San Diego, which had previously reported the problems with the agency’s revenues.

[divider] [/divider]