CalPERS delayed action last week on the chief actuary’s proposal to shorten the period for paying off new pension debt from 30 years to 20 years, a cost-cutting reform that would end the current policy not recommended by professional groups.

The reluctance to impose a small short-term rate increase on struggling local governments may signal that the CalPERS board will not make a major shift of investments next month that would trigger the fifth employer rate increase since 2012.

Officials from two dozen cities and their associations told the board that rate increases are severely squeezing local government budgets. Most opposed the shorter debt payment period and two proposed investment reallocations that would raise rates.

“The common theme that you will hear is that the employer-pays-more option is simply no longer a viable option,” Dane Hutchings of the League of California Cities told the board last week. “The well is running dry.”

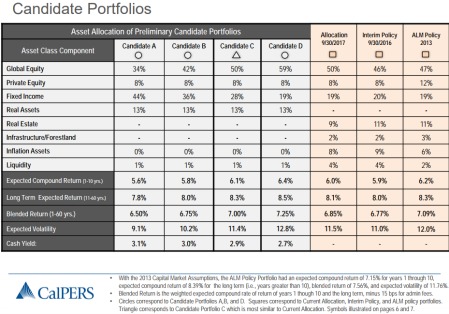

The cities urged the CalPERS board to choose an investment portfolio allocation next month that would leave the current earnings forecast at an annual average of 7 percent, avoiding a rate increase.

Two options with less risky but lower-yielding investments would cut expected earnings used to discount future pension obligations to 6.75 or 6.5 percent. To close the funding gap created by the forecast of lower earnings, employer rates would be raised.

The investment allocation decision next month follows a lengthy review done every four years. But last December the California Public Employees Retirement System broke the usual four-year cycle by dropping the earnings forecast from 7.5 to 7 percent.

The rate increase won’t be fully phased in until 2024. Some say the 7 percent forecast is too high. CalPERS experts predicted the portfolio would earn 6.2 percent next decade, before averaging more than 7 percent during the following two decades.

CalPERS also broke the four-year cycle by shifting to less risky but lower-yielding investments in September last year. By January, the rare attempt at market timing had cut earnings by $900 million as stocks began a post-election runup.

The unusual CalPERS moves last year — cutting investment earnings expected to pay 60 percent of future pensions while raising employer rates to get more money — resulted from the failure to recover from huge investment losses a decade ago.

Last year CalPERS had 68 percent of the projected assets needed to pay promised pensions, little changed from a low of 61 percent in 2009. Now after a lengthy bull market that tripled major stock indexes, some expect a correction or downturn.

Lacking the traditional cushion of 80 percent or more funding, CalPERS fears that another market crash like the financial crisis a decade ago could drop the funding level below 50 percent, a red line some experts say makes recovery very difficult.

So, instead of taking on more investment risk to increase earnings and the funding level, CalPERS went the other way, reducing risk and earnings to decrease the odds of funding dropping below the 50 percent red line.

Last week, some cities warned of their red line by repeating that the “employer-pays-more option is no longer viable”. With the exception of new hires since a reform in 2012, employee contributions are frozen, set by statute and protected by court decisions.

Scott Terando, the new CalPERS chief actuary appointed in January, told the board the current actuarial policy of delaying debt payment is one reason the funding level did not recover after the financial crisis.

CalPERS was 100 percent funded with investments valued at $260 billion in 2007, before plunging to 61 percent funded and investments worth about $160 billion in early 2009. The investments were valued at $343 billion last week.

Until a reform in 2013, CalPERS had spread the recognition of investment gains and losses over 15 years, far beyond the 3 to 5 years used by many pension plans. The lengthy “smoothing” period avoided jumps in employer rates, but also delayed debt payment.

CalPERS also had been using “rolling” or “open” amortization to pay off the debt or “unfunded liability” from investment returns below the annual earnings forecast, now 7 percent. The debt was refinanced annually and theoretically might never be paid off.

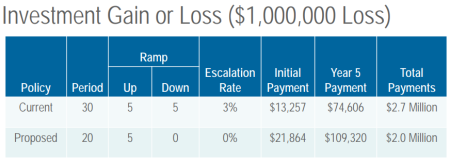

The reform in 2013 pays off debt from below-target investment earnings over 30 years. Employer rate increases are gradually increased during a five-year “ramp up” and remain at the full amount for 20 years, before a five-year “ramp down” ends the payment.

“So, what happened is we moved a notch from basically ‘unacceptable’ to ‘not recommended,’ and that’s where we are today,” Terando said, referring to guidelines from the California Actuarial Advisory Panel and several other professional groups.

Most California public pension systems are said to use the recommended 15 to 20-year payment periods. Among 17 systems listed in a staff report only the Los Angeles County Retirement Association had a 30-year payment period.

Under the current CalPERS 30-year payment policy, the debt continues to grow for the first nine years. The payment is not large enough to cover the interest, the amount that could have been earned if the debt were invested and yielded the earnings forecast.

Actuaries call that “negative amortization.” And under the current CalPERS 30-year policy, the payments do not begin reducing the original debt until year 18, more than halfway through the period.

“So, you make 18 years of worth of payments and you are right where you started from,” Terando said. “That’s kind of the reason our funding status has remained flat while our assets have grown.”

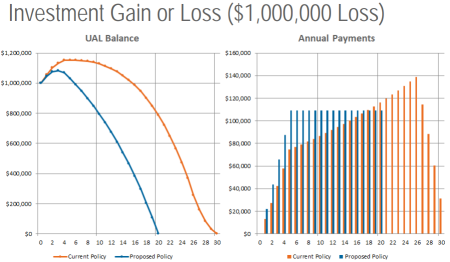

Current CalPERS policy uses a “level percentage” of payroll payment. For example, 3 percent of pay becomes more costly as payrolls grow over the years. Terando is proposing a “level dollar” payment that does not grow with the payroll. (see chart below)

The proposed 20-year payment period saves money. The total payment for a $1 million investment loss is $2 million, compared to $2.7 million under the 30 year plan. Less debt is pushed to future generations. The funding level recovers faster.

But employer rates are likely to increase, probably for the first two years, Terando told the board. CalPERS employer rate increases can face resistance from unions, who argue that taking money off the bargaining table should be negotiated.

Last week, board members cited city opposition to another rate increase as they suggested alternatives to Terando’s proposal: waiting until the 3-year phase in of the 7 percent discount rate is completed, only switching to level dollar payments, hardship exceptions, and a 25-year period.

Rob Feckner, board president, thanked Terando for his professionalism and standards. He said in a “perfect world” CalPERS should start paying off the debt from investment losses in the recommended 15 to 20-year period.

“Somehow we need to be able to find an area where we can give them (local governments) options, instead of us being the hammer because it’s not going to be a pretty picture,” Feckner said.

CalPERS encourages local governments to make extra payments to pay down debt faster. A city-backed request to analyze cost-cutting suspensions of COLAs and lower future pension earnings for current workers was rejected by the CalPERS board in September.

Richard Costigan, finance committee chairman, said there will be a workshop and a survey of employers before the committee considers Terando’s proposal again in February, a delay in action originally scheduled for next month.

[divider] [/divider]