By Ed Mendel.

A new report shows a third of local governments in CalPERS will have police and firefighter employer rates next fiscal year that are at least 50 percent of pay, a level that a former CalPERS chief actuary believed a decade ago would be “unsustainable.”

At the high end, the number of local governments with rates of 70 percent of pay or more (all of them cities except for one special district) will increase from 15 this fiscal year to 24 in the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

The average “safety” or police and firefighter employer rate will increase 4.75 percent next fiscal year, going from 44.23 percent of pay now to 48.98 percent next July, said the annual CalPERS Funding Levels and Risks Report given to the board last week.

The average safety rate is projected to continue to grow, up from 44.23 percent of pay this year to 55 percent of pay in 2024. Rates for at least one large city, Santa Ana, are expected to increase from 72.6 percent of pay this year to 100 percent of pay in 2024.

“The greatest risk to the system continues to be the ability of employers to make their required contributions,” said the new report.

With a few exceptions, employers are making required monthly payments to CalPERS on time. But the ability to absorb high rates varies widely among the 1,578 “public agencies” in the system: cities, counties, and special districts.

The report said there is evidence some public agencies are “under significant strain,” citing collection activities and requests for longer debt-payment periods and for information about leaving CalPERS.

After the CalPERS investment fund plunged from $260 billion to $160 billion in the financial crisis and stock market crash a decade ago, the CalPERS chief actuary then, Ron Seeling, issued a warning at a Retirement Journal seminar in August 2009.

Seeling said his personal belief was that CalPERS was facing “unsustainable pension costs of between 25 percent of pay for a miscellaneous (nonsafety) plan and 40 to 50 percent of pay for a safety plan . . . We’ve got to find some other solutions.”

The CalPERS investment fund, doubling since the crash, was $347 billion last week. But pension debt or “unfunded liability” grew faster, driven by investment losses, longer lifespans, and a drop in the earnings forecast used to discount debt to 7 percent.

Now the CalPERS systemwide average funding level, 100 percent before the crash, is only 71 percent of the projected assets needed to pay the future pension costs of a growing number of retirees.

The low funding level, well below the traditional 80 percent minimum, is slim protection against a market crash or slump that drops funding below 50 percent, a red line experts say makes recovery to 100 percent difficult if not impractical.

CalPERS seems to have few workable options to improve its funding level, other than to continue to assume long-term investments will solve the problem, even though critics say a 7 percent earnings forecast is too optimistic.

Another employer rate increase, as previous hikes are straining local budgets, would be difficult. Higher employee rates, now about 10 to 15 percent of pay for safety workers, must be bargained with unions and may have limits.

Gov. Brown’s cost-cutting pension reform in 2013 for new hires will take years to have a modest impact. CalPERS expects the reform to save $29 billion to $38 billion over 30 years, a small reduction in a $138.6 billion unfunded liability as of June 30, 2016.

A major reform proposed by the bipartisan watchdog Little Hoover Commission in 2011, going beyond new hires, would allow cuts in the pensions earned in the future by workers hired before the Brown reform, while protecting amounts already earned.

But under a series of state court decisions known as the “California rule,” the pension ofered at hire becomes a vested right that can’t be cut unless offset by a comparable new benefit, erasing the savings.

The state Supreme Court has scheduled a hearing Dec. 5 on a case some think may modify the California rule. After a 14-month delay, Brown filled a vacant Supreme Court seat last week by appointing his legal advisor, Joshua Groban.

Brown said last January he has a “hunch” the courts will modify the “California rule,” so “when the next recession comes around the governors will have the option of considering pension cutbacks for the first time.”

Among the number of local governments that have raised taxes to help cover the growing cost of CalPERS pensions, the small city of Oroville has been one of the most forthright, warning that the alternative could be bankruptcy.

As cities lined up at a CalPERS board meeting last fall to ask for relief from rising pension costs that are forcing cuts in staff, pay, and services, the Oroville finance director, Ruth Wright, told the board, “We have been saying the bankruptcy word.”

Wright said the city had recently negotiated a 10 percent pay cut with police, the workforce had been cut by a third two years earlier to help balance the city budget, and the “cash flow” would be gone in three or four years.

This month Oroville voters approved a 1-cent sales tax increase, after rejecting a similar proposal two years ago, as well as a 10 percent tax on marijuana businesses, which have not yet opened pending approval by the city.

Previous bankruptcies have shown that cities may be unlikely to cut pensions, particularly for vital police and firefighter services, even if the California rule is modified by the state Supreme Court.

Officials in Stockton, a city with a high crime rate, said from the outset of bankruptcy they would not cut pensions, needed to be competitive in the job market. But the Stockton case did produce a federal court ruling that CalPERS pensions can be cut in bankruptcy.

San Bernardino had the strongest case for cutting pensions. The city filed an emergency bankruptcy in 2012, somehow surprised to learn that it would soon be unable to meet payroll, and then skipped contract-required monthly payments to CalPERS for a year.

“The city concluded that rejection of the CalPERS contract would lead to an exodus of city employees and impair the city’s future recruitment of new employees due to the noncompetitive compensation package it would offer new hires,” San Bernardino said in a court filing two years ago, echoing Stockton’s position.

“This would be a particularly acute problem in law enforcement where retention and recruitment of police officers is already a serious issue in California, and where a defined benefit pension program is virtually a universal benefit.”

Vallejo officials said consideration of pension cuts was deterred by a CalPERS threat of a costly legal battle. Like San Bernardino, Vallejo still has to close recurring budget gaps and faces high CalPERS safety rates next year: San Bernardino 82.6 percent of pay, Vallejo 78 percent.

Stockton, with a CalPERS rate of 59.7 percent of pay, looks like success to some. A national nonprofit organization, Truth in Accounting, ranked Stockton No. 2 among the nation’s most populous 75 cities in terms of fiscal health, based on debt or surplus per capita.

“According to its research, Truth in Accounting found that Stockton has a surplus of $3,000 per resident, and gave the city a “B” on its grading scale,” the Stockton Record newspaper reported last May.

The new risks report shows that local governments have a wide range of CalPERS pension costs. Actuaries attribute much of the difference to varying payrolls and other factors, some of them large such as a police or firefighter unit transferring to another system.

CalPERS encourages employers, if able, to make additional contributions to lower their risk of lower funding and higher future contributions. Last year 195 employers contributed a total of $538 million, up from 185 employers and $228 million in the previous fiscal year.

A generous police and firefighter pension formula, geared toward early retirement from strenuous jobs, has a much higher cost than the “miscellanous” pensions for nonsafety employees.

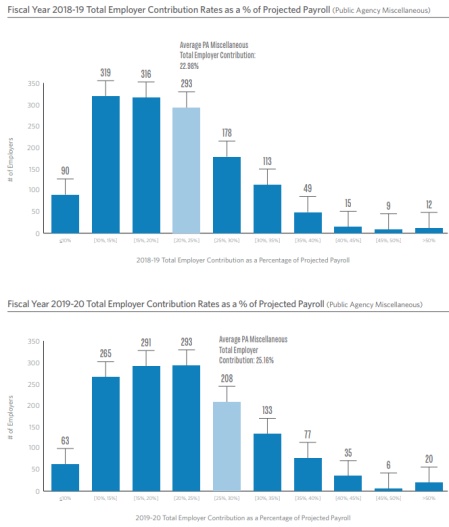

But the new risks report shows that the average CalPERS miscellaneous rate will reach the level the former chief actuary believed would be unsustainable: 25.16 percent of pay next fiscal year, up from 22.98 percent this year.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Cal Pensions.