The mayor has touted record investments in infrastructure and a 2016 measure sends more money to pay for projects, yet the city’s five-year shortfall to fund projects is $286 million higher than the previous year.

The city of San Diego will face at least $1.86 billion in various infrastructure needs over the next five years with no concrete plan to pay for them, city projections show.

The city’s five-year infrastructure funding shortfall is $286 million higher than it was a year ago, despite the passage of a 2016 ballot measure that sends more tax money to infrastructure projects. But even that underestimates the extent to which things are getting worse. The shortfall this year for the first time includes a conservative estimate of how much developers could pay for infrastructure improvements in the coming years. Even including that revenue source for the first time, the shortfall still grew.

Proposition H, the measure passed in 2016 that went into effect in 2018, is providing an average of $19.67 million annually for city infrastructure projects, not enough to make a meaningful dent in the backlog, city data shows. Neither will the upcoming 2020 convention center measure voters may consider in March.

The total gap is the result of $5.6 billion in city infrastructure needs meeting just $3.8 billion in funding over the next five years. Projects needed are diverse and include things like repairs to sidewalks and aging buildings, as well as new streetlights, bike facilities and libraries.

Here is a closer look at each year’s funding gap as reported in the city’s latest infrastructure outlook report, with a reference line for average Prop. H revenue so far.

The impact of Prop. H is “very minor,” said Jeff Kawar, deputy director of the city’s Office of the Independent Budget Analyst. The formula will change and a portion of “Prop. H is going to go away in the next couple years, and even if the Convention Center measure passes, it provides nothing in the first five years.”

If approved, the Convention Center measure will stow away some hotel taxes for street repairs, but not for the first five years. Even when street funding does start to flow in year six, the measure is projected to bring in just $7 million at the start, and a total of $546 million over the 42-year life of the measure, according to numbers seen by the Office of the Independent Budget Analyst last fall.

That’s not even a third of the money needed in the next five years, let alone the next 42.

“Any new money is great. But it’s not the answer,” said Andrea Tevlin, the city’s independent budget analyst. “What is needed to do anything meaningful now is a new source.”

Still, Mayor Kevin Faulconer sees value in the potential new dedicated funding stream.

“The Citizen’s Initiative that’s up for a vote in March sets aside considerable funding dedicated specifically for road repair, and prohibits that funding from being used for any other purpose, with criminal penalties for those who misuse the funds. This ensures that future leaders cannot leave our city in a state of disrepair,” he said in a statement Thursday.

♦♦♦

City officials have touted record spending on infrastructure in recent years.

“This plan builds on the progress we’ve made over the past few years to put neighborhoods first and delivers the largest infrastructure investment in city history,” Faulconer wrote in a June 10 press release about the 2020 budget approval.

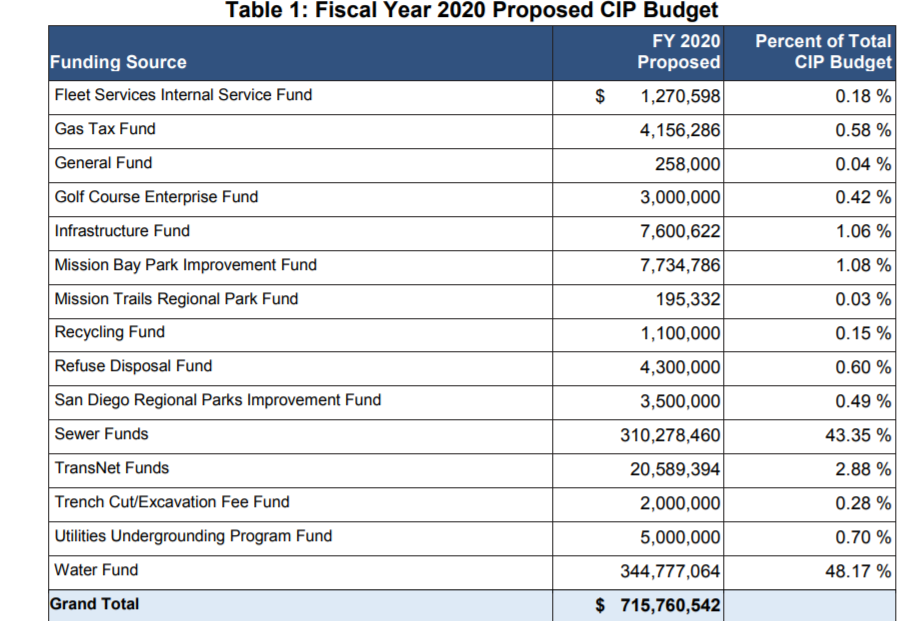

As it turns out, the bulk of the city’s infrastructure spending comes directly from consumer and developer fees or dedicated outside sources, not the discretionary pot of tax money kept in the city’s general fund. The mayor’s proposed budget would have spent just $258,000 from the general fund on capital projects in 2020, records show.

The budget was amended in May, increasing general fund spending to nearly $1.86 million, but it still only makes up a small fraction of all infrastructure spending planned in 2020.

Water and sewer funds make up more than 91 percent of the funding in this year’s capital improvements budget.

The city’s multibillion-dollar Pure Water sewage purification project, for instance, will raise customer bills to achieve its goal of providing a third of the city’s drinking water by 2035 – although that project is now facing litigation delays. Currently, the city anticipates a dip in its overall infrastructure needs after 2021, when phase one of the project is supposed to be complete, but delays could change that.

Ashley Bailey, spokeswoman for Faulconer, said it is still fair to tout this year’s budget for record infrastructure spending, because city leaders are the ones who raised customer rates to pay for projects.

“Water and sewer fees, just like general fund dollars, are put toward infrastructure projects through the conscious decisions of City leaders. For example, the City Council could have chosen not to increase water and sewer rates. But they did, and that decision helped grow the water and sewer budgets to their current levels, which in turn is helping to replace water mains, fund the Pure Water project, and complete other system improvements,” she said.

Faulconer acknowledged more revenue is needed in both the short- and long-term, in spite of Prop. H money and the possibility of new funds from a Convention Center measure.

“Decades of neglect by past city leaders left San Diego with a long list of underfunded infrastructure needs,” he said in a statement. “With each budget since 2014, we’ve continually increased the dollars going to capital improvements – to its now all-time high of $710 million. And with the help of Proposition H, the city’s road paving crews are busier than ever before. The fact is though that it’s still not enough.”

♦♦♦

There’s no doubt Faulconer has made headway on repaving streets, and that momentum is expected to continue. Street repaving projects will be fully funded and cost more than $222 million over the next five years, according to the city’s projections.

“Road conditions affect every San Diegan in every community, so the City’s highest

infrastructure priority remains street repair,” Faulconer‘s latest budget reads.

Still, street and road modification needs – beyond repaving – are left unfunded by $59 million in the next five years, city numbers show.

Multiple factors are hurting the city’s progress.

With state money available following the gas tax increase in 2017, there’s more competition among local governments for slurry seal road repair work, said James Nagelvoort, the city’s director of public works.

Nagelvoort told the city’s infrastructure committee on Jan. 30 that contractors are also factoring in higher material costs in anticipation of the impact of new tariffs imposed by the federal government.

“It’s not necessarily that we need more. It’s that the projected cost of what that (backlog) is has gone way up,” Nagelvoort said. A lack of skilled laborers for “vertical” projects like buildings and bridges, also poses problems, he said.

Also limiting the city’s progress is the age of city buildings, most of which were built in the 1960s and ‘70s. Every year, the city is seeing a greater volume of buildings needing repair.

“As we project out into the future, you are going to see more and more assets reaching the end of their useful life,” Nagelvoort told the committee.

Existing city facilities are the second-highest unfunded need, making up $251.5 million of the five-year gap, according to the city numbers.

Jillian Kissee, a fiscal and policy analyst in the budget analyst’s office, said adequate upkeep is also necessary to prevent things from getting worse.

“The longer you don’t take care of maintenance, it becomes a capital problem.”

***

Over the five-year period from fiscal year 2020 to 2024, stormwater needs take the cake as the biggest unfunded need, making up nearly $720 million of the total $1.86 billion gap.

The city auditor criticized city leaders last year for not addressing the city’s stormwater needs, saying a failure to act can pollute streams and coastal waters, and lead to flooding and sinkholes.

To help address stormwater needs, the budget analyst office recommends the City Council explore an increase to the existing 95 cent storm drain fee to something closer to what other cities charge – which may add several dollars.

The city auditor and an outside study done in 2016 recommended the same thing.

“We believe that is one avenue that can be addressed,” Tevlin said.

Existing facilities follow as the next largest unfunded need, followed by streetlights at nearly $202 million, city projections show.

Here’s the breakdown of the $1.86 billion five-year shortfall.

“The report here is sobering, because the numbers are enormous,” City Councilman Mark Kersey, who chairs the city’s infrastructure committee, said on Jan. 30. “On the general fund side, we are a little bit short. In fact, we are a lot bit short when it comes to being able to fund the various projects that we need done.”

“Even though we have made a lot of progress on infrastructure and rebuilding San Diego, there is still plenty of work to do. This is not something we will ever finish,” he said.

Councilwoman Vivian Moreno, who also sits on the committee, asked Kersey to bring back revenue options to close the $1.86 billion gap.

“This gap is never going to close on its own,” Moreno said. “If we could continue to produce these outlooks that show a funding gap, yet fail to take action to close the gap, then the outlook process becomes – with all due respect – an empty exercise.”

Kawar, the IBA deputy director, said in recent years infrastructure “went from top priority” to less of a priority, as more focus turned to the city’s homeless and affordable housing needs, and more recently, transportation.

“These are all competing for the same scarce resources,” Kawar said.

San Diegans are already slated to vote on various tax measures in 2020, including the Convention Center, affordable housing and transportation.

Discussion has not yet returned to the idea of a city “megabond” dedicated to infrastructure that could make a considerable dent in the city’s backlog. Such a measure was previously considered for the 2016 ballot, but ditched in favor of Prop. H.

“Voters have a limited appetite,” Tevlin said. “I do think there will be movement in the next couple years. … This is not a good time right now, but it will have to come in the future.”

[divider] [/divider]