By Nancy Scola.

Protected bike lanes — a.k.a. “cycle tracks,” or “green lanes” for the color they’re often painted — are far rarer in the United States than they are in Europe, and U.S. cities, says Christopher Monsere, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Portland State University, are holding off on creating them until they better understand how they fit into urban traffic flow. Monsere and a team of 10 other researchers recently examined how protected lanes work in Austin, Chicago, Portland, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., and found that while Americans generally support green lanes, understanding how those lanes are perceived — by cyclists and drivers — is critical for promoting future citywide acceptance.

One reason why protected bike lanes haven’t gotten more traction, suggests Monsere, is that the civil engineers involved in designing city streets have tended to be “vehicular cyclists” — or road riders accustomed to mixing with on-street traffic. “They didn’t think that on-street facilities of any kind were good to begin with,” explains the professor, “and that [green lanes] are even worse, because they put cyclists out of the space where drivers would see them. They’d forget about them, and at the intersections it would cause all kinds of chaos.”

But the researchers studied 168 hours of footage from the five cities’ lanes — a full week’s worth of around-the-clock viewing — that captured the intermixing of nearly 17,000 bicyclists and 20,000 cars but little chaos: Not only were there no recorded collisions, but no recorded near-collisions either. “Intersections are still the riskiest part” of bike lanes, says Monsere, “and there are improvements and tweaks that could be done, but we saw no reasons for concern.” (The cities examined by the multi-year study are taking part in the non-profit group People for Bikes’ “Green Lane Project.”)

The Portland State team talked to the cyclists, too, and across the board about a quarter of the riders said that they were riding their bicycles more because of the new presence of the protected lanes; that rate varied from 19 percent on San Francisco’s Oak Street path to 54 percent on Chicago’s Dearborn lane.

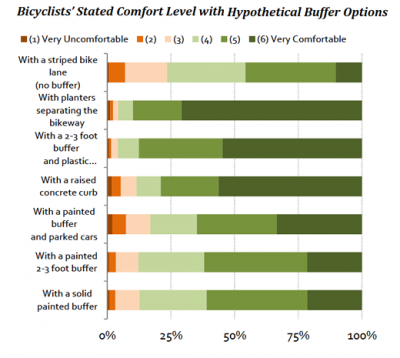

The researchers also asked riders they intercepted how safe they were made to feel by various methods for separating bike traffic from car traffic. (People for Bikes identifies 14 different design options, from simple striping to “turtle bumps” to barriers made up of parked cars.) Physical barriers, not surprisingly, made riders feel more secure than mere painted ones. But there are hints that if cities are aiming to up ridership by upping safety, perception matters considerably. Says Monsere, “The flex post,” as in a plastic pole that delineates the edge of the bike path, “came out relatively high even though it provides no diversion from vehicles at all.”

The researchers found that the vast majority of the general public — drivers, walkers, transit-takers, bicyclists, those who mix modes — back the premise of the green lane. Some 91 percent of residents surveyed by the researchers agreed with the statement, “I support separating bikes from cars.”

But residents, found the study, were more split on the idea that the protected bike lanes up the appeal of their neighborhoods. Some 43 percent of those asked said that the presence of protected lanes for cycling made their neighborhood “more desirable,” while an equal percentage said that they had no effect. And 14 percent said that having green lanes made where they live less desirable.

One reason that locals might not be more thrilled about protected bike lanes is parking. Across the cities, some 30 to 55 percent of drivers reported that the lanes limited their parking options. But here’s the kicker: That occurred even in cases where the addition of the lanes has limited effect or no effect on parking. Indeed, finds the study, some 30 percent of residents around Portland’s Multnomah lane reported that “the lane made parking more difficult to find,” even though when adding the lane the city also added some 27 parking spaces.

All of which serves to remind city planners that the future success of protected bike lanes in the United States doesn’t just depend on adding some green paint, but on what people think of when they see it.

[divider] [/divider]

Originally posted at Next City.