An old line about local governments in CalPERS — “You can check in, but you can’t check out” — usually refers to an often prohibitively high termination fee to pay future pension costs.

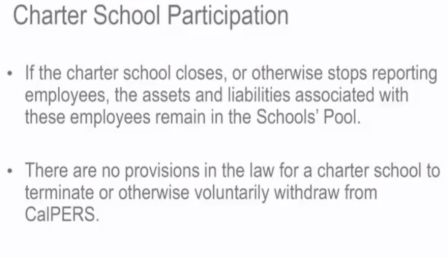

But for charter schools the old line is literally true. Current law does not allow termination of their CalPERS contract. When a charter school closes, the unpaid pension debt is covered by the large CalPERS pool mainly funded by regular schools.

CalPERS has contracts to provide pensions for non-teaching employees in 422 charter schools, a growing movement that allows parents to choose a state-funded school operating free of many state regulations. Thirteen more charter schools are seeking CalPERS contracts.

A few charter schools have gone into bankruptcy. Some charter school operators have been convicted of wrongly using public funds for their own purposes. And about 600 have closed or never opened since charter schools were authorized in 1993.

CalPERS enrolls charter school employees through contracts with county offices of education. There are signs that some charter schools in CalPERS may be having trouble or want to shed growing pension costs.

“CalPERS has identified an estimated 140 charter schools that have stopped reporting payroll to us,” Amy Morgan, a California Public Employees Retirement System spokeswoman said last week.

“CalPERS is analyzing this information and is working on developing a process to improve compliance with reporting payroll for these charter schools,” she said.

Last year CalPERS received its first charter school requests about termination. They came from Aspire, which has three dozen charter schools in several counties, and King-Chavez, which has six charter schools and two preschools in San Diego County.

The King-Chavez chief executive, Tim Wolf, was unpleasantly surprised last week when asked about a CalPERS report that King-Chavez “does not report payroll and may be closed,” which CalPERS later acknowledged was erroneous.

“We are continuing to contribute to CalPERS and are only seeking information regarding our future option,” Wolf said.

Over the last 15 years, he said, state funding has not kept pace with the cost of the total benefit package that grew from 14 percent of pay to 40 percent of pay. Half of the cost is for CalPERS and CalSTRS, half for medical, dental, workers compensation, and other things.

“Aspire continues to report payroll,” CalPERS said. Aspire did not respond to a request last week about its future pension plans.

When a charter school closes, its unpaid debt or “unfunded liability” for future pension costs are covered by the large CalPERS pool for all schools. CalPERS said it had no breakout for the amount of debt left in the schools pool by closed charter schools.

The pensions of closed charter schools employees are not cut to cover the unpaid debt, as happened last year to 182 former employees of a closed job-training agency, LA Works, also known as the East San Gabriel Valley Human Services Consortium.

Four cities that formed the joint powers authority declined to pay a $19.5 million termination fee. To cover the debt, CalPERS cut the pensions of the former LA Works employees, 74 already retired, by 63 percent, recently reduced to 58 percent.

CalPERS once had the option to use its Terminated Agency Pool, if a surplus allowed, to cover the unpaid debt of employers, avoiding pension cuts. But CalPERS had ended that seldom-used policy before it was eliminated by legislation this year.

At a CalPERS finance committee last April two board members said the question of whether regular schools should pay the pension debt of closed charter schools is a concern. (See video starting at 2:08)

“It shouldn’t be all the other school districts responsibility to pay for that chartering agency’s decision,” said board member Rob Feckner. “So I think it should fall back on that chartering agency, and that county office of education, to make whole not the schools pool.”

Outgoing board president Priya Mathur said whether public schools should be responsible for charter school pension debt is a big policy question. “It’s not really a CalPERS question in terms of making our members get their benefits paid for,” she said.

Matthew Jacobs, CalPERS legal counsel, told Mathur: “That is exactly the type of conversation that we have been having with stakeholders to make sure that they are aware of the issue and, hopefully, take action to address it.”

At this time, CalPERS is not talking to stakeholders or pursuing legislative strategies on the payment of charter school debt by the schools pool, Morgan, the CalPERS spokeswoman, said last week.

The California State Teachers Retirement System tightly monitors charter schools by tracking changes in their payrolls and by developing an audit system to identify high-risk charter schools.

CalSTRS also has the authority, unlike CalPERS, to recover unpaid charter school debt by asking the state controller to withhold payment to county education offices or other agencies that report payrolls and send contributions. The authority was used for the first time last January.

The operator of two Livermore charter schools, Tri-Valley Learning Corp., declared bankruptcy last year. To recover its unpaid June contribution, CalSTRS had the controller withhold $53,000 from the January payment to the Alameda County Office of Education.

Alameda officials urged CalSTRS to reconsider, arguing that the withholding law did not apply in this situation, the charter authorizing agency was the Livermore Unified School District, and that a better statewide solution to charter school bankruptcies is needed.

“We need a strategy for collecting delinquent contributions that holds the right parties responsible,” Karen Monroe, superintendent of the Alameda County Office of Education, told the CalPERS board in February.

She said allowing charter schools to shift CalSTRS obligations to public agencies creates “perverse incentives,” makes it difficult to collect delinquent payments, and could impact authorization of new charter schools by creating new concern about the financial risk.

Monroe said her office was willing to work with CalSTRS on changes, including some CalSTRS is already considering such as escrow accounts, bonding or insurance, and making the county office of education the charter school reporting agency optional.

As for the $53,000 payment withheld in January: “We are still in conversations with CalSTRS to resolve the issue,” Michelle Smith McDonald, Alameda County Office of Education spokeswoman, said last week.

Another CalSTRS charter school issue surfaced last year. The number of new charter schools that did not choose CalSTRS had been about 10 percent for eight years, before falling in fiscal 2014-15 to 20 percent and in 2015-16 to 33.3 percent.

The decline in charter schools choosing CalSTRS may have been influenced by legislation in June 2014 that raises school district CalSTRS rates from 8.25 percent of pay to 19.1 percent of pay by 2020.

Of the 1,239 California charter schools operating as of last June, about 86 percent or 1,070 are in CalSTRS, said Michael Sicilia, CalSTRS spokesman. The total number of charter school employees last fiscal year is an estimated 30,000.

Because CalSTRS had 445,935 active members making contributions to the pension fund last year, the small loss of new charter school members so far has little impact on rates paid by school districts.

An update of the number of new charter schools that choose CalSTRS is being prepared for the CalSTRS board meeting Nov. 7-9 and may be posted later this week, Sicilia said.

[divider] [/divider]