A new labor contract negotiated by the leaders of a 95,000-member state worker union has a pay raise that, an opposition group said last week, is more than offset by medical costs and Gov. Brown’s push to have workers begin paying toward their retiree health care.

Most state workers contribute 5 to 11 percent of their pay toward their CalPERS pensions, while most state employers contribute 27 percent of pay. The Highway patrol has the highest employer contribution, 50 percent of pay, and an employee rate of 11.5 percent of pay.

But only state employers have been paying for retiree health care during its rapid growth. Until recently, state workers have not paid for a remarkably generous retiree health plan that actually pays more of their health care premium when they retire.

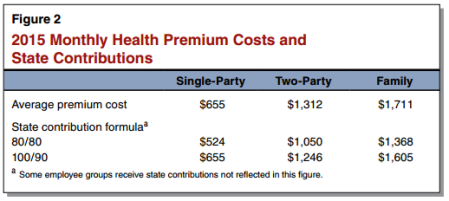

While on the job, the state pays 80 percent of the health care premium for most state workers and their dependents. When most retire, the state pays 100 percent of the average individual premium and 90 percent for dependents, which last year was $1,605 a month.

How did what Brown has called an “anomaly” happen?

Some trace it to a cost-cutting move more than two decades ago by the administration of former Gov. Pete Wilson. Active workers were required to begin paying some of the cost of their health care. No change was made for retiree health care.

At about the same time, legislation by former Assemblyman Dave Elder, D-Long Beach (AB 1104 in 1991) created a fund in the state treasurer’s office to begin “prefunding” state worker retire health care.

Annual payments from the state and workers could go into an investment fund to help cut the long-term cost of retiree health care. Investment earnings are expected to pay two-thirds of the cost of California Public Employees Retirement system pensions.

Prefunding retiree health care also would improve “intergenerational equity,” the fairness principle that public services should be paid for by those that receive them not passed on to future taxpayers. (See previous post: “How pensions pass the buck to future generations”)

But lawmakers had other priorities, and they chose not to put money in the state worker retiree health care fund created by the Elder legislation. Pay-as-you-go state worker retiree health care would go on to become one of the fastest-growing state budget costs.

The state paid $458 million in 2001 (0.6 percent of the general fund) for state worker retiree health care and this fiscal year is expected to pay $2 billion (1.7 percent of the general fund), according to the Finance department. The state payment for CalPERS pensions is $5.4 billion.

Now pay-as-you-go state worker retiree health care, unaided by investment earnings, has created a long-term debt for state worker retiree health care that is larger than the debt for state worker pensions.

The estimated debt or “unfunded liability” for retiree health care promised state workers was $74.1 billion as of June 30, 2015, according to a report issued by state Controller Betty Yee last January.

The unfunded liability for pensions promised state workers was $49.6 billion as of June 30, 2015, according to the CalPERS annual valuation of state worker pension plans issued last April.

Meanwhile, retiree health care from private-sector employers is declining. The number of large private firms (200 or more employees) offering any level of retiree health care fell from 66 percent in 1988 to 28 percent in 2013, a Kaiser report said, and this year dropped to 24 percent.

For government employees, retiree health care from employers is not a given, particularly for teachers who, unlike most state workers, do not receive federal Social Security in addition to their state pensions.

A California State Teachers Retirement System survey in 2011-12 found 11 percent of teachers had no employer retiree health care, 49 percent had some retiree premium support until age 65 and Medicare eligibility, and 29 percent had lifetime employer health care support.

“Postretirement premium support varies by hire date and is decreasing,” said the CalSTRS study.

The tentative contract negotiated with SEIU Local 1000 would be, if approved by members, a big step toward the cost-cutting state worker retiree health care reform Brown announced in January last year.

The administration already has new contracts with several smaller unions that include the retiree health care reforms. Prefunding began in 2010 with the Highway Patrol contributing 0.5 percent of pay, now 2 percent until 2018.

One part of Brown’s plan opposed by unions was rejected by the Legislature last year. An optional low-cost health plan with a high deductible would have taken less from the paycheck, but more from the pocket before insurance begins paying medical expenses.

A key part of the plan is negotiating contracts with prefunding that require workers to pay half of the “normal cost” of retiree health care, the estimated cost of retiree health care earned during a year excluding debt from previous years.

Controller Yee said in her January report that fully prefunding retiree health care and cutting the debt from $74.1 billion to $48.4 billion would have cost $3.99 billion last fiscal year, doubling the pay-as-you-go tab.

For new hires, Brown’s plan requires five more years of service to become eligible for retiree health care. Current workers are eligible for 50 percent coverage after 10 years on the job, increasing to 100 percent after 20 years. The new thresholds are 15 and 25 years.

Retiree health care for new hires is capped at the premium support level they received while on the job, eventually ending the “anomaly” of health coverage increasing on retirement, regarded by some as an incentive for early retirement.

While announcing his state worker retiree health care reform last year, Brown pointed to a chart showing that if no action is taken the debt by 2047-48 grows to $300 billion, but under his plan the debt by 2044-45 drops to zero.

“This is a long-term liability that would only get bigger without taking action,” Joe DeAnda, a spokesman for Brown’s Human Resources department said last week, when asked if the retiree health care reform is still on track to cut the debt as planned.

“Starting to prefund retiree health care, along with the other measures we’ve incorporated into labor contracts during the latest round of bargaining, will eliminate this unfunded liability over the next three decades,” he said.

Brown’s plan asked CalPERS to “increase efforts to ensure” retirees eligible for Medicare at age 65 are switching to lower-cost supplemental plans. Most state workers can retire at age 50. But their pension formula, along with annual service credit, continues to increase until age 63 if they stay on the job.

About 69 percent of retirees are in a Medicare supplemental plan, a CalPERS spokeswoman said last week, and 31 percent are in basic health plans, some ineligible for Medicare for a variety of reasons including age.

A Legislative Analyst’s Office report on state worker retirement health benefits in March last year suggested that the Legislature consider offering new hires an alternative to the current plan, perhaps higher pay and contributions to a retiree health insurance plan.

The Analyst said, among other things, the governor’s plan could “require some employees to pay for benefits they will never receive.” Some state workers may leave before serving the 10 or 15 years needed for minimum retiree health care.

Another potential problem, said the Analyst, is that bargaining to begin prefunding retiree health care may require offsetting pay raises, as happened when Brown negotiated pension cuts for new hires four years ago.

A $1 pay raise for the typical state worker increases state costs by about $1.34 due to Social Security, Medicare, and pensions. The Analyst said a dollar-for-dollar offset, or even 75 cents per dollar, could cost the state more than paying all of the prefunding cost without a worker share.

There “arguably is some ambiguity” about whether state worker retiree is a “contractual obligation” protected from cuts, said the Analyst. (The state Supreme Court has agreed to hear an appeal of a ruling that allows cuts in the pension offered at hire.)

The website of a dissident group said the SEIU Local 1000 president, Yvonne Walker, will “continue to misrepresent the facts regarding retiree healthcare costs as not a protected right.”

The tentative contract has an 11.5 percent pay raise (4 percent in 2017, 4 percent in 2018, and 3.5 percent in 2019) and will take 3.5 percent from paychecks for retiree health care (1.2 percent in 2018, 1.1 percent in 2019, and 1.2 percent in 2020).

“When members factor in the increased out-of-pocket expenses of pre-funding retirement healthcare and increased CalPERS medical costs this is not a raise,” said the website of the dissident group, WeAreLocal1000.

After contract negotiations that began in April stalled, the union announced that it would strike on Dec. 5. The agreement with the Brown administration was announced two days before the strike date.

“Our tentative agreement achieves many of the goals we identified as priorities in four areas: improvements in compensation, professional development, working conditions, and health and safety,” Walker said on the SEIU Local 1000 website. “At the same time, we protected the hard-earned rights we won during previous negotiations.”

[divider] [/divider]